Building with earth in Côte d’Ivoire

The Residence of the Deputy Chief of Mission in Abidjan

In Abidjan, the Swiss Federal Office for Buildings and Logistics (FOBL) unveils an extraordinary new residence. Between technical, climatic, and cultural constraints, Localarchitecture has designed an inspiring project that highlights earth construction.

“It is the difficult path, but a living wall cannot be designed in an ivory tower.”

Henri Chomette

Diplomatic architecture is a complex equation. It is always subject to a double constraint: between the context of the host country and that of the commissioning country, how should one choose? How can one translate not a so-called “Swiss identity,” but rather a “Swiss way” of perceiving, welcoming, and understanding the spirit of a place and its building culture?

In a country where the modernization of the built environment is historically linked to the colonial project, this becomes particularly complicated1. Even more so in a metropolis that is perpetually under construction—a territory that continues to urbanize and inexorably erase the traces of its past. The response proposed by Localarchitecture lies in collaboration: with the place, the materials, and local know-how.

Critical Regionalism

Abidjan, the economic capital of Côte d’Ivoire, rose to the rank of a modern metropolis in the early years following independence in 1960. Built on an archipelago and bordered by a bay, it became a privileged ground for expression for a handful of modernist architects who were able to adapt their buildings to local culture. This was the case with Henri Chomette, whose Abidjan-based architecture firm designed several of the administrative and banking buildings of the Plateau, the business district whose towers gradually formed the city’s emblematic skyline.

In West Africa, Henri Chomette’s design offices invented a sub-Saharan modernism described as “critical regionalism” before the term even existed: adapting modern principles to a given territory rather than imposing them. His buildings were quickly recognized as a significant heritage, even as a “symbol of unity” by certain leaders such as Senghor in Senegal or Houphouët-Boigny in Côte d’Ivoire. He endowed his buildings with monumental porches, elliptical or diagonal arcades, textured walls, and brick screens that multiply the (cooling) shadows cast on façades.

It is not unreasonable to think that Localarchitecture drew inspiration from certain motifs characteristic of this heritage, and even more from Chomette’s approach to projects. Indeed, to achieve these results, his office worked closely with local companies. “It is only through the slow and sincere integration of workers, craftsmen, and local materials into production teams that regions and countries can be given back the hope of an architecture in which the population recognizes its own values and feels at home”, wrote the architect after twenty years of projects. “Apart from this path, all efforts at identification will remain pastiches.”

Swiss Architects in Abidjan

Our diplomatic story begins in the 2010s, when the Swiss Federal Office for Buildings and Logistics entrusted Localarchitecture with the design of an extension to the Swiss Chancellery in Abidjan, a post-war building of limited architectural quality. The extension was doubled by a generous porch that provides welcome shade for waiting visitors. With its imposing diagonally dancing pillars, the architects laid the foundations of a language.

In 2017, building on this first experience, the Lausanne-based firm won a new competition for the residence of the embassy’s Deputy Chief of Mission (DCM). The FOBL supported the construction of an innovative and sustainable building, intended to be virtuously integrated into the local construction economy.

This time they collaborated with the architectural firm ACA, based in Abidjan. Its director, Francis Sossah, has completed several major works, such as the Palace of Culture, and stands out for his involvement in founding the Abidjan School of Architecture (EAA). Their discussions quickly turned to the preservation of Abidjan’s modern heritage, increasingly threatened by the relentless growth of the metropolis.

