Character and characters of the school

The resonance of tradition

What defines a school’s character today? This essay explores the evolving tradition of school architecture in Ticino and South Tyrol, tracing its roots, tensions, and typological continuities through exemplary projects and interviews with key architects.

Carattere e caratteri della scuola. Il riverbero della tradizione testo in italiano

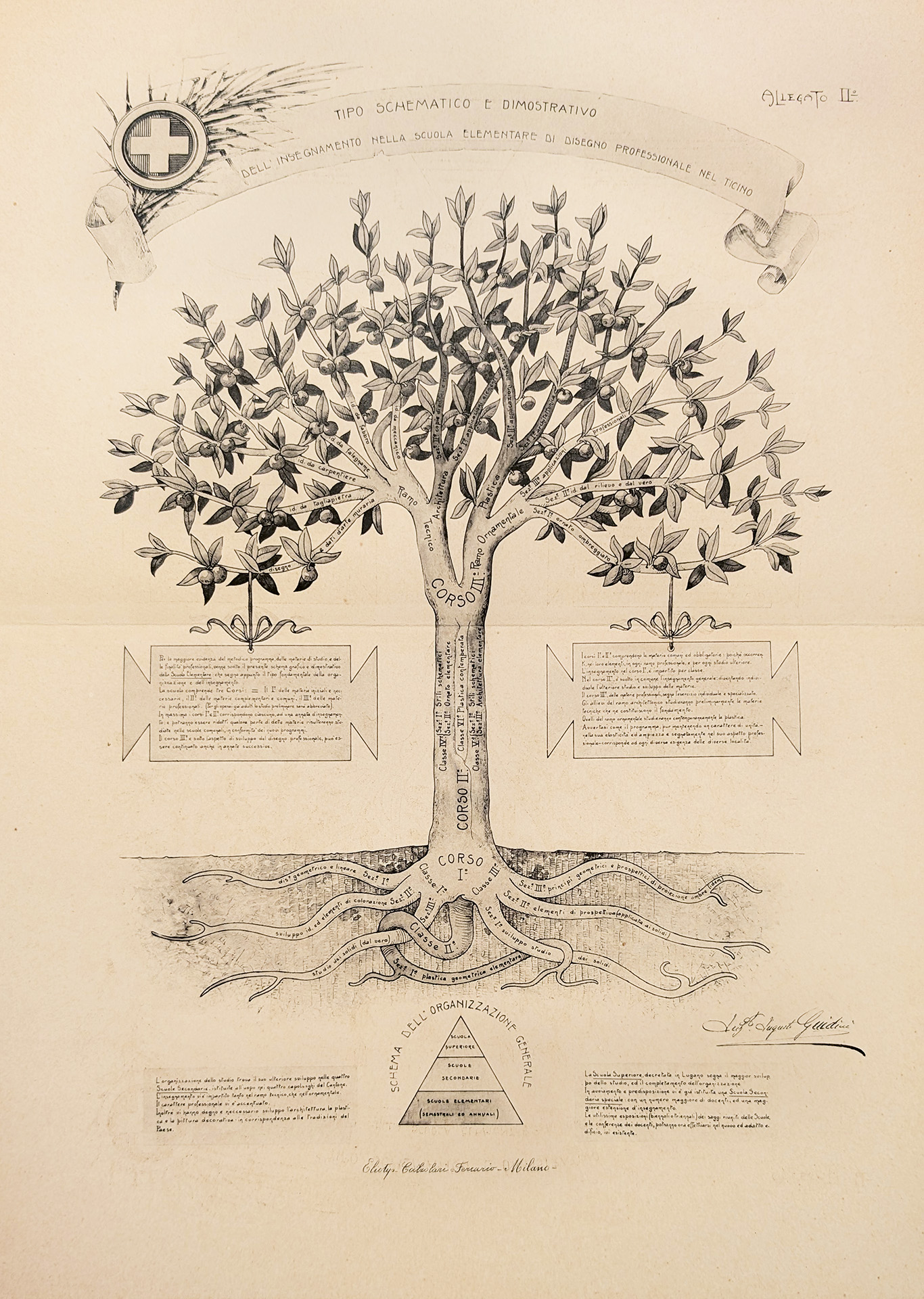

«School architecture in Switzerland, as the translation of a fundamental theme for a people committed to civic progress, has produced – and continues to produce – resolutions of great interest».1 With this clear statement, Giorgio Grassi opened his 1962 article on Swiss school architecture, published in issue no. 266 of «Casabella - Continuità». Through the analysis of two exemplary school projects, the essay demonstrated the coherence between function and form in educational architecture, and stressed that the maturity of historical understanding of a given architectural theme forms the foundation for true experimentation and formal originality.

Rereading Grassi’s words more than half a century later, one may ask whether they still hold true today – whether that continuous process of «translation» has, over time, evolved into a tradition that continues to inform new projects in the background. I believe it has. The numerous publications of recent years dedicated to the heroic phase of Swiss architectural experimentation – particularly in Ticino between the 1960s and 1980s – serve as evidence. That period produced a repertoire «of school buildings that were in many respects exemplary: not only for their remarkable functional, spatial, structural, and constructional quality, but also for their ability to interpret and give form to new and evolving pedagogical demands».2

Yet every tradition raises a fundamental question, as Elémire Zolla reminds us: «Tradition is the transmission of the idea of being in its highest perfection, and thus of a hierarchy among relative and historical beings, based on their degree of proximity to that origin or unity».3 This means that the defining element of a tradition is not to be found in formal resemblance – especially linguistic – but in a shared orientation toward a common destiny. It is this tension that binds works and languages of different times and contexts into a larger opus, one that assumes over time the traits of a distinctive character, articulated through the specificities of each part.

