Reception and the right to care

Welcoming refugees means designing dignity and belonging: open spaces, porous thresholds, and participatory infrastructures turn temporary shelter into community, promoting justice, relationships, and care as core architectural and urban principles.

Accoglienza e diritto all'assistenza, testo in italiano

Reception as an Act of Care and Justice

A tent city in a remote desert, a row of shipping containers on the urban fringe, or a vacant institutional building hastily converted into refugee housing—each reflects a distinct material and spatial condition of displacement. Despite their differences, these environments stem from a shared architectural and planning paradigm: the logic of emergency response. In both the Global South or Global North, responses to forced migration are frequently governed by the imperatives of speed, containment, and logistical efficiency. In this context, architecture has been reduced to a tool for temporary crisis management, while urban planning has become a practice of spatial control rather than inclusion. Although materially distinct, these emergency accommodations, whether tents, modular units, or converted facilities, often result in spatial configurations of exclusion. Positioned at the periphery or embedded invisibly within the city, they remain disconnected from public services, community networks, and long-term urban visions. Rather than enabling integration, they reinforce the spatial logic of exception, where the notion of care is reduced to minimal shelter provision rather than relational or infrastructural inclusion.

What if we reconsider this premise? Instead of viewing refugee reception as merely a logistical operation, we can consider it both an architectural and ethical practice – a spatial expression of care. Providing shelter is not only about offering a roof and walls; it is also about what those walls communicate. A fenced-off camp on the outskirts signals containment, a holding pattern. Conversely, a thoughtfully designed reception center integrated into the urban fabric can convey a sense of inclusion and respect. In other words, the layout and location of reception spaces reflect how we, as a society, perceive and value the people we host. Every path, public square, courtyard, building, or even room can either reinforce a sense of otherness or nurture relational belonging through care.

This article argues that the design of spaces for refugees is inextricably linked to questions of justice, dignity, and care. When we talk about «reception», we are referring to more than shelter supply; we are defining the initial experience of a new home in a new land. Architecture and urban planning, therefore, become crucial tools for transforming that experience. Can a camp and/or reception facility be planned as a community rather than as a warehouse? Can a city treat incoming refugees not as a problem to be parked on the periphery but as new neighbors to be welcomed within their neighborhoods? By reimagining reception as architecture rooted in care, we shift the narrative from one of an emergency response to one centered on hospitality, belonging, and dignity. This transition from containment to care reveals that the spatial arrangements we create for displaced populations are not neutral; they reflect – and, indeed, enact – our collective values and ethical commitments.

Legacy of emergency architecture and challenges of reception urbanism

The spatial configurations of refugee reception are deeply embedded in the legacy of emergency architecture, an operational paradigm historically grounded in the logics of urgency, exceptionality, and control.1 This legacy has materialized most visibly in the form of refugee camps – sites that are often located in peripheral zones, rapidly assembled, and functionally oriented toward containment rather than integration. In arid borderlands, urban interstices, or institutional buildings repurposed as shelters, the architectural language of emergency frequently prioritizes efficiency and temporality at the expense of spatial justice, dignity, and inclusion.2

Over time, this emergency modality has shaped a reductive understanding of reception as a reactive, temporary measure rather than a proactive, civic infrastructure. The camp, as both an architectural typology and a mode of governance, embodies what Agamben3 describes as a «space of exception» – a zone that hosts without fully admitting, offering protection while simultaneously suspending political and spatial rights. Such spaces often produce a form of protracted liminality, reinforcing spatial segregation, limiting autonomy, and institutionalizing the marginality of the displaced.

