Domestic and urban in the single-family house in Switzerland

The essay traces the recent evolution of the single-family home, amid critical reinterpretations, social changes and new experiments. An updated picture that shows how, despite the contemporary debate favouring collective living, the single-family home remains an essential laboratory for design.

Testo in italiano al seguente link

A paradigm shift

Compared with other typological themes related to dwelling that the magazine has examined over the past years – the design of public space,1 collective housing2 and the relationship between solids and voids in the cities of Canton Ticino3 – the single-family house today seems to attract less interest in Swiss architectural discourse.

Although not numerous, some recent publications allow us to trace the most significant research trajectories in this field. In the 2010 survey Ville in Svizzera, the most comprehensive on this topic, Mercedes Daguerre highlighted how the theme of the house – from the chalet to the residential buildings of the 1920s and 1930s, and then of the 1960s and 1970s – was at that time still a highly fertile field for experimentation. The seventeen contemporary cases examined – seven in Canton Ticino, four in Canton Zurich, two in Canton Lucerne, and one each in the Cantons of Aargau, Jura, Thurgau, and Vaud – demonstrate the renewed attention of those years toward landscape components, inspired by the archetypal elements of mountains, lakes, and vegetation, and simultaneously toward artistic expressions that introduce into the design process themes linked to perception, movement, and temporality.4

Prior to this analysis, the collection published in Ville in Italia e Canton Ticino by Paola Gallo and Silvio San Pietro had shown – through the houses of Michele Arnaboldi and Franco and Paolo Moro – a questioning of past linguistic and ideological dogmas, while simultaneously exploring new «interior landscapes» where small «private universes» desired by clients, or, in a more autobiographical approach, fragments of memory collected by designers, could be articulated.5

The most recent investigation, Case in Ticino by Tiziano De Venuto,6 shifted attention back to the relationship between architecture and construction through a journey among residential buildings in Carabietta (2010) by Stefano Moor, Bellinzona (2012) by Guidotti Architects, Gordola (2012) by Baserga Mozzetti, and Locarno (2018) by Inches Geleta, focusing on interpretative categories linked to modes of interaction between form and structure such as lifting and suspending.

Compared with contemporary surveys, readings of certain seminal works of twentieth-century Swiss architecture appear more frequent, even up to the present. The monograph dedicated to the Casa a Paros (1992–1998) by Silvia Gmür and Livio Vacchini7 examines the work’s characteristics while tracing its cultural imaginary. In his account, Roberto Masiero emphasizes the building’s figurative essentiality, describing it as «nothing more than a large terrace-platform protected by two giant walls», designed primarily in relation to natural light, and, in homage to Le Corbusier’s Modulor, dimensioned horizontally and vertically based on the module defined by the thickness of the wall and slab.

Similarly, the study by Davide Fornari, Giacinta Jean, and Roberta Martinis on Carlo Scarpa’s Casa Zentner in Zurich (1963–1969) analyzes the work through its inspirational elements, reflecting on the role of the client Savina Zentner, the succession of project versions, and the description of a creative process in which the building emerges not as a mere nostalgic exercise but as the composition of an «atlas of figures» representing Savina’s identity.8

Attention to the relationship between client and project is also emphasized in the publication dedicated to the Casa a Brusino Arsizio (1959–1960), realized by Flora Ruchat-Roncati together with her father, engineer Giuseppe Roncati. In his essay Satisfaction de l’esprit, Nicola Navone highlights how the house was conceived as a narrative about her personal history, cultural references, and relationship with the figure of the father – the real Giuseppe Roncati, from whom she sought to emancipate herself on this occasion, and the «noble» Le Corbusier, whose influence she aimed to underline.9

Reviving a theme

The editorial team of Archi devoted consistent attention to the single-family house until 2015.

