«You just flow about»

Together with EM2N and Sergison Bates, noAarchitecten is transforming an enormous former automobile factory and showroom in Brussels to become KANAL – Centre Pompidou, a museum for contemporary art. We asked An Fonteyne (noAarchitecten) about how car ramps lend themselves to human exploration on foot, how art finds a way into a space for car production, and about the persistent fascination of architecture designed to the scale of the automobile.

Dear An Fonteyne, when we talk about the future KANAL, what building are we speaking of?

If you asked anyone in Brussels, still today actually, «Where is the Citroën Garage?», they would think of this building. For many people living in Brussels, especially for architects, this building has always been a fascination. It’s huge. And it was in use as a garage until the competition for KANAL started in 2017. Only then did the cars move out.

The building was a rather particular combination of factory and showroom. How was this originally organized?

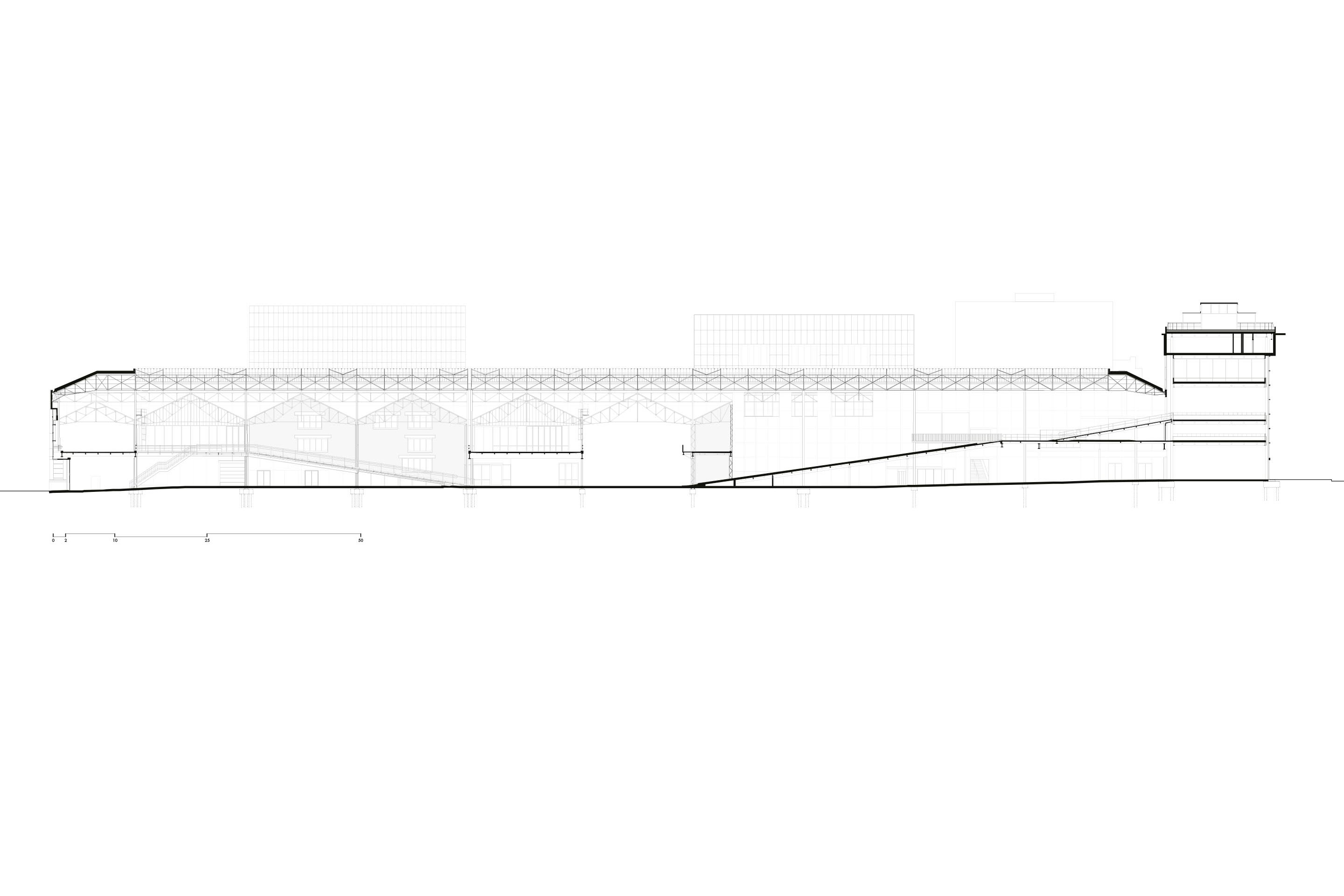

The showroom is by the main road and used to be fully open from street level up. It’s 20 metres high, 75 long, quite big. On old drawings you can see that the bottom windows were guillotine windows. I imagine you would buy your car, step in, and just roll out. And if people went there to have their car repaired, they could in the time of waiting have a haircut or a good coffee. It was a «station-service» to a certain level of elegance – in the beginning, the 1930s. And behind all this is the enormous factory space. On the outside, it features a modernist streamlined façade, on the inside however it is like a 19th-century factory space: lots of small metal pieces assembled to form an amazing whole. One of the many myths of the building is that it was built up in six weeks…

… almost as fast as a Ford Model T!

