No borders

A house at the Black Sea

An interview with Laura Cristea and Raphael Zuber recounts how, on the shores of the Black Sea, building one's own home becomes an existential gesture: a refuge open to the landscape, where intimacy and the world meet in a space in constant transformation.

Testo in italiano al seguente link

The act of building a house has often been a reaction to the confines and limits of a personal situation. Through our work of the last five years, we have posed the question «what is a house for?» to a diverse collection of individuals and discussed the meaningful spaces that form one’s personal memory of experience. It is through this work, that over time, the common struggle for housing, that nearly all of us face, often relates through different yet common means.1

Laura Cristea e Raphael Zuber are two architects who, in their work, transcend borders, cultures and norms. We have admittedly spoken to them before, coincidently both at the beginning and at the very end of their recent endeavour to build a house for themselves on the shores of the Black Sea in southern Romania.

The act of dwelling, of building houses, of taking land, of marking ownership or occupying place, lies at the very core of architecture; this offense, or more common act, is made even more explicit when the project is for a holiday house, a shelter of escape in what is often a faraway place. In this case, the house is very much thought from a centre, the imperceivable centre of a private life that in the moments of occupation, reveals itself to a public realm and natural environment with an uncommon openness.

Riccardo Amarri, Matthew Bailey, Załuska Mateusz (ABM): Why build a house in Romania?

Laura Cristea, Raphael Zuber (CZ): We believe building your own house is the best thing one can do. Building is designing life, and when you build your own house this becomes so very obvious. You are forced to make decisions and there are no excuses. For a long time, we had dreamt of doing that and searched for a piece of land somewhere close to open water, where we could also swim. Other important criteria were that it should not be more than three hours away from an international airport and it should be financially and practically realistic to build. So eventually, when a bit by accident, we found this plot at the Black Sea and got the chance to buy it we didn’t hesitate, even though it was not certain if one would ever be able to build anything on it. When we bought it, it was still agricultural land.

ABM: Did you ever consider building something else there?

CZ: The area is probably one of the last buildable areas along the Romanian coast and we are among the first ones to build there. The most obvious and financially reasonable thing to do would have been to build a small hotel or a pension. However, we didn’t want to commercialise the plot and we like the idea that, in future, we will have our own private world within what will become probably quite a chaotically developed area. There is nothing romantic about it.

ABM: How does the house relate to the plot?