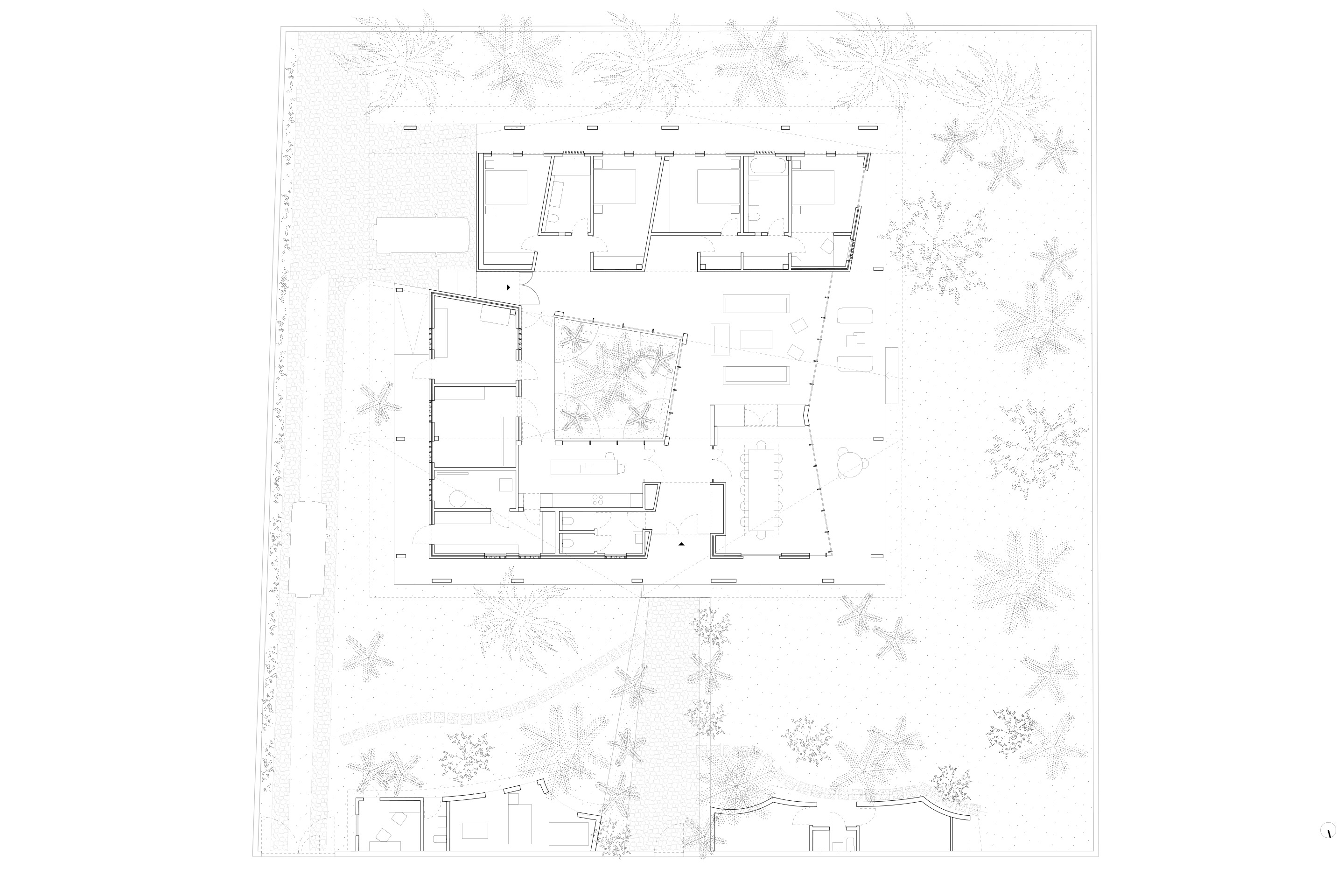

The Two Faces of Diplomacy

The residence of the Deputy Chief of Mission is not a house like any other. It shelters family life, but it is also a place of reception where the discreet stage of daily diplomacy unfolds, with businesspeople and cultural figures who animate the country. Localarchitecture responds to this dual requirement—intimacy and representation—by organizing two zones, public and private, around a glazed patio, and by creating two clearly distinct entrances: one for daily life and one for distinguished guests. The form nevertheless follows a compact typology, a concept that encourages the evacuation of hot air through the courtyard.

The living room opens onto a terrace sheltered by a wide peripheral porch, which takes up the theme developed at the chancellery: dancing pilasters, deliberate asymmetry. Every room opens onto the garden: family spaces on one side, reception rooms on the other.

