Designing through the landscape

Dolf Schnebli in Naples

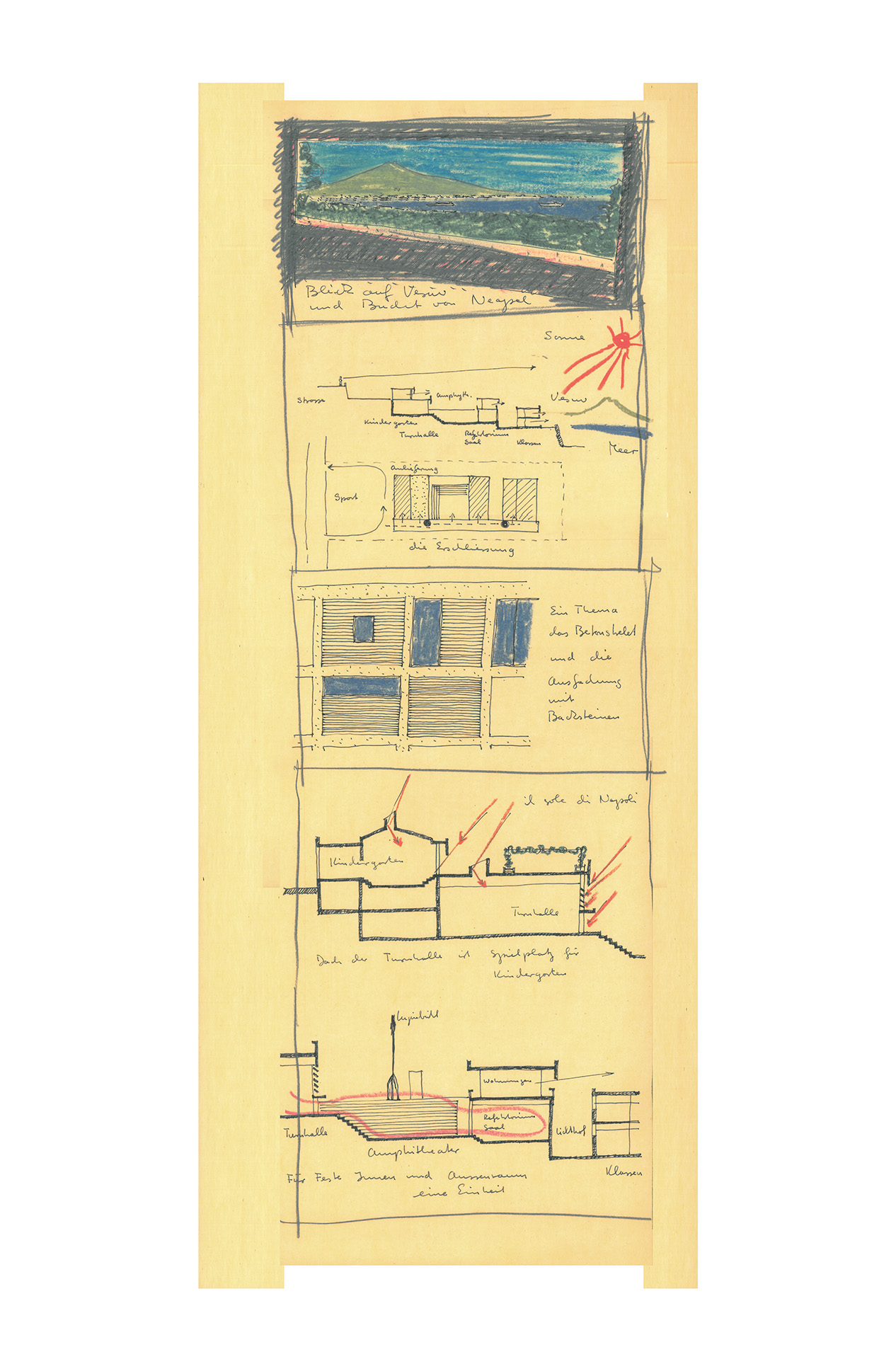

Perched above the Gulf of Naples, Dolf Schnebli’s Swiss School (1964–67) is an architectural landscape: a terraced complex where Mediterranean light, Eastern memories, and pedagogical vision converge. A city within the city, where the school becomes topography and teaching becomes space.