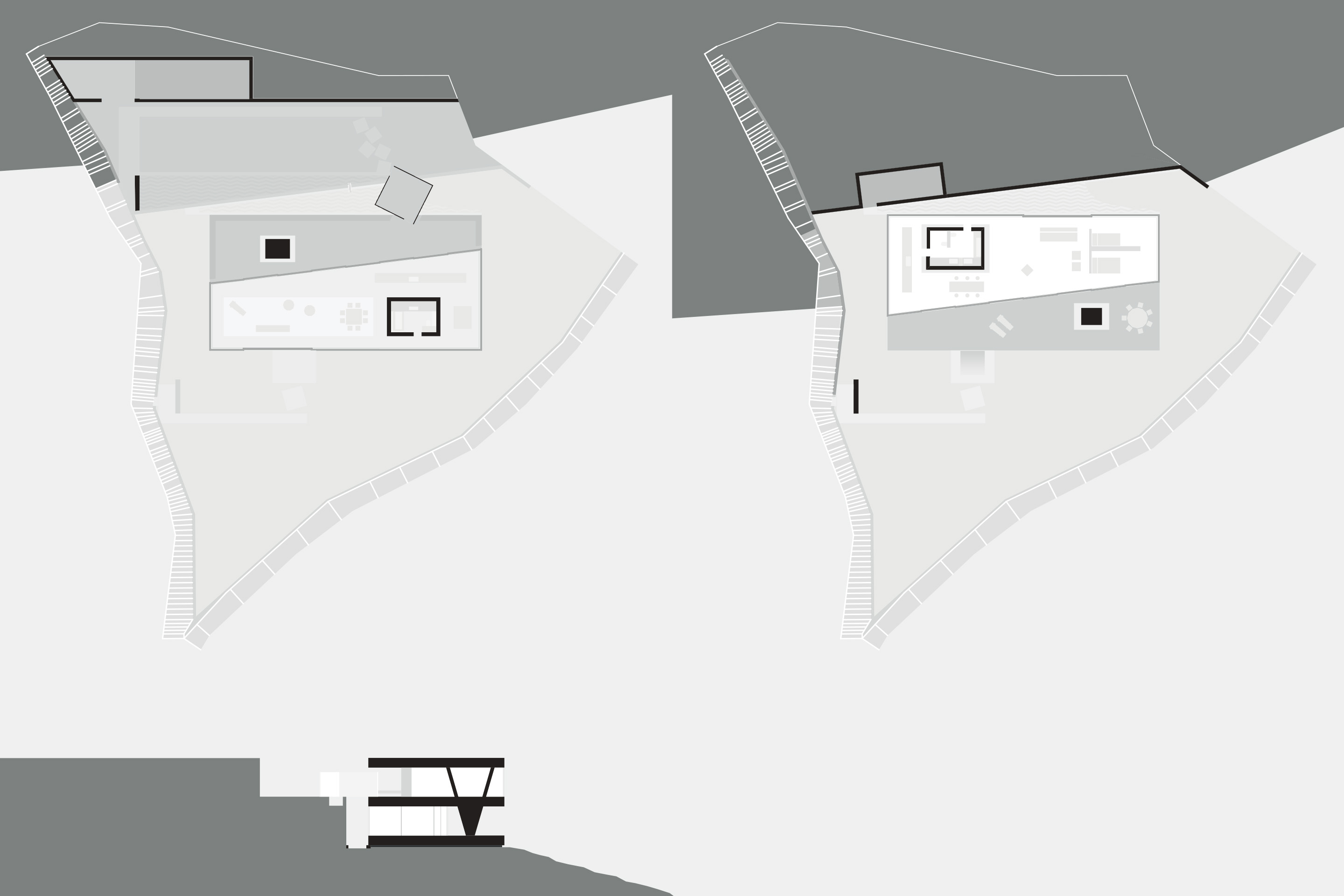

CZ: From the beginning, we were very aware that over time our house would be joined by many neighbours, and even since we started construction, the area has already begun to fill up. That is why instinctively we started to think of a courtyard, of a house with its own internal relations, where whatever happened around us would not affect our lives and in turn our own habits would not interfere with others.

After a while we liked less the idea of closing ourselves away and began considering everything around as nature; its beauty, its ugliness and its transformation in time. Whether it is another building or vegetation, it’s all part of a landscape that just grows, and we cannot control it. From then on, we started to think of how to be part of this reality, of this endless space in constant transformation and of how to feel comfortable in it and to «make it ours».

ABM: How did climate influence your understanding?

CZ: Summers are hot and dry; temperatures easily exceed 35°C. In winter temperature can go down to minus five degrees and it’s very humid with almost horizontal rain or snow fall. During the day there is constant wind that can be quite strong and often changing in direction. In the evening though, the wind usually calms down and it gets totally quiet, also acoustically. From the very beginning, we wanted to build a house where we could live outside, and therefore, the platforms, walls and roofs that it is composed of, are arranged in such a way to always provide a sheltered area, no matter the weather condition.

ABM: To be indifferent and in acceptance of all that comes around, is something that is not common in a time when often a fence or wall is used to strongly define and keep private unseen space. Where does this conviction come from?

CZ: As mentioned before, we started with thinking about a courtyard. But through experiencing other houses, also houses that we admire very much, it became clear to us that we did not want to build an enclosure, it was not something we felt comfortable with. And so, over time, it became a house which is almost not there. It is rather a structure in the landscape, which one lives around, moving between contradictory states.

