The structure by parts

Interview with Gustav Düsing & Max Hacke

The second interview addresses Gustav Düsing and Max Hacke, recipients of the prestigious EU Mies Awards 2024, in a reflection linking sustainability and digital design issues, starting with their most recent projects.

Per la versione italiana cliccare qui.

Carlo Nozza: Archi magazine is aimed at both architects and engineers, and I would like to start by talking about your working process and your approach to some of the issues at the centre of the debate in the field of construction. What working method did you adopt to design this building, the Study Pavilion TU-Braunschweig, where we are located and for which you were awarded the prestigious EU Mies Awards 2024? It is quite clear that it is an attempt to disseminate an innovative and flexible way of making architecture, which guarantees the possibility of easily adapting the space over time, up to the complete disassembly of the structure for its complete reuse.

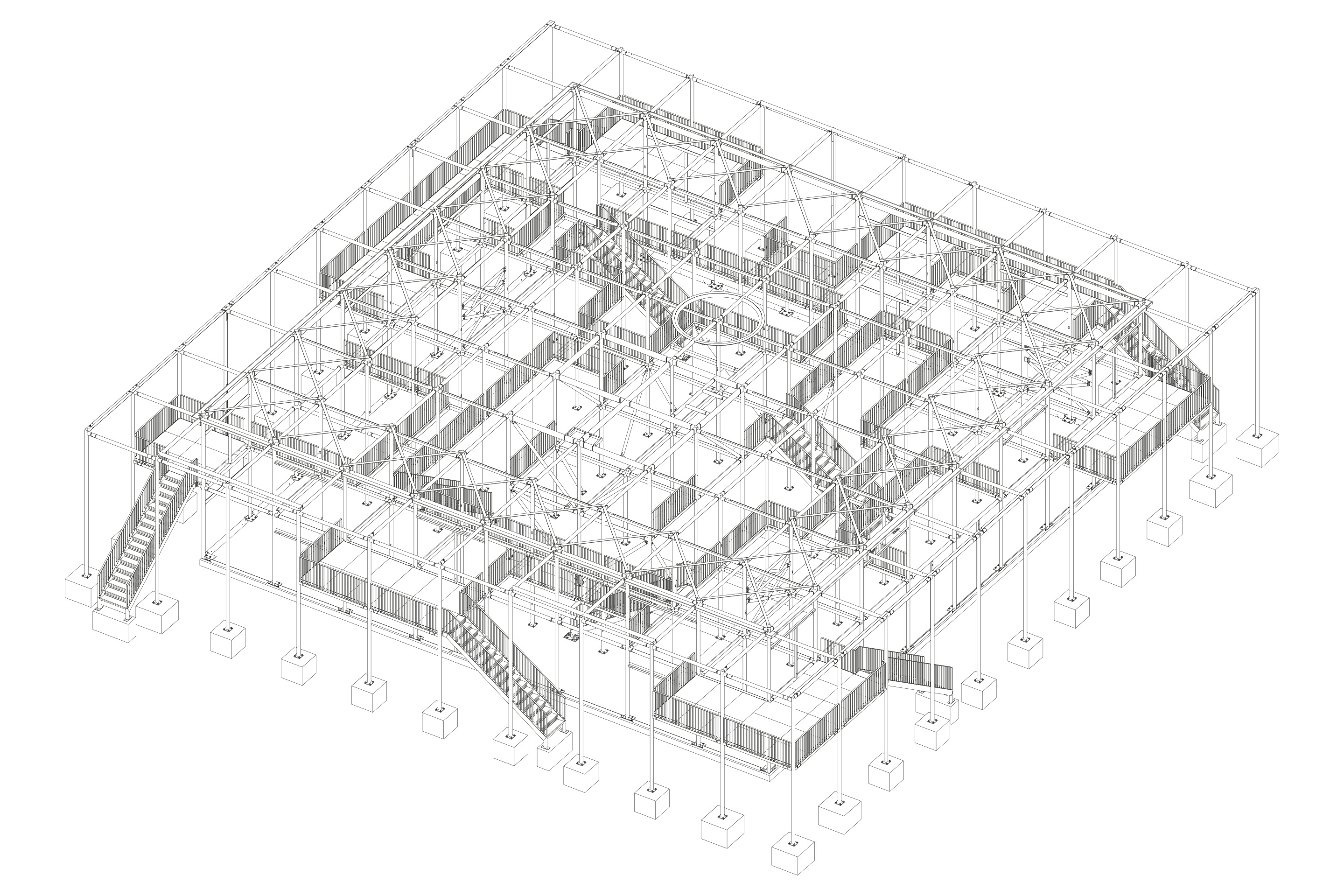

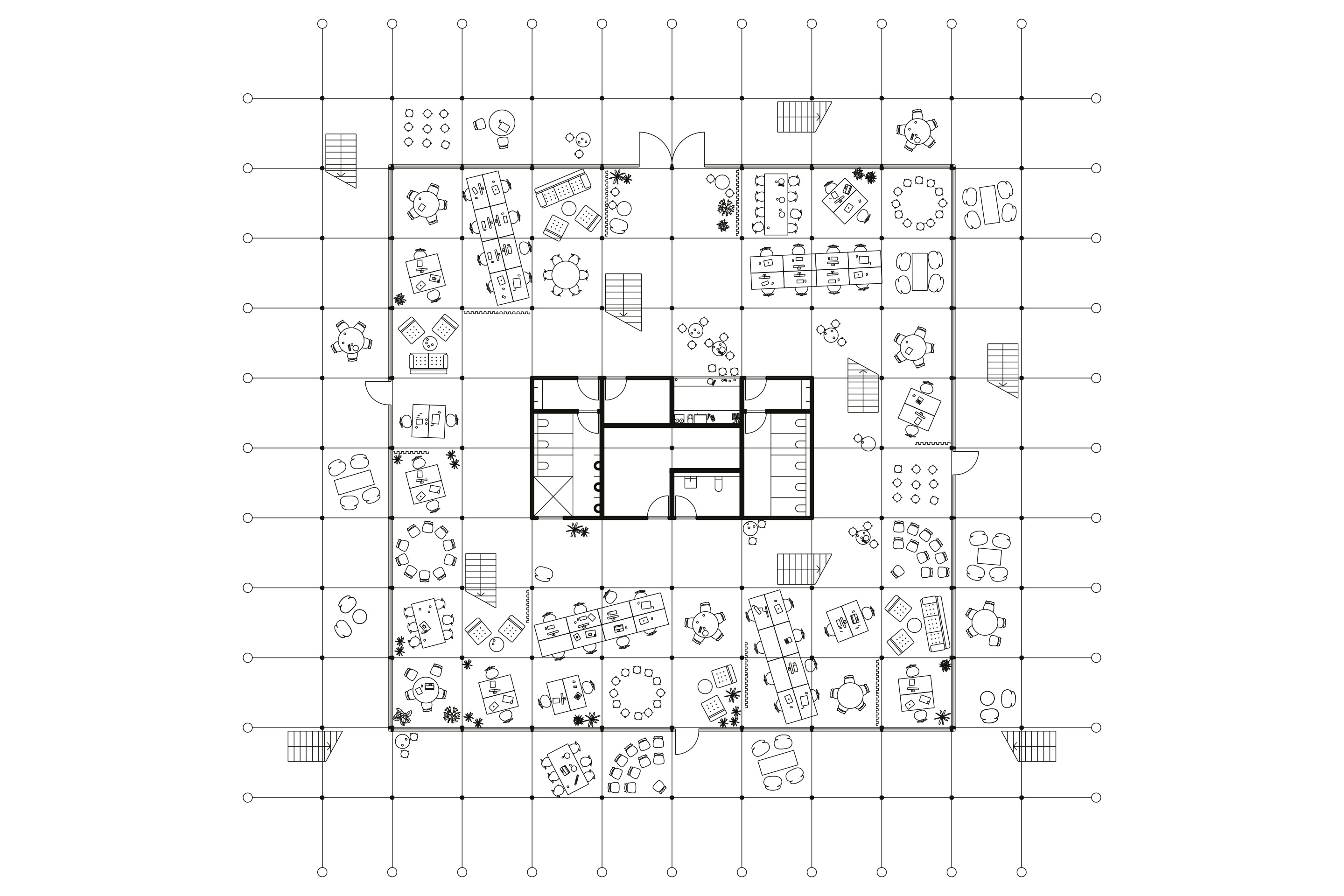

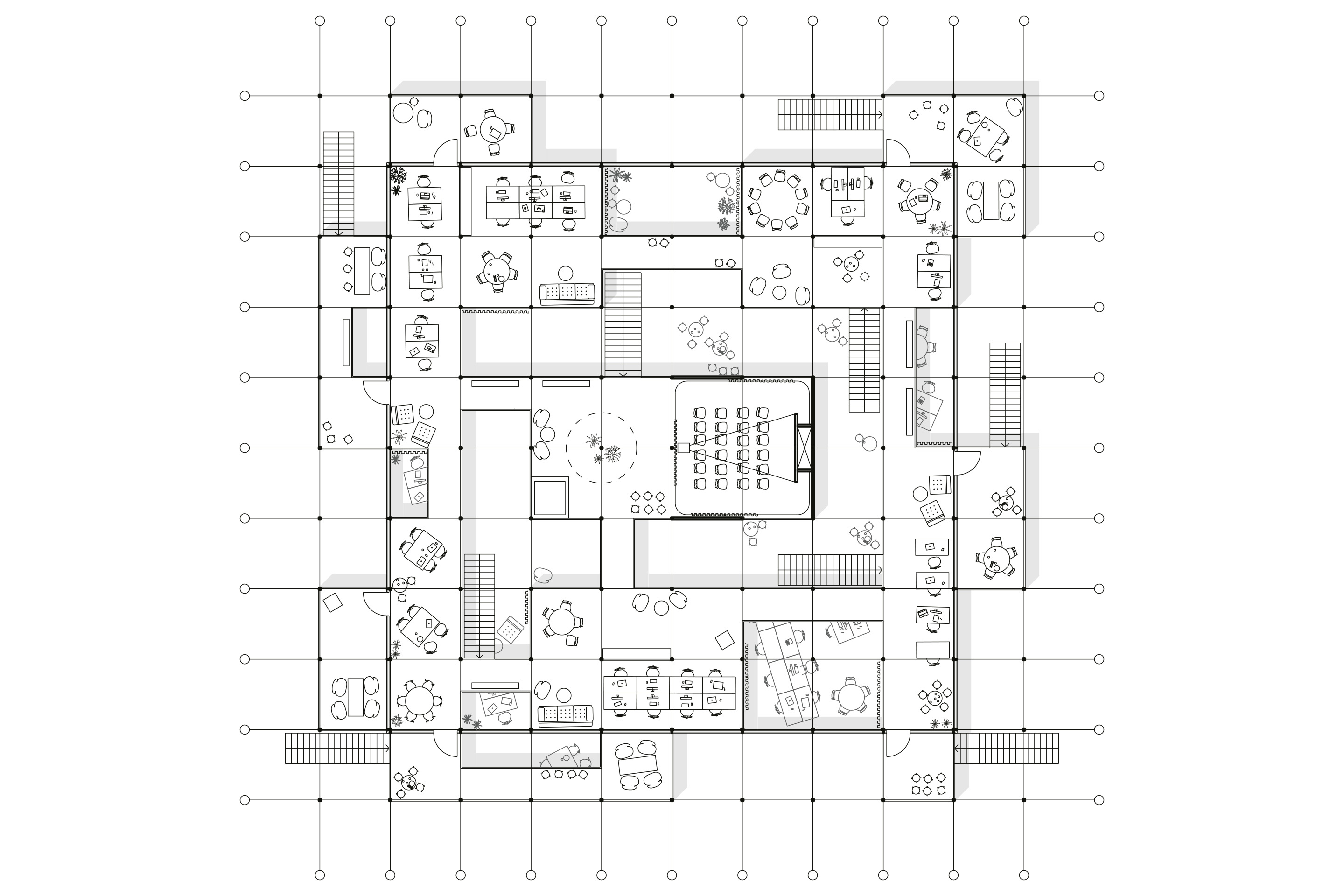