In contrast, alternative urban imaginaries have emerged that reconceptualize the process of arrival. Doug Saunders’s notion of the arrival city highlights the potential of transitional urban neighborhoods,4 zones characterized by density, informality, and adaptability, as engines of migrant integration and social mobility. Far from being chaotic or dysfunctional, if supported by equitable planning and policies, these spaces can become generative environments for newcomers to build their livelihoods, identities, and social networks. Building on this, Meeus, Arnaut, and van Heur articulate the concept of arrival infrastructures,5 the socio-material systems that enable newcomers to access housing, education, mobility, and sociality. These infrastructures are not centralized or exclusionary; rather, they are distributed, embedded, and interwoven into the urban fabric. They facilitate connection rather than control, enabling the enactment of care through everyday proximity and interaction. As Meeus et al. observe, «arrival infrastructures are not structures of control, but frameworks of connection – where housing, mobility, and everyday encounters become the architecture of belonging».6

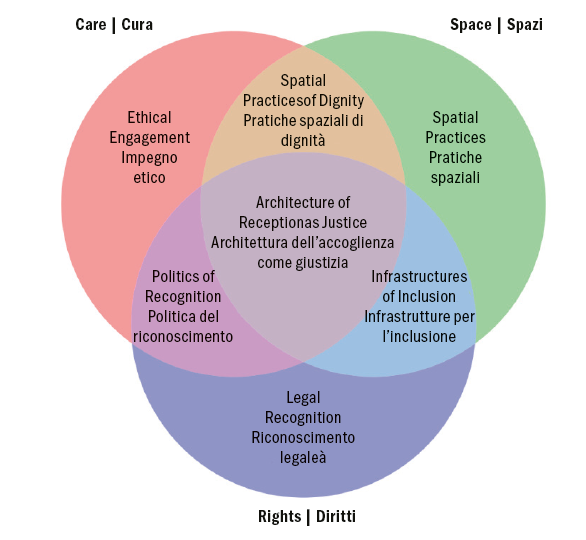

Despite critical efforts to rethink reception, the emergency paradigm continues to dominate. In the Global North, this is reinforced by securitized migration governance, and in the Global South, it is done via donor-driven humanitarian planning. Even in well-resourced urban systems, reception is often treated as a provisional function with minimal investment in long-term, inclusive infrastructure. To move beyond this framework, reception must be reimagined not as a spatial fix but as a dynamic urban process that demands sustained infrastructural support, enabling both stability and mobility. Reception should be embedded in a continuum that bridges emergency accommodation with pathways for civic integration. As figure 1 illustrates, the reception architecture and care. This reorientation calls for a rights-based urbanism,7 in which architecture and planning are instruments of inclusion, materially, socially, and symbolically embedding care within the everyday structures of the city.

Architecture of Care: Spaces of Healing, Empowerment, and Belonging

Reframing reception through the lens of care enables radical rethinking from provisional shelters to civic and affective infrastructures that foster dignity, autonomy, and a sense of belonging. Drawing on the feminist ethics of care,8 care is not merely a personal sentiment but a spatial and political practice—an ongoing, collective responsibility distributed across institutions, bodies, and environments. It demands attentiveness to vulnerability, responsiveness to situated needs, and a commitment to sustaining life in its full complexity. In architectural and urban terms, care entails designing spaces that make room for participation, memory, privacy, and affective expression.

From this perspective, care is inherently spatial.9 In their discussion of the landscape of care, Milligan and Wiles argue that care is not only a moral practice but also a spatial practice that informs how we arrange proximity, enable access, support privacy, and manage visibility and withdrawal. These principles challenge the dominance of logistical functionality in the refugee infrastructure, calling instead for spatial justice10 and the enactment of Lefebvre’s Right to the City,11 understood as the right to co-produce space, not merely inhabit it. When translated into design, the ethic of care materializes across multiple spatial scales and architectural elements. It begins with interior spaces that support healing and well-being; extends to the building’s thresholds, where first encounters with the local community occur; and reaches the surrounding neighborhood or camp, where shared spaces can foster interaction, belonging, and social connection.

Interiority: atmospheres of healing

Care begins within. Interiority is not merely about enclosure; it is also about enabling recovery, autonomy, and a sense of symbolic belonging. In the context of refugee reception, interior design must do more than provide shelter; it must cultivate an atmosphere that heals. Every detail, from the layout of a shared kitchen to the texture of a wall, has the potential to support psychological restoration and foster social cohesion.