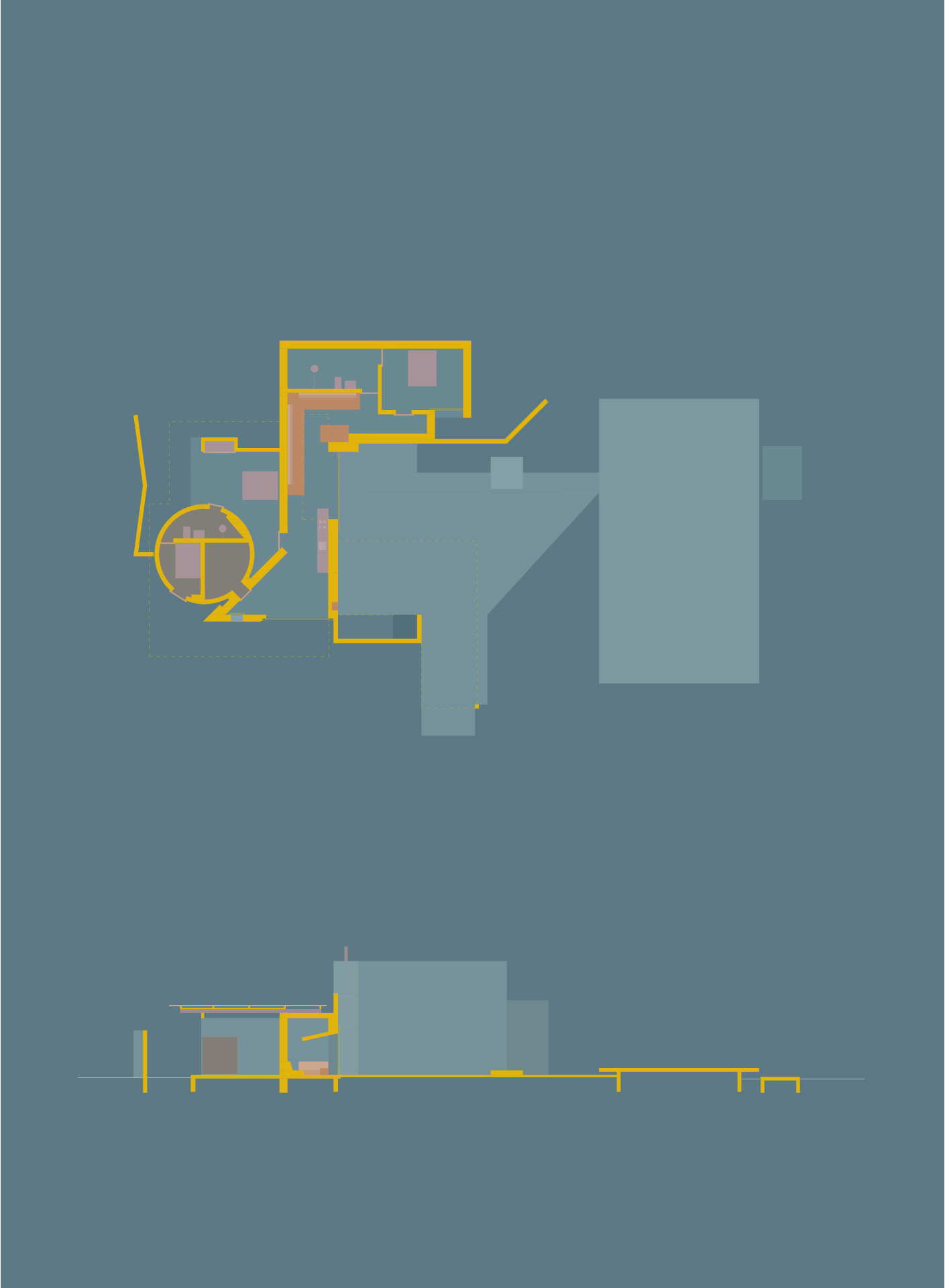

The indoor bedroom and the shower room are the only rectangular rooms in plan. They are the only spaces with a clearly defined border and an almost cave-like feeling. The more one moves away from there, the less defined the borders are. Spaces or sequences of spaces start to overlap, to blur together and to be more exposed in character, culminating with the open platform along the street. All this, including the constantly changing surroundings, becomes one single space disappearing in endlessness.

ABM: We find this fascinating, it is more a shifting landscape of elements, of uses – the revealing of private and public actions – how do you see it?

CZ: Moving around in this house is not moving from room to room. The act of moving around is more abstract and essential; it makes you remember conditions left behind; it makes you understand and feel that you are always part of a much bigger space than the space you physically perceive around yourself.

ABM: In a sense the house is never truly perceivable – a sequence – and never an object…

CZ: Right. If you see the house from one side, it is impossible to tell what it looks like from the other. Moving just a little, the space around you can radically change in character - you can for example suddenly feel more private, or completely exposed or even feel protected and observe, and so on. Consequently, the continuity of space and all the different experiences therein make the house feel very big.

We don’t want to be detached from public life, from society, from nature or from space itself - we understand everything as one thing and we want to feel strongly connected to it.

ABM: Does this connection have an origin from where you modulate what is private and what is public?

CZ: We consider having areas of different, even opposing degrees of intimacy, not only rich, but existential. The indoor sleeping room is the only room where you precisely feel a geometrical centre (the shower room has a top light offset from centre). This makes it the most detached, the most self-focused and thus the most private room of the house. From there, this one space gradually develops, getting increasingly more exposed in character. We imagine it great to sit on the elevated platform on a warm summer night, after the wind has stopped and in complete darkness.

ABM: How does daily life unfold in such a space?

CZ: This is something we also wonder. Certain areas of the space are quite specific. For example, where the space turns dark around the corner, it naturally invites for sleeping, or where the ceiling is lower in the long corridor-like area, a more intimate sitting place around the fire is created. But we hope it will be a place where one moves according to season, weather and the people around. There will always be an area protected from wind, depending from which direction it blows. Or there will always be an area protected from sun, depending on daytime. The transitions of this space provide highly differentiated areas, and there will always be a place where one feels comfortable or even better, grand. We believe that being exposed to these changing conditions and to always being able to react on them and to accommodate ourselves elegantly will create a great comfort and mental freedom.