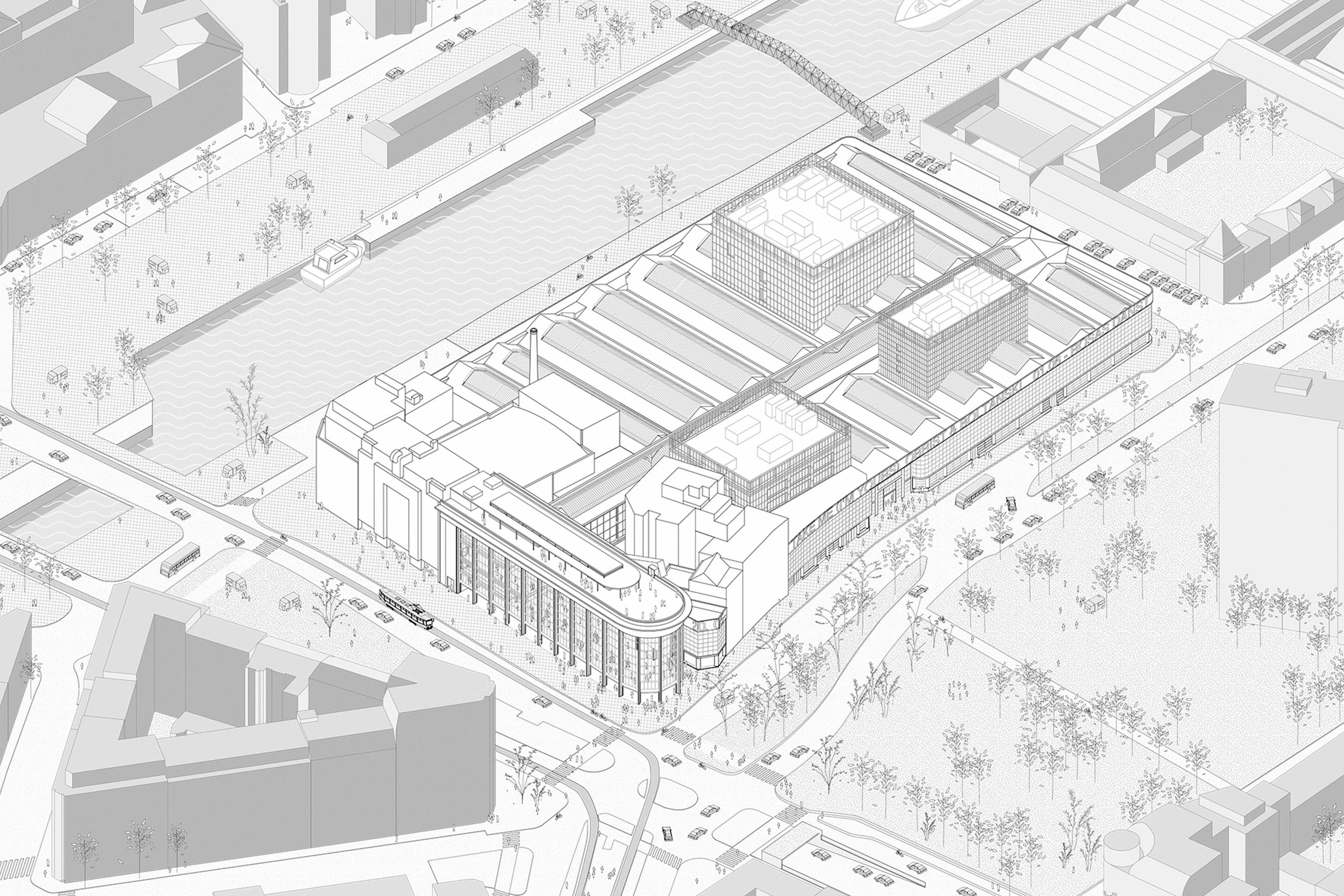

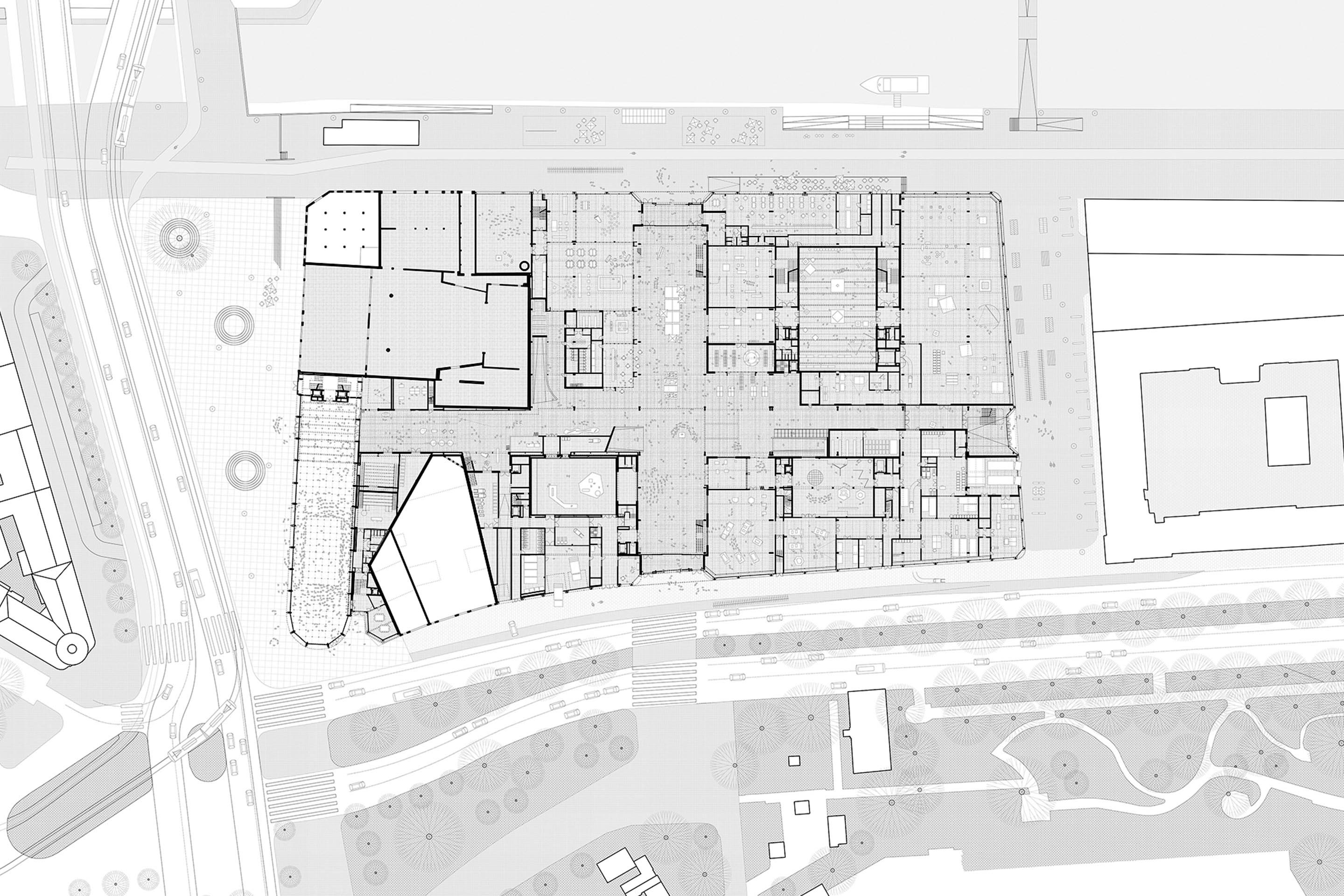

But what is nice is that the central axis or spine connecting the showroom to the factory and repair spaces in the roofline runs 200 metres long, and the other roofs are organized perpendicular to that, giving it a kind of chapel-like atmosphere. Yet a chapel with a footprint of 20.000 square metres.

Eine deutsche Übersetzung des Interviews finden Sie hier: «Da ist nichts museal».

Did you enter the competition straight away with Sergison Bates and EM2N?

Yes. The competition was launched in early 2017, and it was the first big project that Brussels as a public government initiated in a long time. This scale, especially for culture, was unseen. Around 100 teams entered the first phase, and in for the second phase, they selected seven teams, many of which had already a strong relation to the site or to the city. Nearly all teams had local architects in combination with others. We had thought of good company and I had just met Daniel Niggli from EM2N in Zurich in the process of applying for a professorship at the ETH, and visited the Toni- Areal, which is of comparable scale. And we have been working together with Sergison Bates architects on many occasions.