The Bidi Bidi Performing Arts Centre in Uganda (fig. 2), designed by Hassell and Arup, exemplifies this sensibility. Conceived as a spatial and cultural intervention in the Yumbe Refugee Settlement, the project reclaims the interior space as a site of memory, identity, and education. Using locally sourced materials; participatory design processes; and layered atmospheres of light, color, and sound, the interiors not only shelter but also dignify. They respond to the rhythms of daily life, offering rooms that are not anonymous but intimately attuned to the cultural practices and rituals of those who inhabit them. Such projects resist the standardized impersonality that too often defines emergency housing. Warm materials such as timber, woven textiles, and acoustically responsive surfaces contribute to an interior language that is sensorial, legible, and humane. These design choices act against the logics of containment by creating spatial vocabularies of familiarity and care.

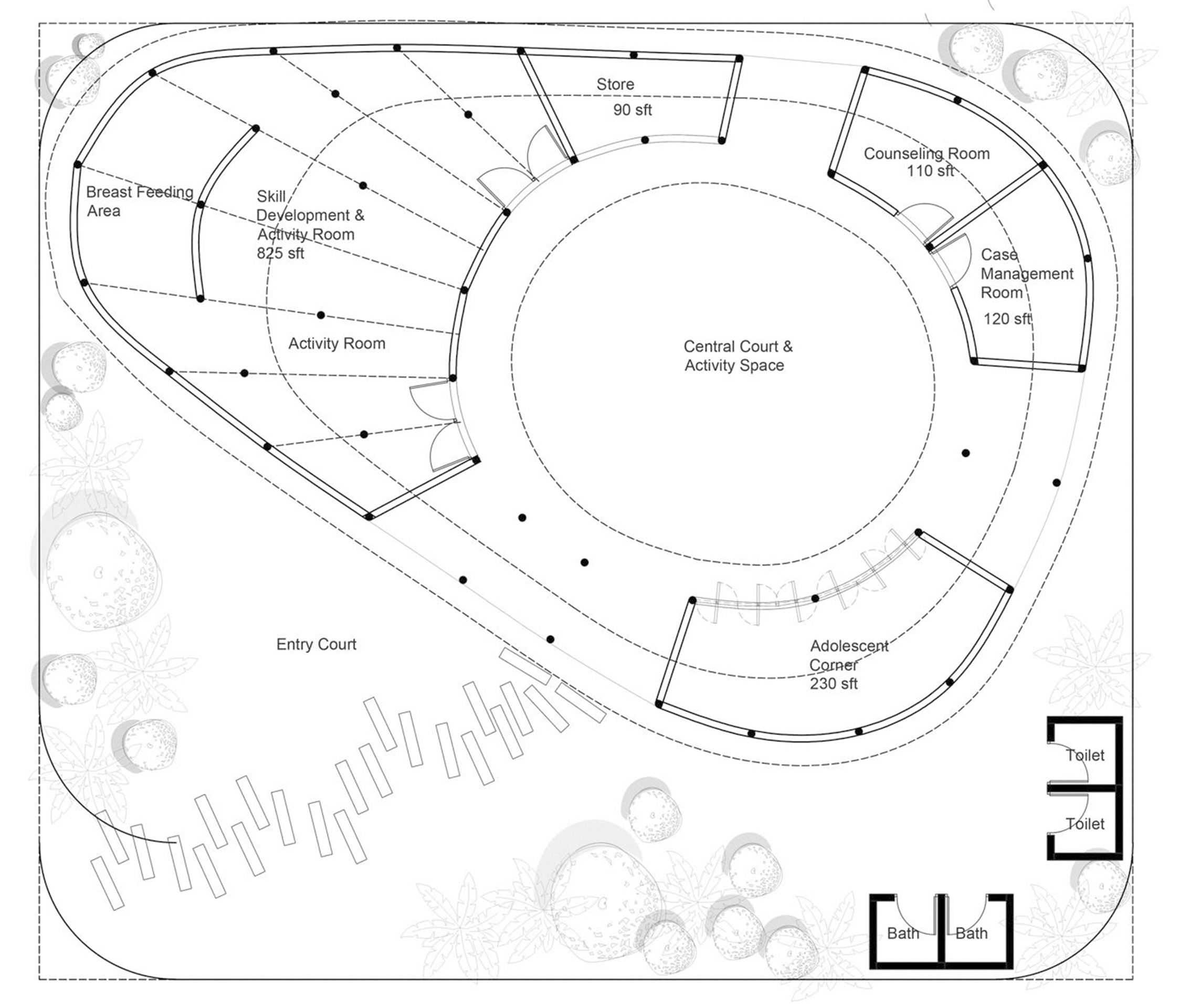

The architecture is most powerful when it intertwines spatial dignity with cultural legibility. As illustrated in the attached plan of the Centre for Displaced Rohingya Women in Bangladesh (fig. 3), privacy is treated not as a luxury but a right. Interior partitions, layered thresholds, and decentralized rooms – such as the Skill Development & Activity Room, Breastfeeding Area, and Counseling Room – allow for a nuanced spectrum of exposure and interaction. These elements offer residents control over how and when they engage with others, enabling solitude without severing connection. Spaces like the Central Court and Adolescent Corner act as flexible gathering areas, supporting both communal activities and informal moments of rest and care.

This ethos of spatial justice is embedded in the project’s material and process. Built with bamboo and local resources, the centre reflects a deep commitment to vernacular resilience and participatory design. Its adaptability – visible in the open, modifiable layouts –ensures responsiveness to both climate and community needs. Signage and symbolic motifs drawn from familiar cultural forms, alongside the circular organization of space, reinforce a sense of orientation and belonging. The architecture is not monumental, but quietly radical: unfinished by design, it empowers its users to continuously reshape it – an act of care in itself.