This duality is reflected even in the construction itself, robust and legible, based on two gestures: a reinforced concrete frame supporting a large, folded roof, and infill made of earth bricks. As soon as the commission was won, Localarchitecture proposed using raw earth extracted nearby.

A Thoughtful Bioclimatic Strategy

In this tropical region, where humidity frequently reaches 80 to 90%, bioclimatic ambitions collide with certain realities: outside air, too saturated with moisture and carrying malaria-bearing mosquitoes, is rarely welcome—certainly not in high-standard buildings. As a result, houses remain closed during the day, and ventilation is most often mechanical and filtered. Localarchitecture quickly realized that the patio alone could not ensure passive air regulation. “It was a false good idea,” explains Antoine Robert-Grandpierre, the partner in charge of the project. The improvement of thermal coefficients had to rely primarily on the performance of the building envelope. Comfort levels would be enhanced by the regular air movement generated by large wooden ceiling fans.

The climatic strategy therefore rests on another lever: the thermal properties of compressed earth blocks (CEB). This material, capable of absorbing moisture and maintaining a drier interior atmosphere, is used to form double walls separated by an air cavity. Through convection, hot air is evacuated, and the material’s performance stabilizes the interior climate.

Earth as Identity

But the compressed earth block is much more than that. Invented after World War II and developed notably at the International Center for Earth Construction in Grenoble (CRAterre), the technique is considered a vector of economic emancipation, particularly by emerging sub-Saharan nations. In Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara held it up as a symbol of autonomy in the 1980s; in the 2000s, architect Diébédo Francis Kéré gave it international exposure. Today, earth construction is enjoying renewed interest, raising hopes for an alternative to the all-concrete development that characterizes the West African coast.

Yet earth bricks still struggle to spread throughout the Abidjan bay, a territory shaped by trade. For thirty years, a CRAterre graduate worked to introduce their benefits to the region. Earth, explains Philippe Romagnolo, remains associated in the collective imagination with rural life and poverty – people do not want it. Yet its thermal efficiency, especially during the rainy season, is gradually winning over an affluent clientele, and the architect is finally observing a certain trickle-down effect: in recent years, his former collaborators have launched their own CEB construction companies.

A Demonstration Construction Site

In the diplomatic context at hand, the choice of raw earth seems particularly appropriate, also because it allows for the transmission of know-how. Localarchitecture entrusted the manufacture of thousands of bricks to the Geneva-based company Terrabloc. One of its partners, Rodrigo Fernandez, traveled to the site in 2023 to train a team of masons, who were discovering CEB. In ten days, the recipes and techniques were studied and practiced intensively until several high-quality mock-ups were produced.