A school with only ten classrooms, designed by a Swiss architect born in Baden in December 1928, and co-financed by the Swiss Confederation1 following an international competition in 1963: what is it doing on the hill ridge connecting Vomero with Posillipo? Clearly, it is a singular complex, built between 1964 and 1967 on an extraordinarily beautiful site to serve as premises of the Swiss School in Naples. In the early 1960s, the oldest school outside Swiss borders, founded in 1839, needed a new home to accommodate its large student body, divided into three levels of education: nursery, primary, and secondary.2

Today, although those days are long gone and the classrooms are now used by pupils of an Italian state school, the complex – acquired by the Municipality of Naples in 1999 and still owned and managed by them – remains a testimony to an architectural experience that links the Swiss-German culture with the Mediterranean and the East.3

The first chapter of this story began with a competition. The jury, composed of Jakob Ott (Director at the Federal Office for Buildings in Bern), Arnoldo Codoni (Inspector at the Federal Office for Buildings in Lugano), Rino Tami and Max Bill, judged Schnebli’s project the best out of the four submitted, 4 rewarding it for its particular attention to the definition of collective spaces, and for proposing the creation of an integral work of art within which architecture would engage in dialogue with art. This special dialogue would take place in continuity with the surrounding landscape.

At the time of the Naples project, Schnebli was thirty-six years old. After studying architecture at ETH Zurich and at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in the Master Class of José Luis Sert with Fumihiko Maki and Roger Montgomery, he established his practice in Agno in 1958, to later open a second office in Zurich. Modernism and, in particular, his fascination with Le Corbusier were fundamental in shaping his architectural vision and so was the long, slow overland journey he took in 1956, at the age of 28, from Venice to India,5 thanks to the Arthur W. Wheelwright Traveling Fellowship awarded annually by the Harvard Graduate School of Design. This formative journey would resonate in each of his subsequent projects and, leafing through the photographs taken during his months of wandering from Italy to India, it is clear how deeply etched every piece of architecture – from the mosques of Istanbul to Chandigarh – remained in Schnebli’s mind, becoming part of his life as an architect and educator.

This deeply influenced the project for Naples, which can be attributed to Schnebli’s first, so-called «epic» phase of production. In this phase, expressive freedom is combined with in-depth spatial research that reinterprets Le Corbusier’s works through the eyes of a traveller. Schnebli recognises the topography of places and natural elements as the immobile driving forces behind the project.

In 1994, Renato De Fusco wrote: «While its private, selective and elitist character shows a considerable social gap with the poor schools and nurseries of Naples, architecturally, it blends into the local environment and landscape better than any other building. Set along the slope between Via Manzoni and Via del Marzano, the complex is designed so as not to obstruct the view of the landscape from the road above. This allows the nature of the place to remain unaltered while ensuring that the gulf can be enjoyed from every classroom and open or closed space».6

Taking the relationship between architecture and landscape, and between interior and exterior, as the key to interpreting the entire complex, we can view the project as either an architectural unit anchored to the slope, or as a sequence of independent «parts», each consisting of a series of volumes and open spaces. These should be analysed individually in terms of their physical and material consistency. Although solely functional to the understanding of the building, such interpretations highlight features of the project that would be difficult to identify without resorting to the anatomical dissection of the intervention, which, given its planimetric and volumetric conformation, is difficult to grasp in its entirety unless explored according to the principle of the promenade architecturale. The building should be interpreted as a topographical fact, deeply dependent on the orographic conditions of the plot on which it stands and in close relation to the landscape it overlooks – first of all Mount Vesuvius, in the background of the gulf. The landscape, in turn, looks back at the building, being the school itself part of the construction of the Posillipo hill.