Exteriority: edges that invite

Care does not stop at the door. In the architecture of reception, the threshold is never merely a line; it is a political and social device that shapes how inclusion, access, and visibility are mediated. A care-full approach to exteriority rethinks boundaries not as defensive perimeters but as interfaces of encounter. Rather than isolating, the edge can invite – semi-public spaces, shared gardens, shaded outdoor rooms, and porous façades generate moments of interaction that blur the divide between host community and the hosted. A striking precedent is the modular refugee learning spaces by Zaha Hadid Architects (fig. 4), designed in collaboration with Education Above All and deployed in displaced communities. Although intended for temporary classrooms, these structures exemplify how edge conditions can be reimagined. The tents form clusters around communal courtyards, using geometry to create sheltered outdoor zones for informal gatherings and shared learning. Their lightweight, high-performance membranes offer transparency and permeability, signaling openness instead of closure. Here, the margin becomes a shared membrane rather than a dividing wall.

These design strategies underscore how spatial legibility and dignity in circulation can be actively cultivated. Pathways are articulated with clarity, and entrances are dimensioned with generosity. Taken together, such calibrated gestures – though modest in appearance – strengthen the permeability between reception spaces and their surroundings, fostering conditions for connection and reciprocity with the wider community. Reception architecture must extend care to the very edges of its footprint. Thresholds, when thoughtfully designed, can foster reciprocity rather than exclusion, enabling everyday rituals of exchange, rest, and welcome. From this perspective, the exterior space is not ancillary but constitutes a critical edge condition, where the continuity of interior care is spatially articulated outward to establish relational ties with the surrounding neighbourhood or urban zone.