Issue 1 of 2013 analyzed the relationship between building and ground through Tomà Berlanda’s survey of works by Luca Coffari, Bonetti and Bonetti, Silvia and Reto Gmür, Jachen Könz / Ludovica Molo, Nicola Baserga / Christian Mozzetti / Pedrazzini Guidotti, and Ivano Gianola. Expanding on this theme, the subsequent essay by Ilka and Andreas Ruby illustrated the conception of the ground as an ecology of architecture, identifying multiple interpretations in modern and contemporary design – from Le Corbusier’s «physical and semantic emptying» to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s «conceptual neutralization», and from the «upper layer of a palimpsest» to Rem Koolhaas’s «infrastructural ground».10

Issue 4 of 2014 focused on the reconsideration of the role of the window in certain projects in Italian-speaking Switzerland – Casa Guidotti in Monte Carasso (2009–2011) by Stefano Guidotti and Isabella Polti, a house in Brissago (2010–2013) by Wespi de Meuron Romeo, a single-family house in Ticino (2009–2011) by Colombo+Casiraghi, the wooden house in Cugnasco (2013–2014) by Gionata Epis, and the wooden house in Lugano-Besso (2014) by Bruno Keller11 – where constructive research was prioritized in the design process.

These works were preceded by a significant essay, L’intérieur traditionnel assiégé par la fenêtre en bandeau,12 recounting an emblematic twentieth-century work, Le Corbusier’s Petite Maison in Corseaux (1924), and the related controversy with Auguste Perret over the choice of ribbon windows. Bruno Reichlin first describes the project’s genesis, emphasizing that the idea of a «purist wagon-shaped house»13 aimed to minimize surface waste in favor of the salon and to maximize views through horizontal openings. He then examines in detail the two contrasting positions: Perret’s view that «a window exists to illuminate, to give light to an interior»,14 versus the Swiss-French master, dismayed by Perret’s lack of collegiality, who argued that windows were both his «technical and aesthetic obsession», and that the design of his façades was dictated not by mere «love of extravagance» but by the idea of «letting in as much air and light as possible, in torrents».15

Issue 1 of 2015 presented a portrait of South Alpine holiday homes through Claudio Ferrata’s text on the emergence of the tourist landscape and Luca Ortelli’s reflection on the relationship with the landscape in works such as the Villa Senar in Hertenstein (1933) by Alfred Möri and Karl-Friedrich Krebs, the Casa per un poeta in Ronco sopra Ascona (1939) by Paul Artaria, the Petite Maison in Corseaux (1924) by Le Corbusier, and the Casa Malaparte in Capri (1937) by Libera/Malaparte.16 In her introductory commentary on the works presented, Judit Solt analyzed three recent cases – the Casa Kuoni in San Nazzaro by Conradin Clavuot (2012), the Casa Bula in Mergoscia by Bearth & Deplazes Architects (2013), and the Casa a Monte in Castel San Pietro (2014) by Sergison Bates – identifying a common approach in fostering, through views and interior material choices, a state of «contemplative retreat».17

Principles of relation

To reconnect with the past and bring the discussion back to certain disciplinary references still relevant to contemporary design, the single-family house today seems once again shaped by three enduring principles of relation.

The first is the dialogue with place. In the opening of The Villa: Form and Ideology of Country House (1990), James Ackerman recalled that «the villa cannot be understood apart from the city», because «it exists not to fulfil autonomous functions but to counterbalance the values and advantages of urban life». As an example, he cited an ancient Roman relief depicting a fortified city with a suburban villa outside its walls. This perspective, rooted in the reciprocity between the urban and the domestic, remains valid today for many architects and theorists, expressing itself in new forms of relationship – morphological and typological, direct and indirect, perceptual and symbolic – through which the house engages with its context and landscape.

The second principle concerns experimentation with domestic comfort. In Il progetto domestico. La casa dell’uomo: archetipi e prototipi, Georges Teyssot recalls that the design of the house derives from two intertwined traditions: one, traceable to Vitruvius, locates the origin of architecture in the primitive hut built by humankind at the dawn of civilization; the other, stemming from the modern era, coincides with the moment when the planning of the habitat begins to dominate both design practice and theoretical discourse.19 Teyssot then outlines a valuable itinerary through different domestic spaces – from English and French Baroque courts to country houses with gardens, from the products of the nineteenth-century «domestic revolution» to the concern for hygiene that marked its end, and from the freer, unconventional houses of artists to the disaffection of the «new nomads» toward a single dwelling. This genealogy traces how the idea of comfort has evolved in step with cultural and social change, and points to the necessity of rethinking it in light of the new material and ethical conditions of our time.