The recent wave of school architecture production and renewal in Ticino offers, both in quantity and quality, a useful lens through which to identify the signs of a possible tradition – one that might be linked to the «a great training ground» of Ticinese architects from the 1960s to 1980s, to borrow Bruno Reichlin’s eloquent expression. If the 2022 issue 2 of Archi, «School Architecture in Ticino»,4 already attempted to trace the points of continuity and discontinuity within this tradition – stretching from the 1950s to more recent works – while noting decisive shifts in its foundational principles and relationship with the broader architectural discourse,5 this issue seeks to explore the vitality of that tradition by comparing it with a geographically analogous one: the case of South Tyrol, a reference point in architectural criticism for its exemplary processes of rethinking the school expressed through architectural language.6

Through a double interview with Sandy Attia and Matteo Scagnol (MoDusArchitects) and Sandra Giraudi (Giraudi Radczuweit Architekten) – two practices with significant experience in educational renewal – the intention is to map out a comparative overview between the school architecture of South Tyrol and that of Canton Ticino. Both regions possess strong identity traits, and architecture appears to clearly express this continuity in the best projects, which are consistently the result of competition-based design processes. In both cases, the last decades have brought major reforms to school regulations, sometimes even revolutionising the very idea of school architecture at every level, by reframing the role of the pedagogical project.

This interview focuses on several foundational aspects of architectural design – the theme, pedagogy, and regulations – as well as key phases of its development into built form: the competition, the site, the construction. The result reveals both resonances and points of tension. From a design experience perspective, both studios underscore the necessity for each project to establish – and, more crucially, to discover from conception through construction – a deep dialogue with the site and the pedagogical theme, which is shaped by the community and articulated by school directors. For both firms, the competition is conceived as a necessary laboratory for original and experimental architectural thinking, while the development phases constitute the ground where this idea must be anchored, through concrete and participatory engagement with other disciplines. Crucially, this occurs with full respect for the limits of each discipline’s remit, as Sandy Attia and educationalist Beate Weiland argue in their now-seminal publication Progettare Scuole, tra pedagogia e architettura: «The more each school builds a pedagogical and didactic profile of its own (…) the more this can be reflected in the architecture that gives it form».7 A shared and renewed interest also emerges in the search for typological specificity, based not on abstraction or generic schemes, but on the singular conditions of each project. This search finds its most meaningful articulations in the relationship between the basic unit of the classroom and the support and circulation spaces – areas now central in educational conceptions and yet still in search of an authentic architectural expression.