In 1979, «Rivista Tecnica» published a brief article on two of Schnebli’s unrealised projects, reinterpreting them in terms of landscape Gestaltung, or «the formation – in the sense of «giving form» – and design of nature, i.e. the natural elements that structure the landscape».7 This is certainly the most evident quality of the Naples project, which, although also describable in terms of Schnebli’s research into pedagogical issues through numerous school building projects, is first and foremost a landscape construction machine which looks at Greek theatres and acropolises, Iranian desert villages, Indian fortified palaces to then initiate, in Naples, a transcription process, in an attempt to make the building resonate with the landscape and vice versa.

The project is characterised by an intricate arrangement of volumes in close relation to the topography; Le Corbusier influence, particularly evident in the later works, is in fact declined in relation to the landscape context, drawing on both the local building tradition and the expressive and formal repertoire of Modernism, reinterpreted through the lens of the traditional architecture encountered by Schnebli during his travels in the East. The entire project enhances the characteristics of its location through a process of progressive architectural disappearance in favour of the exceptional Posillipo landscape, which, together with the distant Vesuvius, defines the spatial composition of each part and their sequence. This architectural design of the landscape becomes the project’s central theme.

Alongside the Cantonal Gymnasium in Locarno a few years earlier, the Naples project represents Schnebli’s architectural manifesto in its early years, according to which «architecture and urban planning should be considered integrally, that in fact detail elaboration should refer to the architectonic-urban planning aspect as a whole».8 The building is part of the city, fitting into it by redesigning a portion of the hill with a system of terraces and external paths connecting Via Manzoni with the ancient Via del Marzano: «public schools are fundamental places in the city, so it is the task and duty of architects to consider urban planning not only as a formal issue. […] When I think about schools, the question of «where» kindergartens, primary schools and secondary schools should be built becomes an urban planning problem».9

Furthermore, the school is a city in itself, an architectural landscape conceived in terms of the relationships between its different elements rather than as a single, compact block. For Schnebli, the school is indeed to be understood «as a small city», within which spatial relationships actively influence the child’s growth within the adult community.10 In Naples, the building’s privileged location enhances the relationship between individual volumes, transforming the programme and pedagogical principles according to which functions are organised into an architectural form that depends on the slope. Here, more than in other similar cases, Schnebli designs in section to shape the building’s complexity in relation to the terrain: «The project area slopes steeply towards the south-east. Local regulations did not allow construction to exceed the height of the access road to the north, Via Manzoni. In addition, the splendid view of the Gulf of Naples from this panoramic road had to be preserved. We chose “Slope and Rationality” as the motto for our competition design».11

The building is organised on four terraced levels that slope down towards the sea. It has a complex configuration that De Fusco described as a «a scaled comb scheme, the continuous part of which contains the offices and the «teeth», each of which is a volume intended for a specific function, leave a variously articulated space between them». The element that coordinates this complexity is the central amphitheatre, located halfway up the slope. Its position and spatial characteristics bring together the different parts that make up the project. As in other Schnebli’s projects for school buildings, the amphitheatre courtyard with an asymmetrical cavea represents the place of collective life and the centre around which the entire community gathers. In this case, this concept is reinforced by the decision to embed the steps in the ground. This solution, inspired by the ancient Greek bouleuterion,12 works in harmony with the topography to create a highly introverted open-air room where the horizon disappears into the ground and sky. The amphitheatre is overlooked by the gymnasium, the refectory, the special classrooms, and the laboratories, where the children’s community life and play take place outside the classrooms.