The third principle of relation, equally inescapable within this typological field, involves the re-elaboration of the masters’ legacy. In one of the most emblematic texts of this position, Iñaki Ábalos discusses several historical cases – from Mies van der Rohe’s Patio House to Martin Heidegger’s hut at Todtnauberg in the Black Forest, from Jacques Tati’s Machine à habiter in Mon Oncle to Andy Warhol’s Factory in New York – acknowledging the heterogeneity and significance of twentieth-century domestic spaces. His essay sheds light on the origins and meanings of the fantasies we project onto the idea of home while at the same time advocating an updating of this cultural inheritance and a methodological effort to «forget modernity».20

A comparable approach can be found in an earlier monographic issue of Lotus, devoted to the contemporary relevance of certain twentieth-century houses: from Libera/Malaparte’s Casa Malaparte in Capri (1937) to Gerrit Rietveld’s Schroeder House in Utrecht (1924), from Le Corbusier’s Petite Maison in Corseaux (1924) to Gio Ponti’s Villa Planchart in Caracas (1957). Employing the rhetorical figure of hysteron proteron – in which the order of discourse is inverted relative to the natural flow of events – editor Pierluigi Nicolin described the (impossible) influence of later architects, from Álvaro Siza to Santiago Calatrava and from Peter Eisenman to John Hejduk, on those earlier works. Through this deliberate paradox, he suggested how reading certain contemporary buildings can, at times, sharpen our perception of earlier architectures from which they consciously or unconsciously draw.21

Contemporary living

Turning to the current scenario, understanding the consequences of social, economic, and cultural changes on the conception of dwelling fuels various research explorations.

Bill Bryson, in A Short History of Private Life, retraced the evolution of a typical house’s spaces, highlighting profound differences across historical periods not only in spatial organization but also in furnishings, tools, and the materials composing them.22

In Le case che siamo, Luca Molinari described a series of house models – solid, dominant, sacred, transparent, democratic, rootless, invisible – succeeding one another over time, arguing, as we noted at the outset, that the house is the most cherished and stable domain of our lives, yet «the phenomenon least reflected upon in this first quarter of the century».23

With a complementary analytical approach, also moving from models of houses to the individual spaces composing them, Molinari’s subsequent Stanze. Abitare il desiderio – and, in part, the reflections in his essay in this issue of Archi – examined the transformation of domestic spaces over time, reminding us that corridors, stairs, living rooms, kitchens, libraries, bathrooms, changing rooms, bedrooms, balcony-terraces, and cellars-attics24 consist not only of walls, windows, doors, and furniture but also of elements tied to perception – light and color, sound and smell – which, combined, create what Peter Zumthor calls «atmosphere».25

This reflection recalls the radical shift in Europe between the wars, when, as Ignasi de Solà-Morales noted in 1991, housing discourse moved from words such as «progress, rationality, and happiness» to words like «intimacy and subjectivity»,26 emphasizing a closer connection to human dimensions and sensory perception. It was precisely in this historical phase, as evident in experimental houses of the era, that architectural culture began prioritizing individual well-being over community welfare. Alvar Aalto, in his famous critique of the machine à habiter principle, argued that human scale – both physical and spiritual – became the new reference point: «Reconstruction is a necessity without limits in a war that destroys man’s first and oldest protection, the house (…) a house must provide basic protection to the individual, while a community must care for the entire population».27

The past thirty years have also witnessed two further shifts. The first concerns the crisis of a privacy-based housing model in favor of new forms of co-living driven by digital culture,28 exemplified by case studies such as OMA’s Maison à Bordeaux (1998), Bernard Tschumi’s Glass Video Gallery in Groningen (1990), UN Studio’s Möbius House in Het Gooi (1998), and Sean Godsell’s Kew House in Melbourne (1997), presented by Terence Riley in 1999 in the exhibition The Un-private house at MoMA, New York.