On the other hand, Attia and Giraudi – both of whom frequently serve on competition juries and thus have a broad critical view of contemporary production and the current health of architectural practice – highlight a troubling paradox. The abundance of design competitions, driven by the pressure to innovate, seems paradoxically to result in the repetition of the same.8 There is a growing homogenization of design proposals, which tend to flatten under the pressure to efficiently respond to demands often framed in technological, economic, or managerial terms. This tendency undermines the imaginative dimension of architectural meaning and expression – what defines the character of a school. As Sandra Giraudi observes: «The very idea of school, I believe, struggles to renew itself, hiding behind attention to environmental concerns, which, rather than stimulating innovation, are used to justify efficient but standardised and repetitive solutions – solutions with no dialogue with place or community, to the point that I wonder whether they can still be considered architecture conceived for human beings. The point, then, is to reflect on the culture that nourishes the school as a theme, and to ask what defines its renewal».

The projects gathered in these pages instead illustrate the diversity and potential of the various challenges that architects are called to address today. These works share a common need to root themselves in a pre-existing condition of place, where the necessity of renewal becomes an opportunity to rethink the meaning of place in relation to its natural and urban context. All nine projects presented here are grounded in a dialogue with architectural and environmental preexistences – through demolition and reconstruction, extension, or renovation – and are therefore intrinsically linked to a sense of continuity or rupture with the past.

The new school complex in San Vittore by Moro & Moro is the only one built ex novo, and perhaps for this reason, the only one marked by an explicit typological reflection on the role of the school as a «citadel» within a valley territory. This idea is articulated through a plan organized around the interiority of a large central courtyard, composed of three compact, autonomous buildings joined together by porticoes. Other projects are set within existing contexts, seeking to rediscover values that can be brought to light through the addition of the new. In Beier Cabrini’s intervention, a long linear block mediates the elevation changes with the retaining wall of a cemetery, forming the backdrop of the new school garden through a vertical façade – a «habitable wall». A similar compositional strategy is adopted by Bonetti Architetti to restore order and civic presence to neighborhood playing fields embedded in a dense residential fabric. Here, a linear block, this time of a pass-through typology, creates a dual frontage onto the school garden and the adjacent plaza.

The pass-through typology, where classrooms are interspersed with distribution blocks containing stairwells and service spaces, is among the most widely used models to establish a dual relationship in the relatively compact buildings of preschools. In the Lamone school by KSM, a linear pass-through layout redefines the site of the demolished former school, freeing up space for a pedagogical garden and constructing, along the street, an access zone where the school as «filter-building» becomes a design motif: a raised concrete volume of solid and void in lozenge patterns, elevated above a transparent base that opens onto a relational space.

Another category includes extensions to existing schools, where the new interventions establish a direct dialogue with the enduring values of school architecture tradition. The additions by Inches Geleta and Cappelletti Sestito exemplify this, adopting the pavilion layout – functionally and constructively autonomous. The former anchors the pass-through pavilion into a slope, raising the classrooms on a plinth to create a foundational base that ties the whole school to the hillside. The Locarno project, on the other hand, uses the positional logic of the new pavilion to form a backdrop for the 1973 school complex by Dolf Schnebli, itself composed of a two-story pass-through type with recessed porticoes. This new addition acts as both threshold and civic façade.