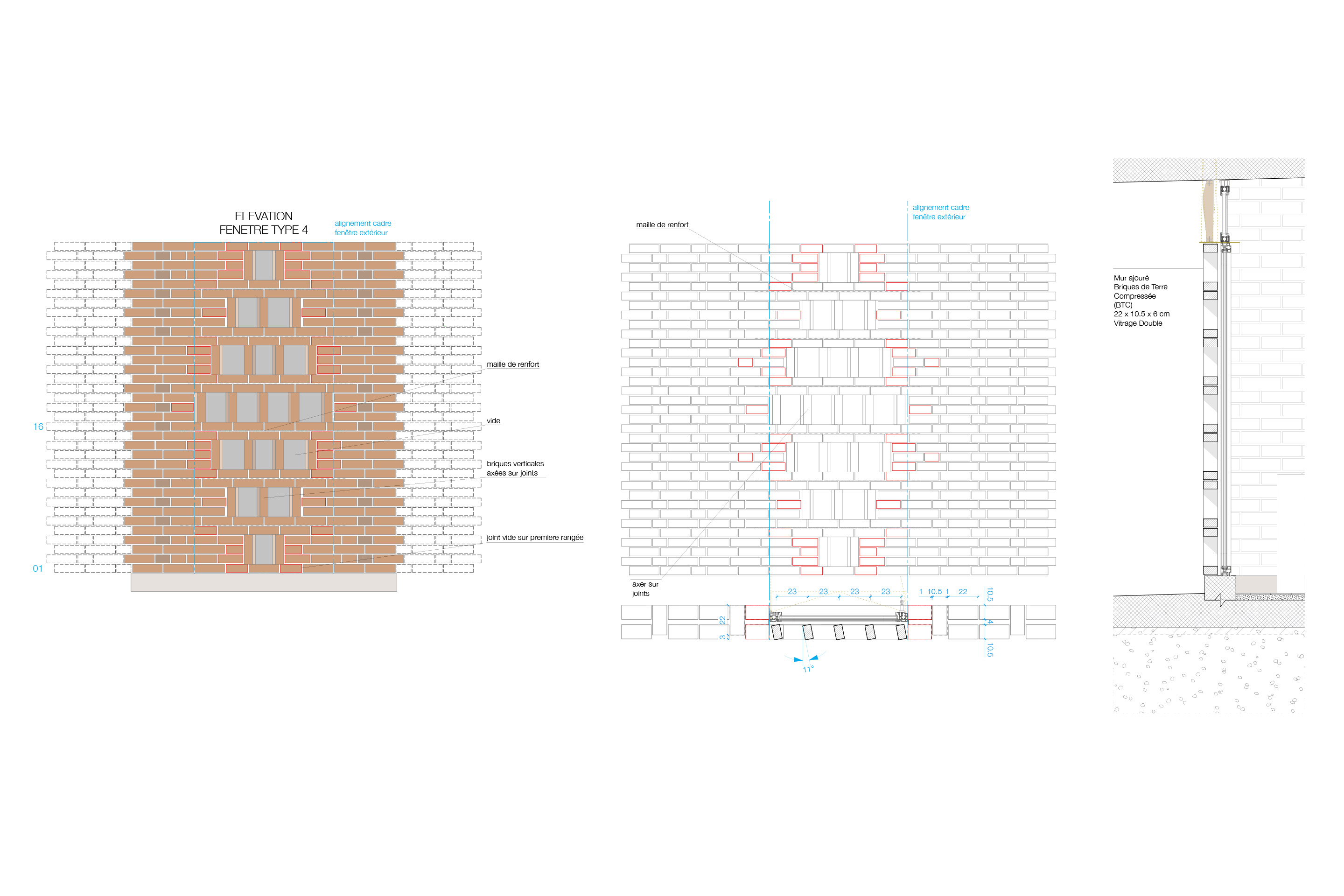

During construction, laterite is extracted near a roadwork site that opened a vein. It is sifted, mixed with cement (8%) and water, then compressed with a hydraulic press (up to 6 MPa). The precious bricks are then carefully stored on pallets and kept protected from moisture—and termites. Storage and especially handling are central issues: laterite bricks are fragile and must be handled with care to avoid defects, even though Localarchitecture allows in its project for an aesthetic of “raw-installed” blocks that reveal their traces of manufacture.