The most recent reconsideration of domestic spatiality coincided with the pandemic years, prompting interdisciplinary and multi-scale reflections on urban and building design, interior space and furnishings, material and immaterial dimensions. Two recent publications curated by Michela Bassanelli have invited a renewed focus on certain spaces, such as private outdoor areas (loggias, balconies, terraces), intermediary spaces (atriums, landings, galleries), and shared services,29 while exploring new principles of inclusivity based on difference, coexistence of species, and the desire for community.30

Four houses

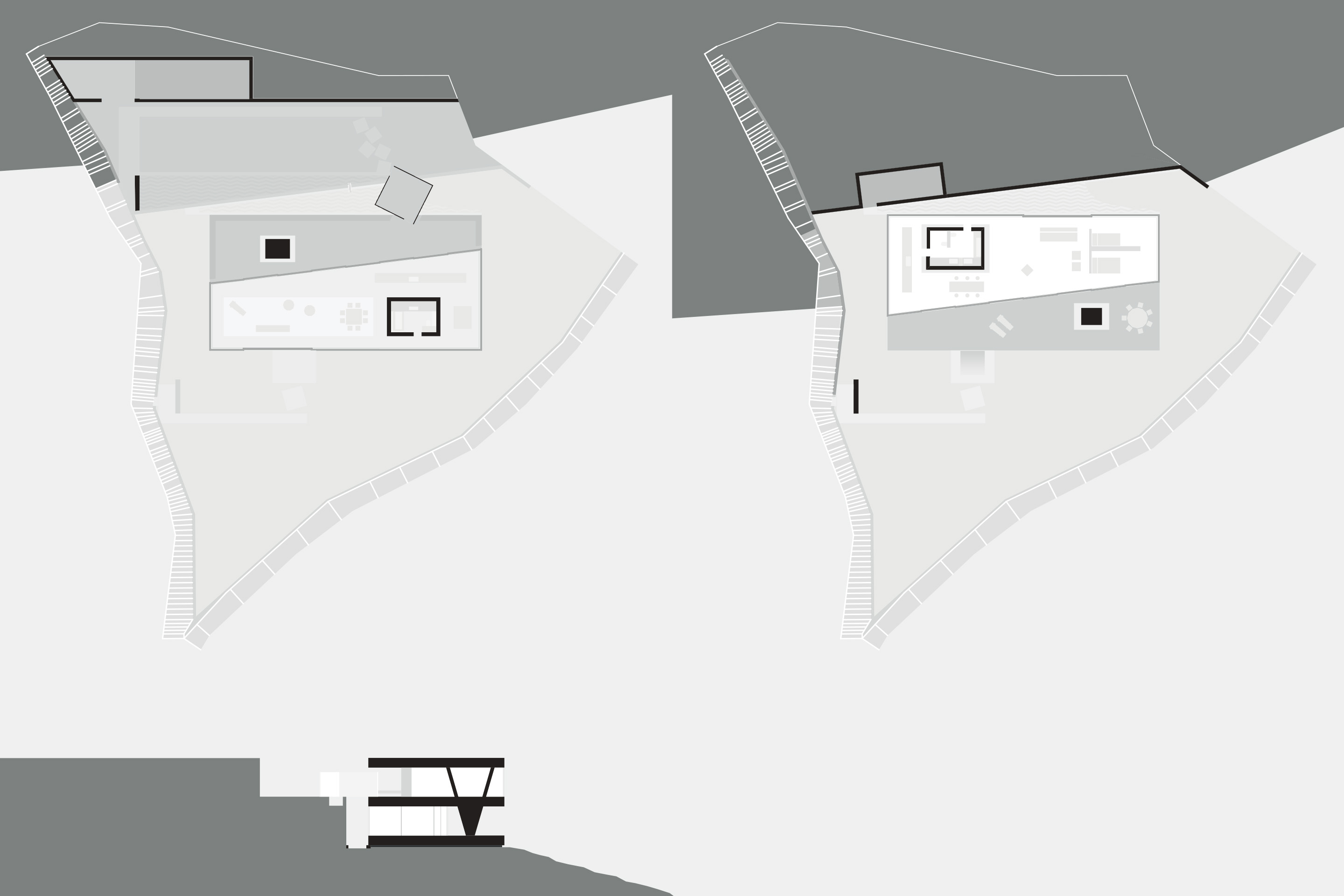

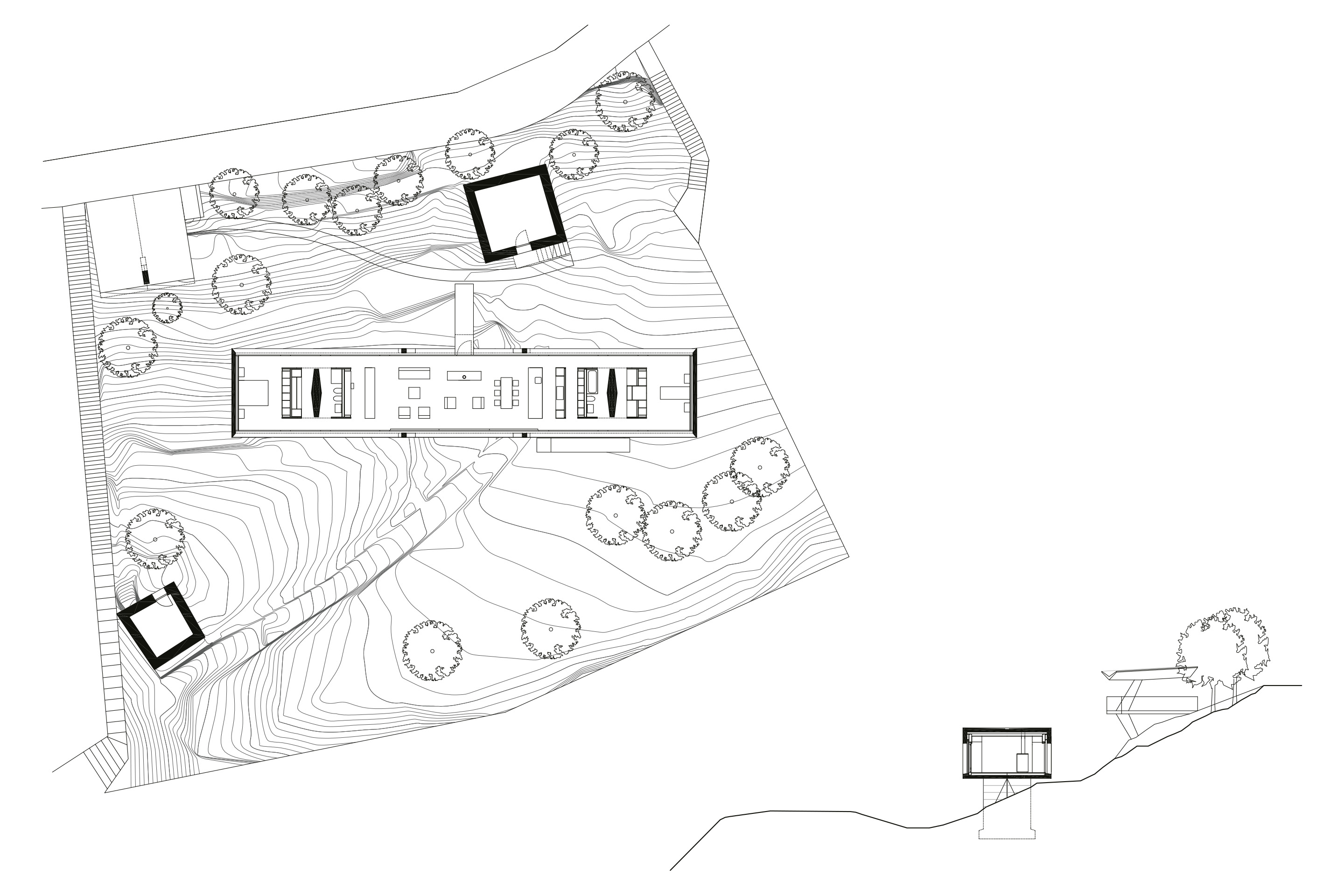

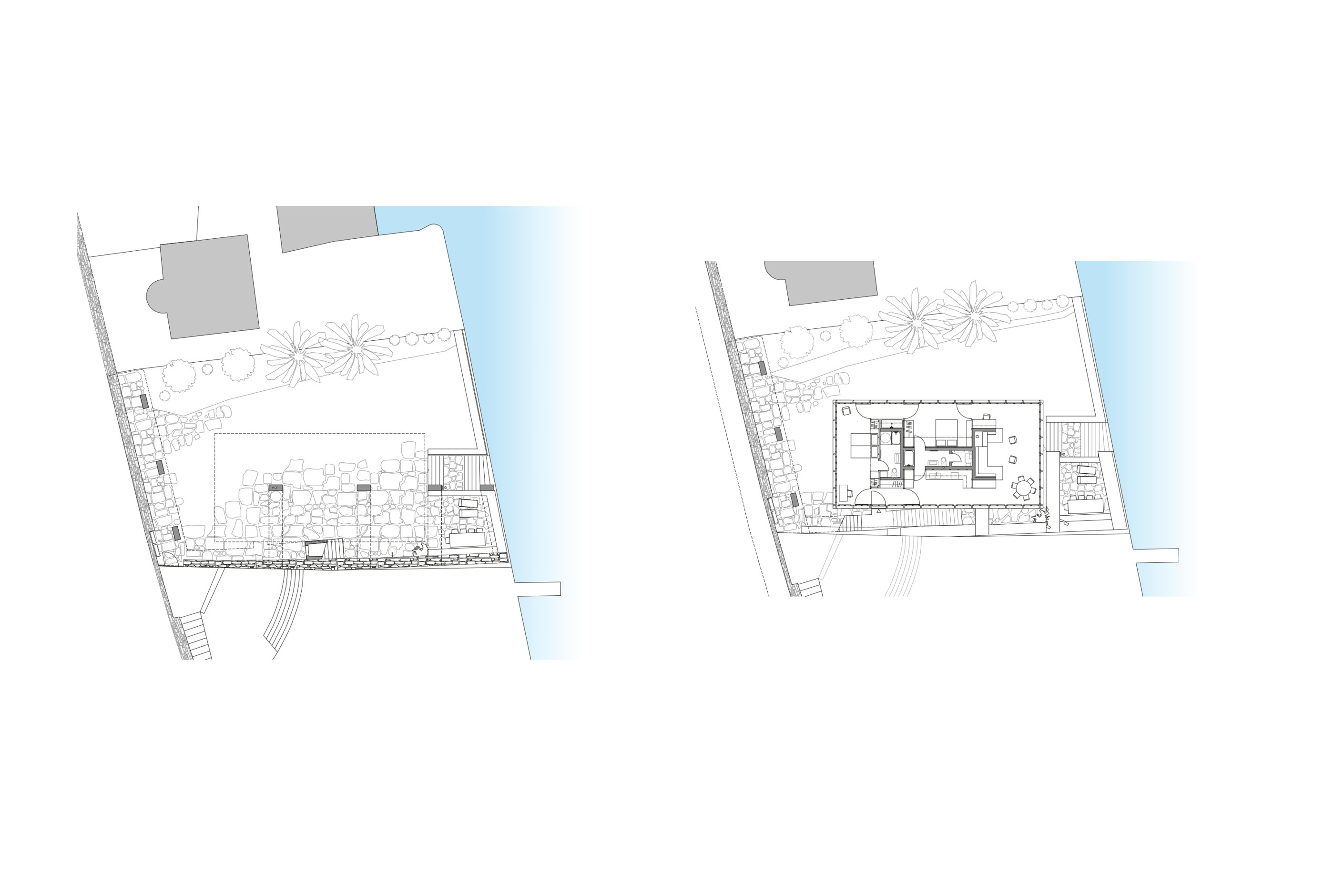

The guiding principle behind the selection of this issue, as in previous editions, is to reflect the heterogeneity of single-family architecture through a spectrum of significant examples: the Casa a San Nazzaro in Gambarogno (2021) by Wespi de Meuron Romeo, the Ca’ del Tero / Casa Cortile in Minusio (2022) by Bartke Pedrazzini, the House in Baden near Vienna (2024) by Balissat Kaçani + Jann Erhard, and the Casa Bula in Schüpfen (2024) by Bearth & Deplazes Architects.

Some distinctions between these works are straightforward: three are new constructions, while one is the transformation of an existing building; two are located in Canton Ticino, one in Canton Bern, and one in Austria (though designed by architects from Canton Aargau); two are based on elementary geometries, two on a clear departure from this principle; two employ modern materials, and two rely on traditional ones such as stone and timber. More nuanced, however, are the different ways these projects interpret three dichotomies within the culture of design that, in the field of the single-family house, we consider decisive in shaping its architectural character.