If we take the amphitheatre as a reference point and analyse the longitudinal sections, we can clearly see the sequence of volumes and open spaces which, according to a precise logic of functional aggregation, make up the entire complex.13 In the original functional configuration, the first building upstream housed the two nursery school classrooms, which were directly accessible from the terraced garden. Located in the highest part of the area, they correspond planimetrically to two squares connected by service rooms; each of them is organised on different levels, so as to modulate the children’s perception of the different areas during their daily activities and offer a complex and articulated spatial experience. The roof of the two classrooms is truncated pyramid-shaped with a skylight at the top that allows zenithal lighting in addition to that from the side openings. Just like the large central amphitheatre, the two classrooms of the Schnebli nursery school also draw on the previous work for the school in Locarno and return to the pieces of architecture seen in Turkey and Iran, which, project after project, are transformed into archetypes. Thanks to their high degree of abstraction, as well as the spatial effect they achieve by working with small dimensions, as in the case of classrooms for around twenty pupils, they can be reproduced without too many variations in Switzerland, Naples or the United States. At nursery school level, six stereometric skylights, aligned on the children’s playground terrace, illuminate the gym below, spreading light from above. The staff apartments were located on the upper floor of the volume downstream of the amphitheatre, while the refectory was on the lower level. The third block, directly overlooking the gulf and located to the south-east of a second smaller courtyard, which is more than half a storey lower than the central courtyard, housed the middle school and primary school classrooms, distributed over two floors in groups of four.

While, moving uphill, the longitudinal sections and side elevations reveal the architectural promenade crossing the entire complex with its various branches, the cross-sections fully describe the front of each building, showing how it stands out in the open space. This reveals the volumetric identity and architectural character of all the elements making up the overall sequence. In the tradition of processional routes, each building appears to end inside the open-air room it overlooks. This is particularly evident when standing inside the amphitheatre and looking either north, towards the front of the gymnasium, or south, towards the refectory. It is also apparent from the nursery’s terrace or the embankment above, on which the final downstream volume is situated. The individual transverse fronts are characterised by a monumental layout that enhances spaces for collective life, playing with light and shade to emphasise the relationship between interior and exterior.

The composition and materiality of all the south-east-facing elevations also reveal that the light of the Mediterranean is the undisputed protagonist of the project, as can be seen from the photographs taken on the trip to the East. It is captured and filtered through an articulated system of architectural elements, including canons à lumière, skylights positioned on flat roofs, fixed and movable brise-soleil, and loggias and pergolas arranged along the most exposed fronts. Together with glass walls featuring wooden partitions and perforated brick parapets, these elements create a modulation of the façades with vibrant chiaroscuro effects.

In addition to the combination of different materials – concrete, exposed brick, Douglas fir and Vesuvius lava stone – the project is characterised by the continuous interplay between architectural elements and works of art. These works of art, chosen in agreement with the architect by Remo Rossi, the representative of the Swiss Federal Commission for Fine Arts, are not mere decorative additions, but real spatial counterpoints that emphasise the qualities of the individual interior and exterior spaces. They contribute directly to the pedagogical mandate with which every school building is intrinsically invested.14 The most evident example is Bernhard Luginbühl’s large iron sculpture, Rex (1966), which is in a dominant position in the central courtyard and directs the gaze towards the landscape, communicating a profound sense of fixity and rootedness. Opposite the classrooms, at the secondary entrance on the west side, stands Grand Astre (1966), an aluminum cast sculpture by André Ramseyer. On the large terrace below stands Napoli (1966), a bronze sculpture by Max Weiss. Weiss had previously collaborated with Schnebli on the artistic decoration of the school in Locarno. The brick walls of the refectory were painted by Heinrich Eichmann. The ceramics in the nursery school hall are by Emilio Beretta and represent the only work that remains in situ.15

An integral work of art, which in its complexity may appear excessively rich and articulated to our contemporary eyes, but which demonstrates how true Schnebli’s statement about its uniqueness still is, embodied in the walls and their relationship with the landscape: «If the construction of the Swiss School in Naples was a wonderful experience for us, it is also because in Naples builders and craftsmen still take seriously De Sanctis saying, which can be read on one of the access stairs of our ETH: “Before being engineers, you are men”».16