From Infrastructure to Inhabitation

Care is not containment; it is cohabitation. Humanitarian shelters often default to infrastructural minimalism; standardized units, modular repetition, and logistical efficiency take precedence over dignity, adaptability, and a sense of belonging. These forms of shelter act more as storage than as homes. However, designing with care means shifting the paradigm from infrastructure-as-storage to architecture-as-inhabitation. Architecture that supports inhabitation offers more than technical performance. It provides a framework for dwelling, memory, and transformation. The Bidi Bidi Performing Arts Centre exemplifies this approach. Developed in collaboration with local artists and residents, the project anchors cultural and social life within a refugee settlement. Its open courtyards and flexible structures invite performances, teaching, and informal gatherings, creating a spatial language that values expression as much as shelter.

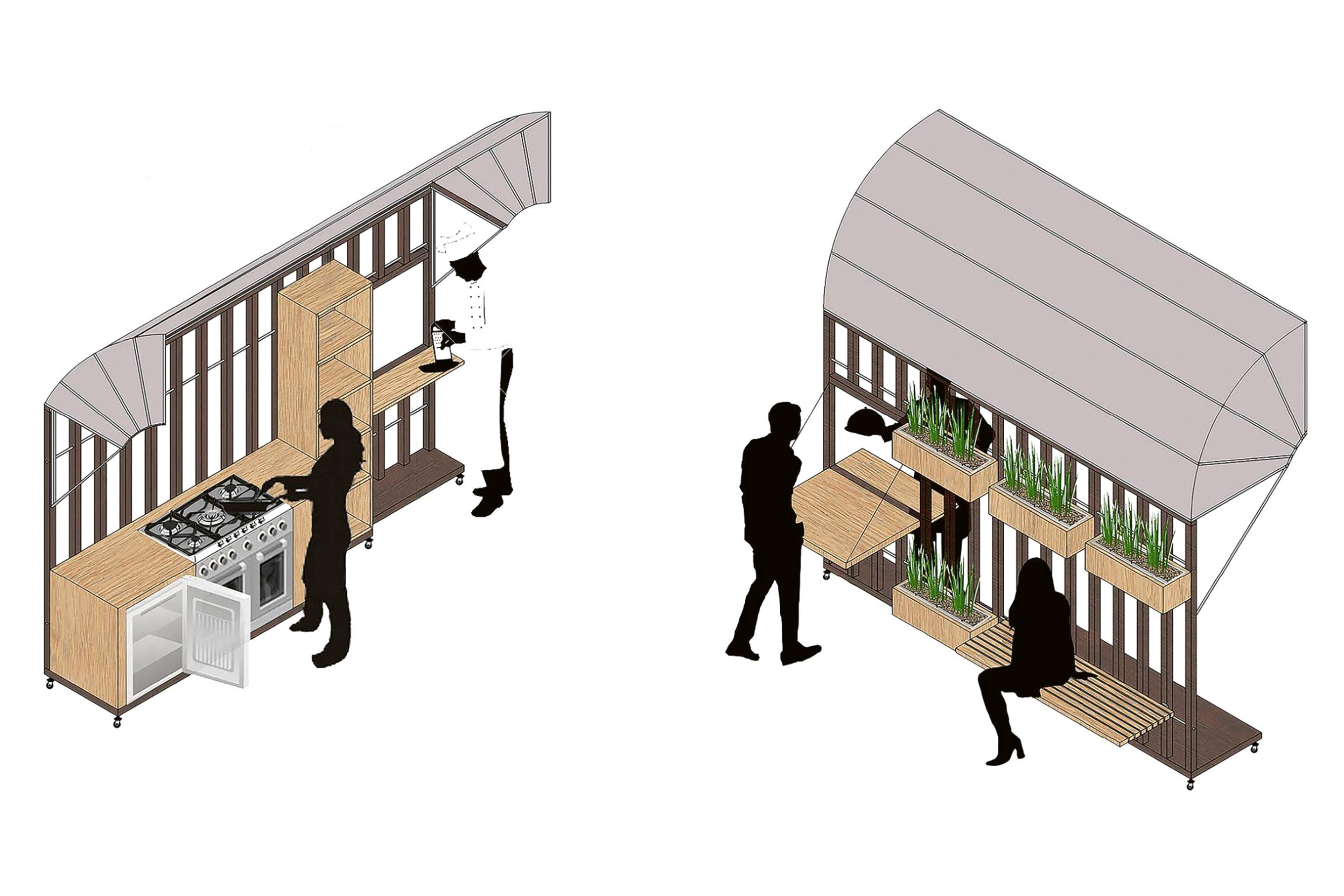

The Portable Kitchen, designed by Soup International (fig. 5), further underscores the value of co-designed, open systems. Created to support displaced populations living in camps and temporary settlements, this movable unit enables communal food preparation, a fundamental yet often overlooked aspect of dignified living. By introducing an architecture of cooking, gathering, and sharing, it restores a daily ritual that nurtures cultural identity, autonomy, and collective care. The kitchen becomes a social core that resists isolation and reinforces community bonds.

These projects challenge the traditional top-down approach to emergency housing. They embrace flexibility, appropriation, and participation. Whether through walls that accommodate personal hooks and photos, kitchens that travel with their users, or classrooms that double as cultural stages, these spaces allow inhabitants to mark, modify, and own their environments. This approach echoes Henri Lefebvre’s call to view inhabitants as co-producers of space. Architecture, then, is not the endpoint but the medium, a scaffold for life to take root. Designing for care requires relinquishing authorship in favor of spatial invitation: an invitation to dwell, narrate, and belong.

Conclusion: Designing Hospitality, Practicing Care