With regard to the first – the relationship between service and served spaces – in Casa a San Nazzaro, Casa Bula, and Ca’ del Tero / Casa Cortile, the distributive elements maintain geometric coherence with the plan’s internal subdivision, shifting experimentation instead toward the precision of construction details, such as the treatment of handrails, treads, and thresholds. In contrast, in the House in Baden, the twin staircases are conceived as devices of spatial rupture, deliberately disrupting the regularity of the interior and determining the sculptural volumetric structure of the inhabited spaces they traverse.

Concerning the relation between private interiors and exterior spaces, while in Casa Bula and Ca’ del Tero / Casa Cortile the open and green surfaces unfold continuously around the entire building, in Casa a San Nazzaro they are confined to two sides, and in the House in Baden to only one, thus accentuating the hierarchy between the façades and justifying a more distinct variation in the articulation of fronts and the configuration of access routes.31

As for the dialogue between building and context, in Ca’ del Tero / Casa Cortile the pursuit of continuity finds expression primarily through material choices, whereas in Casa a San Nazzaro it manifests on a more symbolic plane, through irregular forms and tactile textures that resonate with the lacustrine and mountainous landscape in which the building is set. Despite their differences, Casa in Baden and Casa Bula interpret this relationship from a morphological and typological standpoint: their volumes echo the outlines of the surrounding urban and natural forms, while the constructive elements recall local constants – most notably the pitched roof, which in both cases is reinterpreted in terms of materiality and geometric structure.

In this regard, the varying conditions of the sites – in some cases open and unbounded, in others enclosed by nearby buildings, and in still others wedged between infrastructures or existing constructions — exert a direct influence on the configuration of volumes and surfaces. The open terrain surrounding Casa Bula enables an extroverted composition, its ground floor wrapped by a continuous glazed ribbon; the road network encircling Casa a San Nazzaro generates a massive, inward-looking form; the peculiar setting of the House in Baden, positioned between tram lines and a sheltered garden, suggests a deliberate differentiation of its façades, with isolated apertures on one side and an entirely glazed surface along the opposite elevation; while the single street-facing side of the Ca’ del Tero / Casa Cortile produces a calibrated variation in the dimension and distribution of its openings.

In representing distinct forms of experimentation – both typological and constructive – the houses in Gambarogno, Minusio, Baden, and Schüpfen lead to a necessary concluding reflection on the broader meaning of this survey.

In Filosofia della casa, Emanuele Coccia argues that although modern philosophy has largely centred its attention on the city, the future of the planet can only be domestic. His invitation is to return to the question of the house, responding to the urgency of «making this planet a true dwelling» while simultaneously «turning our dwelling into a true planet».32

For several years, although single-family houses have appeared in fragments within issues dedicated to other themes, they have not been the focus of a specific issue of Archi. Within this perspective – and in acknowledgment of a paradigm shift already underway, at least on the cultural level – greater attention has been devoted to other forms of residential architecture, particularly collective housing inspired by far-sighted territorial development policies aimed at controlling urban sprawl, optimising resources, and strengthening social interaction.

This does not mean, however, that research on the single-family house has ceased to produce works of significance. As this year – and with it, this cycle of the magazine – draws to a close, it seems appropriate to return to a theme that has shaped many past issues, and to recognise the value of several new projects that have managed to engage meaningfully with the emerging conditions of contemporary life.

Notes

1 Cfr. Luoghi collettivi nella città contemporanea, «Archi», n. 4, 2021.

2 Cfr. L’abitare collettivo, «Archi», n. 5, 2023.

3 Cfr. Forme di qualità urbana, «Archi», n. 5, 2024.

4 M. Daguerre, Artificiale per natura, in Id., Ville in Svizzera, Electa, Milano 2010, p. 5.

5 P. Gallo, S. San Pietro, Ville in Italia e Canton Ticino, L’Archivolto, Milano 2001, p. 7.

6 T. De Venuto, Case in Ticino, Libria, Melfi 2023, p. 9.

7 R. Masiero, Una macchina per pensare. La casa a Paros di Silvia Gmür e Livio Vacchini, Mimesis, Milano-Udine 2009.

8 R. Martinis, Stratigrafie di un’idea, in D. Fornari, G. Jean, R. Martinis, Carlo Scarpa. Casa Zentner a Zurigo: una villa italiana in Svizzera, Electa, Milano 2020, p. 57.