Notes

1 The land on which the school stands was purchased by the Swiss community in Naples and then ceded to the Swiss Confederation. The Confederation financed the construction with a loan approved by the Swiss Parliament and subsidised the school’s management. The construction company was Neapolitan, while the project manager was Ernst Engeler, a long-standing collaborator of Dolf Schnebli. See the interview with Enrico Von Arx, the last director of the Swiss School by L. Pennati, March 2021. Further information on the history of the Swiss community in Naples and the events surrounding the school can be found. Cfr. E. Von Arx, Istruzione elvetica a Napoli. La scuola svizzera dalle origini ad oggi, in «Arte e storia», 29, 2006, pp. 94-97.

2 On the eve of the Second World War, the school in its previous venue in Piazza Amedeo in Chiaia had 176 pupils, including 30 Swiss, 20 German and 6 pupils of other nationalities. However, the vast majority of pupils were Italian – 120 in total – and so Italian became the language of instruction after the war. In 1967, the building in Via Manzoni was inaugurated. However, at the same time, the number of Swiss pupils was steadily declining. By 1967, they accounted for only 20% of the total, prompting the federal government to withdraw its subsidy. The school subsequently closed in 1984. Cfr. T. Gatani, I rapporti italo-svizzeri attraverso i secoli - Gli svizzeri a Napoli, vol. 5, Federazione colonie libere italiane in Svizzera, Fondazione Ulrico Hoepli, Zurigo 1996, pp. 54-59.

3 A recent, detailed publication sheds light on the complex’s history, from its construction to the present day. It provides an in-depth analysis of the architectural and spatial characteristics of the project. Cfr. A. Como, M.T. Como, I. Forni, L. Smeragliuolo Perrotta, La Scuola Svizzera di Dolf Schnebli, Clean Edizioni, Napoli, 2023.

I would like to thank the authors for the drawings published here to accompany the text.4 Cfr. «Schweizerische Bauzeitung», 13, 28 März 1963, p. 211, in «Wettbewerbe».

5 Cfr. D. Schnebli, One year from Venice to India by the land route: 1956 Photosketches of a slow journey, Niggli, Sulgen 2009.

6 R. De Fusco, Napoli nel Novecento, Electa, Napoli 1994, p. 167.

7 Due progetti sul tema della «Gestaltung» del paesaggio, in «Rivista tecnica», 3-4, 1979, p. 29.

8 Dolf Schnebli citato in| quoted on P. Fumagalli, Der Stoff, aus dem die Häuser sind / Ce dont est fait le bâtiment / What buildings are made of, in «Werk, Bauen + Wohnen», 12, 1990, p. 24.

9 D. Schnebli, La scuola di Locarno, concorso 1959, in «Archi», 3, 2010, p. 21.

10 Cfr. L. Pennati, Architettura che fa scuola. Dolf Schnebli e il caso di Locarno, in «FAMagazine. Ricerche e progetti sull’architettura e la città», 56, 2021, pp. 116-126.

11 Schweizerschule in Neapel, in «Das Werk: Architektur und Kunst», numero speciale | special issue «Schulen», 7, 1968, p. 445.

12 Cfr. I. Forni, Una piccola città nel paesaggio, in La Scuola Svizzera di Dolf Schnebli cit., pp. 116-141.

13 Cfr. A. Como, «Strutture e sequenze di spazi» della Scuola Svizzera di Dolf Schnebli, ivi, pp. 152-199.

14 This was made possible thanks to the Per Cent for Art scheme, which, starting in 1950, required that approximately 1% of the construction cost of public buildings in Switzerland be reserved for artistic interventions.

15 The works of art were removed and relocated elsewhere after the Municipality of Naples acquired the building. Cfr. L. Pennati, (Keine) Kunst am Bau! La scuola svizzera di Napoli di Dolf Schnebli, in corso di pubblicazione.

16 Schweizerschule in Neapel, cit., p. 444.