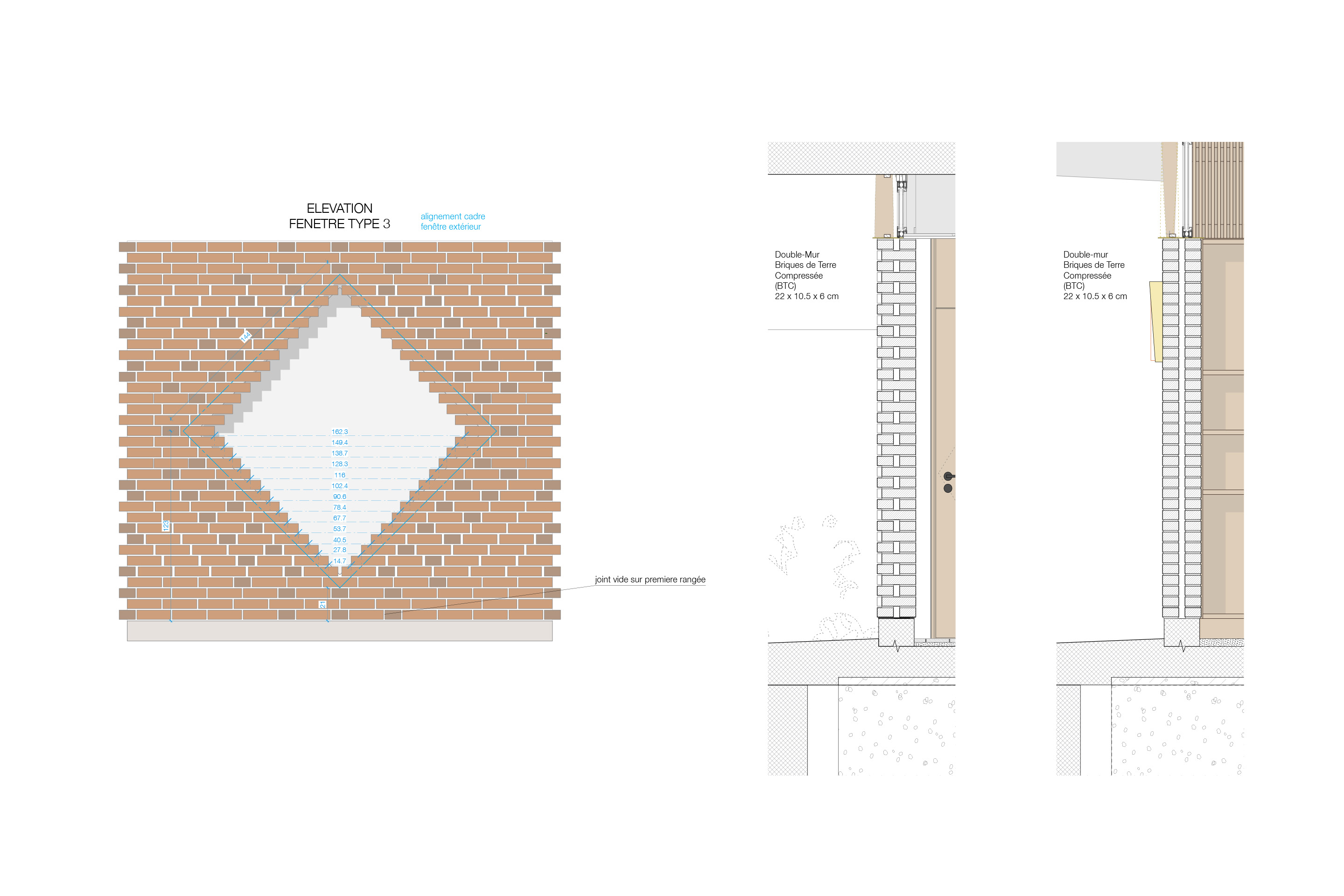

The assembly of the walls is based on a delicate bonding pattern: the double walls are held together not by metal rods but by bricks rotated 90 degrees and set back, forming ornaments on the exterior face. From the entrance onward, the raw earth walls reveal the full aesthetic potential of the material: woven patterns in the reveals, crafted screens around the service rooms, and geometric motifs on the façade. The patterns were developed directly with the newly trained craftsmen and demonstrate their skill.

Import / Export

The first major challenge of this exceptional construction concerns the execution of the concrete work: to build the triangulated roof, the mandated Swiss company sent a handful of workers who lived in Abidjan for nearly a year. Their main working tool, the formwork panels, was delivered by container. Some were reduced to sawdust by termites. Adaptation was necessary.

The pouring operation was made particularly delicate by traffic jams – one of Abidjan’s defining features. Because the concrete came from the outskirts, the mix was kept deliberately very fluid and delivered during off-peak hours, that is, at night. The pouring was carried out at the first light of dawn.