We worked always from Brussels, already in the competition phase. When we won the competition, we decided to set up office in the building itself and worked there for the first two years, which was really nice. In 2018 and 2019, the showroom and garage were opened to the public for one year, called «KANAL Brut», testing it as a museum. Our office and that of our client were in the former Citroën offices. So we could always go out into the building and feel how it worked and look at details. That was a very strong experience. It actually inspired a similar process with ETH students working directly on site.

Did you feel like you were in a space designed for cars?

Oh, totally, yes.

What position did you take to this fascinating yet dinosaur structure as designers?

We said we would trust in what is there. What is interesting when you look at the original sketches of what André Citroën wanted the building to become, you see these very idealized situations where the showroom is shown in a direct connection to what is behind it. In reality, there were buildings in between. But we really liked the idea of the showroom and its necessary support. We decided architecturally we stay with the showroom as a symbol, we don’t add iconic architecture or volumes. In the future, the showroom will become a symbol where people will be drawn in. We take out the floors that had been put in in the 1950s and make a place that is not programmed as such, more a covered square. Where once the cars would roll out, now the audience can just flow in without touching a door, making the threshold as low as possible.

How do you imagine the relation of the building to its context?

The area around the building is called the «croissant pauvre»: a part of Brussels with low income, very dense. This gives you a certain responsibility. So we tried to see how the building would liaise to its direct surroundings. And the building can actually respond to this very well: We decided to keep the strong public figure of the two crossing axes, we keep the ramps so you can go up – ramps which have obviously been designed for cars, but they are very generous and allow people to not have to decide whether you go up a stair – you just flow about.

In the period in which they used it as «KANAL Brut», it worked really well. Kids love to run up and down, it’s not fragile, it’s not museum-like. On the other hand, we also provided less visible routes, vertical shortcuts, for people who prefer to stay in the background, a kind of shadow spaces. Most importantly, we have always believed that KANAL should remain a public interior, with a museum at its heart. We made sure that you are welcome to pass through or stay as long as you wish, and that it’s not the moment you enter that you have to go to the ticket desk and pay. Large parts of the building will actually remain free. We were interested in keeping the art accessible and present.

But certainly climatizing and conditioning a garage for museum use needs interventions?