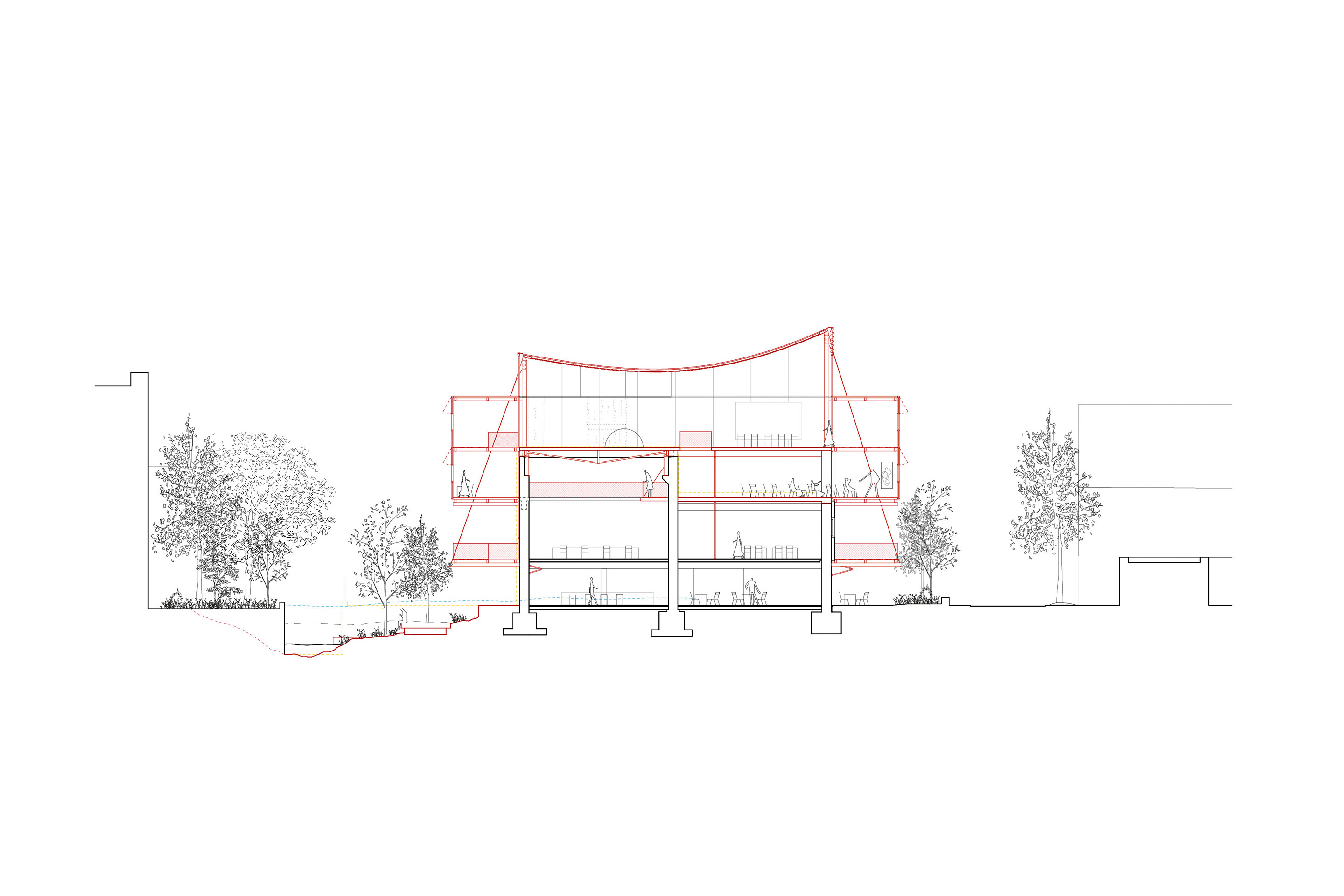

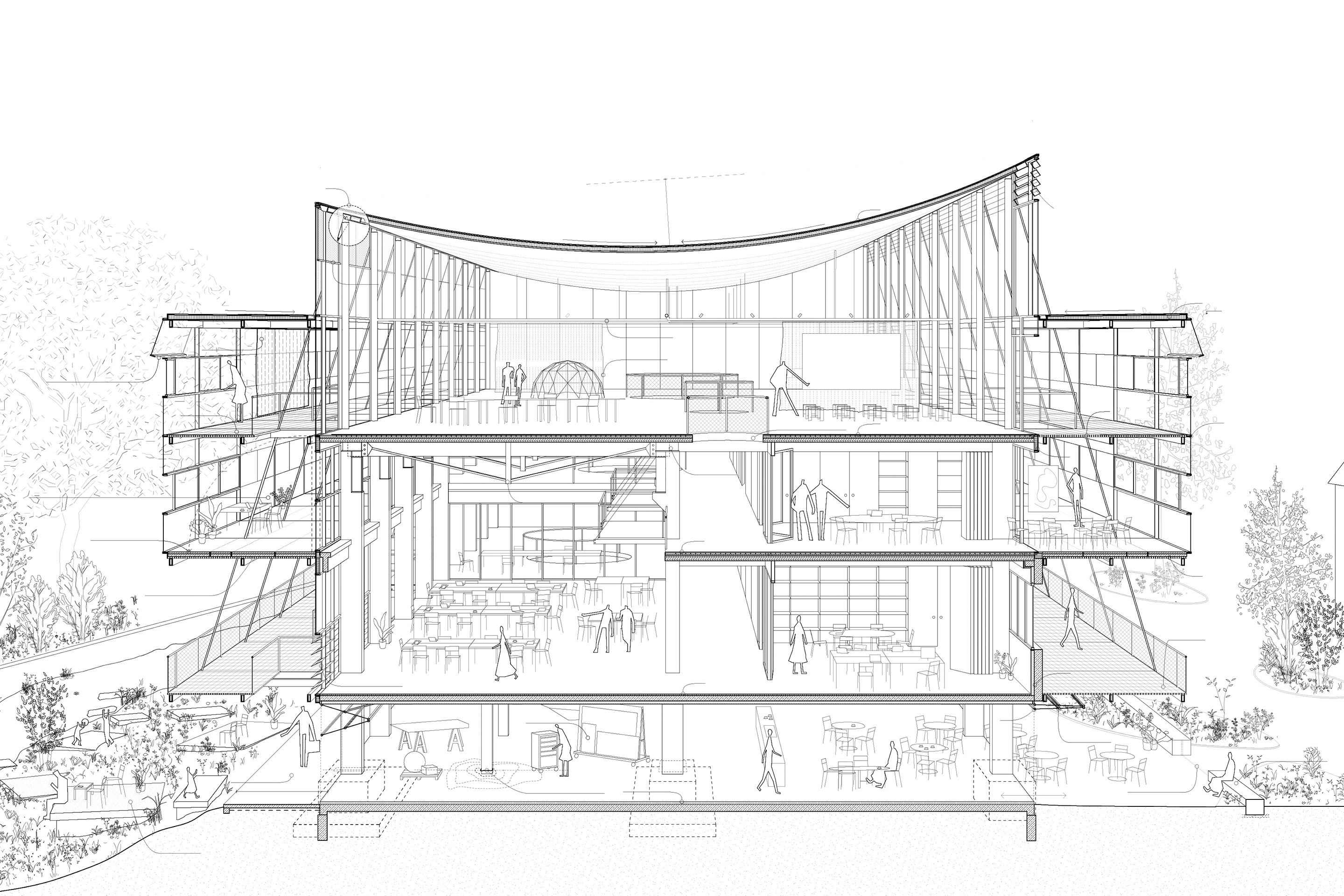

Gustav Düsing & Max Hacke: Indeed, the way the building was designed and how it looked once constructed was the result of designing for a specific programme, in this case a building for individual study and group training at the Technische Universität Braunschweig. We know that this type of programme is extremely variable and will certainly continue to change in the near future in ways that are difficult to predict, so the container had to be able to easily be adapted to the changing needs of use over time. For these reasons, as a starting point, we told ourselves that the entire load-bearing structure and every element within it had to be designed to be easily modified at a much faster rate than is typical today for large container buildings in the advanced tertiary or educational sectors. We wanted it to be possible to make any adjustment or change very easily and very quickly, for example by using lightweight materials and dry construction systems, set up with simple mobile platforms, bolts and screwdrivers. This is the idea we started with. Based on the same principles, it was immediately logical for us to use prefabricated, modular, dry-assembled steel elements for the structure, because they were strong, light and easy to manoeuvre, and then, in collaboration with the engineers, to design nodes and joints that were always accessible, easy to implement and reversible. With these parameters and the idea of a transparent, continuous and easily accessible space, we decided that the structure should be light and therefore small.