9 N. Navone, Satisfaction de l’esprit. Progettare, costruire e narrare una casa, in N. Navone, A. Ruchat, Una casa sul lago, Officina libraria, Roma 2023, pp. 34-36.

10 I. Ruby, A. Ruby, Groundscapes. L’incontro con il suolo nell’architettura contemporanea, «Archi», n. 1, 2013, pp. 17-22. Il testo è anche l’introduzione al volume | The text also serves as the introduction to the volume I. Ruby, A. Ruby, Groundscapes. The rediscovery of the ground in contemporary architecture, Gustavo Gili, Barcelona 2007.

11 A queste opere si aggiungono due residenze collettive | These works are complemented by two collective housing projects Cristiana Guerra, Casa d’appartamenti a Bellinzona (2013-2014), Michele Arnaboldi, Raffaele Cammarata, Residenze al Gaggio a Orselina (2008-2012).

12 B. Reichlin, L’intérieur tradizionale insidiato dalla finestra a nastro, «Archi», n. 4, 2014, pp. 43-49. The text is an excerpt from the essays included in Dalla «soluzione elegante» all’«edificio aperto». Scritti intorno ad alcune opere di Le Corbusier, Mendrisio Academy Press, Mendrisio 2013, che raccoglie alcuni scritti dedicati dagli anni Sessanta in avanti da Bruno Reichlin a Le Corbusier| which brings together a selection of writings that Bruno Reichlin has dedicated to Le Corbusier since the 1960s.

13 G-É. Jeanneret, Diario in data 27 dicembre 2023: «Ed fait des plans très simples, d’une maison puriste, forme wagon, un seul rez de chaussé».

14 G. Baderre, M. Auguste Perret nous parle de l’architecture, «Paris-Journal», n. 2478, 07.12.1923, p. 5.

15 G. Baderre, Une visite à Le Corbusier-Saugnier, «Paris-Journal», n. 2479, 28.12.1923, p. 3.

16 L. Ortelli, Balconi, terrazze, paesaggi e storie di gente che ha cambiato nome, «Archi», n. 1, 2015, pp. 31-36.

17 J. Solt, Il prezzo della bellezza, in Archi», n. 1, 2015, p. 41.

18 J. Ackerman, La villa: forma e ideologia, Einaudi, Torino 1992, p. 3.

19 G. Teyssot, Figure d’interni, in Id., Il progetto domestico. La casa dell’uomo: archetipi e prototipi, Electa, Milano 1986, p. 18.

20 I. Ábalos, Il buon abitare. Pensare le case della modernità (2000), Marinotti, Milano 2009, p. 220.

21 P. Nicolin, Abitare nell’architettura, «Lotus», n. 60, 1988, p. 5.

22 B. Bryson, Breve storia della vita privata, Guanda, Parma 2010.

23 L. Molinari, Le case che siamo, Nottetempo, Milano 2020, p. 11.

24 L. Molinari, Stanze. Abitare il desiderio, Nottetempo, Milano 2024, pp. 20-21.

25 P. Zumthor, Atmosfere, Electa, Milano 2008.

26 I. de Solà-Morales, Architettura e esistenzialismo: una crisi dell’architettura moderna, «Casabella», n. 583, 1991, pp. 39-40.

27 A. Aalto, La fine de la machine à habiter, «Metron», n. 7, 1946, pp. 2, 4.

28 T. Riley, The Un-Private House, The Museum of Modern Art, New York 1999.

29 M. Bassanelli (a cura di), Covid-Home, LetteraVentidue, Siracusa 2020.

30 M. Bassanelli (a cura di), Abitare oltre la casa. Metamorfosi del domestico, DeriveApprodi, Bologna 2022.

31 On this specific aspect, see also the innovative interpretation of covered outdoor spaces presented in the following pages, in Laura Cristea and Raphael Zuber’s House at the Black Sea.

32 E. Coccia, Filosofia della casa. La spazio domestico e la felicità, Einaudi, Torino 2021, p. 11.