Yes, of course. However, if you made the whole museum «climatizable», it would be very difficult to keep those façades, to keep that lightness. So we decided to introduce three new volumes in brick which will be climatized: one for the art, one for the CIVA Architecture Foundation, and one for the offices – a fourth one in the block, our neighbour, is the existing Kaaitheater. For the surrounding factory hall however, we together with the client decided to improve the skin but allow the climate to go down to about 16 degrees in winter and up to 28 in summer.

So it would not be the comfort that you expect. The roof will be insulated and the glass which is now single glazing will become vacuum glazing, but we wanted to keep that vastness of space, and the ability of the skin to communicate with its surroundings. It is actually absurd to me that the official requirements to display art mean that you have to climatize a museum space to 21 degrees and 50% humidity. This should be questioned severely. It will cost a lot of money. This kind of climatizing feels like an anachronism. But you need to provide those conditions if you want to borrow art from other institutions.

Does the collection that will be shown there come from the Centre Pompidou in Paris?

For the beginning, yes. They have what they call a «collaboration biodégradable». At the start it’s a very strong collaboration, but after ten years Centre Pompidou will withdraw and KANAL will become independent. As the Centre Pompidou in Paris is closing now for renovation for four years, this may obviously have effects for Brussels. However it’s not a dépendance of Centre Pompidou, not another Metz. An idea that came up later in the design process is to try to make a building that is never finished. Not unfinished and will be finished, but never ever finished. A constant invitation for people to engage with its space, its finishes.

This sounds as if it was inspired by the original Centre Pompidou designed by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, the Beaubourg.

Well, the government wants to reactivate the canal area as an area of production. And for us it was clear that the building should become a site of production, not just consumption. One of our core questions was what kind of exchange between art and the public you could set up in a space that is so big. The «Centquatre» cultural centre in Paris was inspiring in that sense. And Anna Viebrock, the German set designer whom we consulted along the design process, mentioned a poem by John Hejduk which specifies that a house never forgets the sounds that took place in it. She was fascinated by the imagination that when this would no longer be a place for cars, you could still take the risk of being driven over somehow, or that you could hear cars or metal being worked on in the background – she thought this should stay. We still love the idea.

Cars will have a sort of very present absence in the transformed building then.

Of course, people will be walking about in, and using, a space that refers to anything but humans. There was a lot of infrastructure that had to do with car exhaust, and signs reading «démontage» or «tôlerie», the areas where they used to work on cars, but this is all going – it’s already gone actually. It’s a really deep renovation, although we don’t see it as a restoration project. This means there is freedom for interpretation.

Would it otherwise threaten to become kitsch?

I think if you could leave it as it is, it could be perfectly fine. But the moment you touch it, the questions become very clear: do you reenact, interpret, what are the new guiding lines? For example all the paint in the building proved to be poisonous. How to repaint this once wonderful interior? We work together with the artist Sarah Smolders to define a re-set. Within the unfinishedness, it is then up to the users how it will evolve, similar to the garage workers in the past.

What is it that makes this building beautiful? Car factories and repair shops usually weren’t designed to be primarily beautiful.

I think it’s the kind of accident of everything coming together here. It just leads to very nice misunderstandings, the displacement of you being in that space without a car. And also the scale issue. To walk around takes you quite a while. If you built a museum, you would actually make it a lot more compact. And although the characteristics are similar, you are also not in a street, for me. The idea of city-in-a-city does not fully apply. Once you enter there is another way how you behave, engage, other codes – a lot more freedom! You have it a bit in the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern in London. But here it never ends, you can really make your circuit, through small spaces, big spaces.

So did the flow of cars through the building help you organize the flow of people?

Yes. And you could still drive through it if you wanted. It will still function perfectly for the car. What I found interesting in a proposal that came from OMA during the competition: The client had asked for a parking for about 50 cars, and OMA just designated an existing area for that. You want a parking? There is your parking. I liked that. This coexistence of cars and art and people. Now however we are at a moment when the car is everything we do not want anymore. But still trucks and cars can drive in, up and down for deliveries or events. Let’s hope this will happen.

The interview was conducted at ETH Zürich in November 2022.