The dialogue with preexistences becomes even more explicit in the works by Boltas Bianchi in Cadro and Baserga Mozzetti in Manno, reaching a point of material continuity in the construction. In Cadro, the extension of the preschool reclaims the typological and constructive features of the existing courtyard school, reinforcing its layout by extending one wing and reinterpreting its language. The project mirrors the open courtyard scheme of the elementary school on the rear side, shaping a more sheltered garden space for younger children.

Baserga Mozzetti are the authors of two projects – very different in their conditions but bound by a shared sensitivity to reading and enhancing the existing fabric. In the Manno school extension, the new elegant pavilion with a slab roof raised on forked supports reflects and validates the open and experimental character of the 1970 school by Pellegrini, through a symmetrical placement. In Vezia, their renovation becomes a small essay in architectural perception: a project that enhances what already exists, to the point of appearing as though it had always been there.

Thus, the theme of history and the construction of a tradition reveals itself – especially in these specific, seemingly technical cases – as the real key to imagining the new. To borrow the words of Carlo Olmo, a school of architecture – but more generally, any architectural project – should begin by «recovering the value of history, because only in this way can innovation be measured».9 The merely technical question, the mere data, the merely adequate response may not be meaningless – but they are not necessarily meaningful. In the absence of reference points, one may move forward, but without direction. Alfred Roth’s often-cited New Schools10 has had a lasting impact because it offered exemplary cases united by a common spirit. These references are not templates, but tools: they allow us to measure the new, to spark critical confrontation, and to sustain a forward-looking orientation – by relying on them and, at the same time, transgressing them with courage and awareness.

In this sense, rediscovering the recurring and ever-renewing character of school architecture through the qualities of its individual examples might ultimately help us reflect more deeply – on precisely this point?

1. G. Grassi, L’edilizia scolastica in Svizzera e la scuola come esperimento, «Casabella», 266, agosto 1962.

2. M. Iannello, Architettura e pedagogia. Cantone Ticino 1945-1980, «Archi», 2/2022, p. 31.

3. E. Zolla, Che cos’è la tradizione, Adelphi, Milano 1998, p. 134.

4. Architettura scolastica in Ticino, a cura di F. Belloni e G. Zannone Milan, «Archi», 2/2022.

5. «Between the first and second halves of the twentieth century, the assertion of the primacy of modern architecture – its form, language, and aesthetics – found one of its main fields of interest and application in school building design (…). Today, by contrast, there is a growing risk of the opposite tendency: that architectural reasoning in many cases is being subordinated to technical constraints or reduced to a mere transcription of pedagogical trends – an approach that risks overlooking the critical reflection on the relationship between school buildings, the city, and the broader territory». Cfr. F. Belloni, Cosa vuol esser la Scuola? Note sula nuova provincia pedagogica, ivi. p. 24.

6. Dell’argomento si è occupata con continuità la rivista alto atesina | The topic has been consistently covered by the South Tyrolean magazine «Turris Babel». Cfr. Costruire Pedagogie/für Bildung bauen, «Turris Babel», 93, 2013; Zurück in die Schule/Ritorno a scuola, «Turris Babel», n. 119, 2020.

7. B.Weiland, S.Attia, Progettare scuole tra pedagogia e architettura, Guerrini Scientifica, Milano 2015, p. 15.

8. «It may be that today’s hyperactive restlessness, febrile activity, and prevailing agitation are not conducive to thought, and that thought itself – under increasing temporal pressure – ends up merely reproducing the identical. (…) The general pressure of time annihilates whatever deviates or takes an indirect path. In this way, the world grows impoverished in form». Cfr. B-C.Han, Duft De Zeit. Sin philosophischer Essay zur Kunst des Verweilens, 2009. Il profumo del tempo, Vita e Pensiero, Milano 2017. pp. 125-126.

9. A. Roth, The New School / Das Neue Schulhaus / La Nouvelle Ecole, Girsberger, Zürich 1961.

10. C. Olmo, Tornare a Thoreau e Monge, «Archi», 2/2022. pp. 16-17.