The interior finishes rely exclusively on local resources: Ivorian tropical wood for finishes and furniture, light terrazzo flooring whose changing aggregates recall the color of the bricks. The roof, neither flat nor sloped, features variable heights to manage rainwater, particularly abundant in June. During the rainy season, gargoyles shaped like crocodiles disgorge cascades of water.

Inspiring

Without folklore and without pastiche, the residence of the Deputy Chief of Mission is part of the continuity of an architecture that adapts its solutions – technical and formal – rather than imposing them. With its diamond-shaped patterns and the dancing diagonals of its porch, it could easily be placed within the quest for “asymmetric parallelism” ironically formulated by Senghor in his law on Senegalese architecture. This theme became popular in major West African cities after independence: to express the Africanness of buildings, he proposed seeking an unreasonable order, an irrational rationalism – a poetic, ironic response to an impossible equation. Yet precise rules governed the pillars of the residence, explains Pedro Vieira, project manager: although each pillar is different, they were patiently composed in elevation from the same inverted diagonals, considering the brick patterns in the background.

“A living wall cannot be designed in an ivory tower,” Henri Chomette wrote after decades of construction in Africa. The living walls of the house will undoubtedly inspire discussions—and perhaps vocations. When Rodrigo Fernandez sees the result two years after the introductory training he gave to the local craftsmen, he is impressed by the extraordinary precision of the execution. In the meantime, one mason, passionate about this technique, has launched his own company. In a very concrete way, this diplomatic residence thus fulfills its role as an interface between cultures, techniques, climates, and uses.

Footnotes

1 Especially when one knows that so-called “local identity” in fact results from a long process of mixing and crossbreeding among populations that settled along the coast (Akan, Krou, Mandé, Gour groups, and the sixty ethnic subgroups they comprise), followed by colonists and, later, economic migrants who settled along the bay. In such a context, the pursuit of a supposedly vernacular building tradition can hardly avoid clichés.

2 Léo Noyer Duplaix, « Henri Chomette et l’architecture des lieux de pouvoir en Afrique subsaharienne », In Situ [En ligne], 34 | 2018, mis en ligne le 27 avril 2018, consulté le 10 mai 2023. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/insitu/15897 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/insitu.15897 The quotes from Chomette reproduced here are also taken from this article.

See also the shortened English version “Henri Chomette: Africa as a Terrain of Architectural Freedom,” in Manuel Herz, African Modernism, pp. 270–281.

According to the author, Henri Chomette’s works – shaped by transfers, assimilations, and reinterpretations – can be linked to critical regionalism as identified by Kenneth Frampton. Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” in Hal Foster (ed.), The Anti-Aesthetic. Essays on Postmodern Culture, Port Townsend, WA, Bay Press, 1983.

3 According to his first biographer, Diala Touré, the design office worked as a “harmonic chain” and developed its solutions with local companies, with the aim of freeing itself from dependence on the continent from which construction materials were imported. Diala Touré, Créations architecturales et artistiques en Afrique sub-saharienne, 1948-1995, bureaux d’études Henri Chomette, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2002

4 Henri Chomette, «Digressions à propos de l’intégration des arts et des traditions». Architecture intérieure, octobre-novembre 1977, n° 162

5 Among the references used by Localarchitecture are the patio houses built by the Abidjan-based firm Koffi Diabaté in Assini. These houses operate without air conditioning but benefit from ocean winds due to their immediate proximity to the coast.

6 Armelle Choplin, Matière grise de l’urbain: la vie du ciment en Afrique, Genève, MētisPresses, 2020

Residence of the Deputy Chief of Mission (DCM) of the Swiss Embassy in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

Client: Swiss Federal Office for Buildings and Logistics (FOBL)

Architecture: LOCALARCHITECTURE, Lausanne

Local architect: Architects Consultants and Associates (ACA), Abidjan

Structural engineer: Thomas Jundt Civil Engineers, Geneva

Design: 2017 (competition)

Construction: 2020–2025

La chronique Ambassades suisses est réalisée en partenariat avec l’Office fédéral des constructions et de la logistique (OFCL) – Domaine Construction.