Reception is not a moment but a process, and care is not a gesture but a spatial practice. Across the diverse examples explored, from communal kitchens and cultural courtyards to co-designed interiors and porous thresholds, a common ethic emerges that resists the architecture of control and instead cultivates the architecture of relation. To design for displaced populations is not to design for crisis; it is to design for continuity, cohabitation, and the right to inhabit. In this reframed understanding, care becomes both method and matter: a way of building, listening, and allowing space to be shaped by those who live within it. What is at stake is not only shelter but also the possibility of belonging. It is time to move beyond emergency typologies and toward an architecture that is welcoming, attentive to differences, grounded in dignity, and open to transformation.

A forward-looking approach envisions cities as ecosystems of care, where refugees are not warehoused but housed, not processed but received. Here, reception is not a gateway to marginalization but a point of entry into social, economic, and political life. Such a model is not utopian; it is urgent. In a world of protracted displacement, the city is no longer a backdrop for migration; it is its frontline. Therefore, planning for care is not a soft task; it is an infrastructural one.

Notes

1 M. Agier, Managing the Undesirables: Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Government. Polity Press, Cambridge 2011.

2 R. Sanyal, Urbanizing Refuge: Interrogating Spaces of Displacement, «International Journal of Urban and Regional Research», 38(2) 2014, pp. 558–572.

3 G. Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford University Press, Redwood City 1998.

4 D. Saunders, Arrival City: How the Largest Migration in History Is Reshaping Our World. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, New York 2012.

5 B. Meeus, K. Arnaut, B. van Heur, Migration and the Infrastructural Politics of Urban Arrival, in B. Meeus, K. Arnaut, B. van Heur (Eds.), Arrival Infrastructures: Migration and Urban Social Mobilities, Palgrave Macmillan, London 2019, pp. 1-32.

6 Ibidem, p. 3.

7 H. Lefebvre, Le Droit à la ville, Anthropos, Paris 1968. M. Purcell, Excavating Lefebvre: The Right to the City and Its Urban Politics of the Inhabitant, «GeoJournal», 58(2–3) 2002, pp. 99-108.

8 M. Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of care in technoscience: Assembling neglected things. «Social Studies of Science», 41(1) 2011, pp. 85–106. J. C. Tronto, Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. Routledge 1993.

9 C. Milligan, J. Wiles, Landscapes of care. «Progress in Human Geography», 34(6), Sage 2010, pp. 736-754.

10 E. W. Soja. Seeking Spatial Justice, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2010.

11 H. Lefebvre, Le Droit à la ville, Anthropos, Paris 1968.