ABM: How many people can be there – is it a place for a big party?

CZ: We always wanted it to be a place where anything is possible. One should feel good alone or in two or with many people, even with strangers. And yes, we are planning to have parties, perhaps even with a band playing there on the platform, next to the sea, under the moon...!

ABM: Can you explain a little the situation?

CZ: The plot is on a horizontal plateau of agricultural land, elevated about 10 m above sea level. It lies behind an un-paved dirt road that follows the back of the beach, which is a very wide and wild place – belonging to a natural preservation area. Along this street, like a stage, there is a platform of 9 x 16 m, raised from the ground by 80 cm. Behind it, like a backstage, there is the main outdoor area, surrounded by three walls of different heights and partially covered by an inclined roof. Behind these walls is the heated area, from where one can reach the outside sleeping place on the other side of the house and in doing so, loose relation to the sea. Looking out to the beach, the platform sets both a horizon and datum in the landscape.

ABM: When working on the project, as architects, how did you develop and control these spatial progressions?

CZ: Basically, we were thinking about what we like, and at the same time of course also about what we don’t like. We were discussing about how we ideally imagine a day, about how we like to get up in the morning, how we like to sit comfortably and have a drink, how we like to have a shower after returning from the sea, how we like to cook, how we like to go to swim and to what we wanted to come back to etc.

But we were also thinking about how we would like to do all this on a hot summer day, when not even in the night it really cools down, or on a stormy winter day in a frozen landscape, alone or with guests. We were imagining whether we would prefer to sit under a roof or not, whether this roof should be high or low, horizontal or inclined. Or whether we would like to have a view on something or rather prefer to just know that we are looking in direction of that something... We simply thought about everything we would like to do there and how we would like to do that, and of course all of that always related to each other. Actually this is how we always work, but with your own house everything is more existential.

Together, all these experiences and moments do not have an overall imposed form, and consequently, the house is an addition of single elements. To bring them together into an interdependent unit we mainly worked with plan drawings, to control the general layout and the order of things and a 3D model in order to help us to imagine space. Before starting construction we made a cardboard model to explain to the builder what he would have to build, but we are still not actually sure if that was helpful...

ABM: Please, could you speak about the materiality of the house and how it is constructed?

CZ: Our house is among the very few exposed concrete buildings built in the country. In Romania, construction is often based around the act of bricolage and the combination of different materials and structural systems. We wanted to do something very solid – a structure that would last; a house that one can clean with the water hose.

After almost one year of searching we found a builder who was excited to take on the challenge and collaborate with us. Most of the work was done by hand, including digging foundations and setting up scaffolding. We were able to get some standard Doka formwork panels, and after periods of experimentation and invention at each pouring stage, the concrete turned out very nice. For the heated part of the house, we used insulating bricks, which we combined with the necessary conventional structural concrete parts, so that together they appear and work as one mineral unity. Finally, the exposed bricks are thickly brushed with plaster and the whole building is stained with a unifying light blue wash. This colour tone is extremely sensitive to light and depending on the sun exposure, each element of the building might appear very differently. The appearance of the house is constantly changing and stays in our heads as a dematerialised structure.

We very much like to swim in the sea or to be at the beach and to look back at the house blurring with the sky; and under the hot sun, the light blue tint makes for a pleasantly cool atmosphere.

- Place Shore of the Black Sea (RO)

- Client Laura Cristea, Raphael Zuber

- Architecture Laura Cristea, Bucharest + Raphael Zuber, Chur (Pelinu Projects SRL)

- Collaborators Denisa Balaj, Jonas Domeisen, Edyta Filipczak, Yohei Fujita, Magda Juravlea, P+P

- Civil engineering Ionuț Negreanu (Expvibra SRL)

- MEP Engineering Costin Chițu

- Contractor Cataleya Building SRL

- Photography Laura Cristea + Raphael Zuber, Mihai Rotaru

- Timeline 2018-2025

Riccardo Amarri, Matthew Bailey, Mateusz Załuska, «what is a house for... stage of public performance, element of society, territorial organism, place of unconsciousness and vulnerability, challenge to comfort, a device to awaken your conscious, collider of contradictions, host of inner conflicts, act of resistance, portal of memory and threshold to infinity, of blurred limits» (Lecture, ETHZ, May 17, 2023).

To learn more about the research project by Riccardo Amarri, Matthew Bailey and Mateusz Załuska, https://whatisahousefor.com/