History teaches us that it is possible to realise column-free spaces with large external exoskeletons, such as Mies van der Rohe’s Crown Hall at the IIT campus in Chicago, but we decided to take a different approach, proposing to realise flexible spaces with a small structure, laid out on a three-dimensional grid, where it would be easy to insert and remove individual elements or change entire parts of the functional programme. In other words, the exact opposite of Crown Hall, which was made of lightweight structural elements, easy to assemble and certainly less expensive. Around 700 lightweight metal profiles were used in this building, all of which were identical and easy to produce economically.

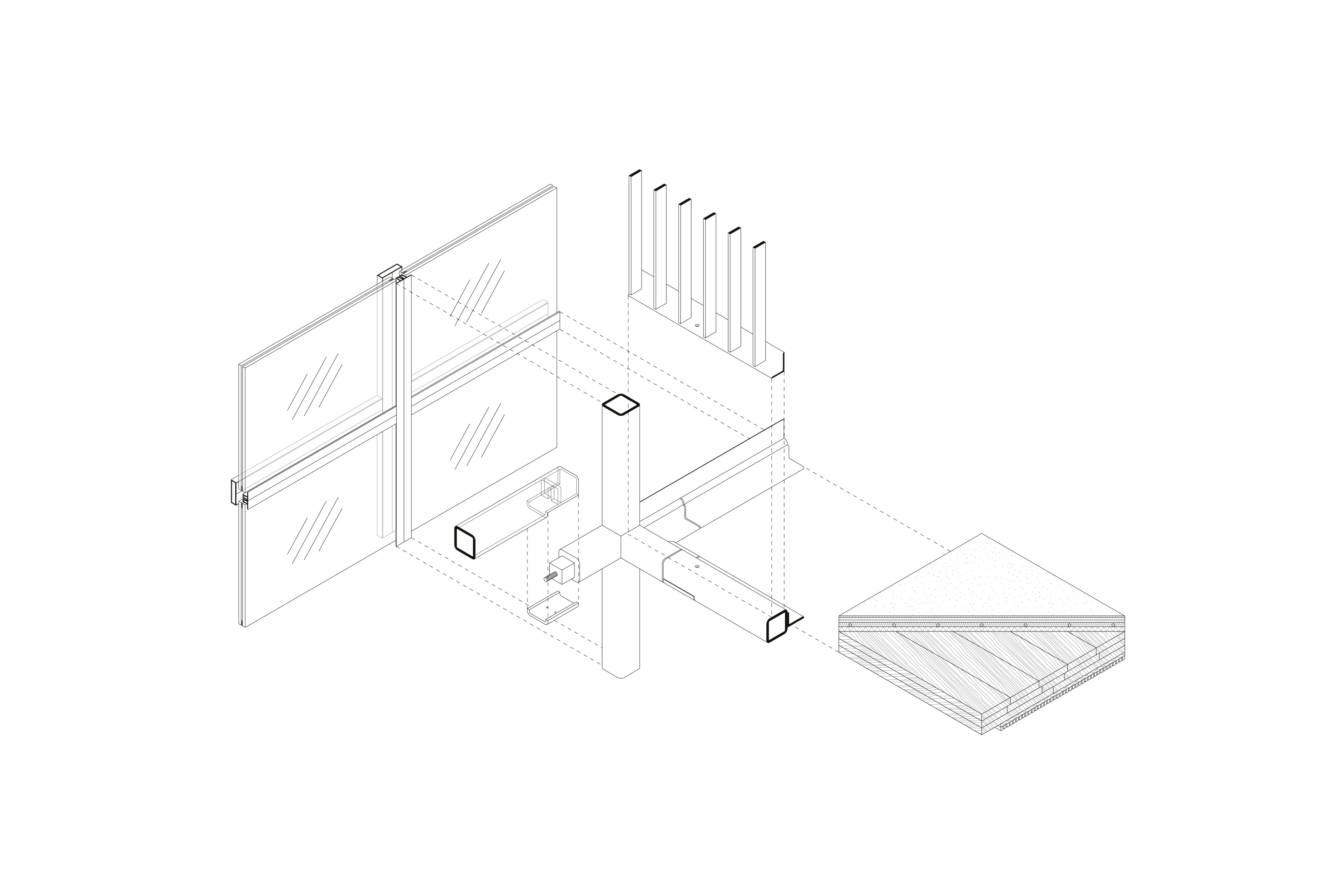

So it was with this idea, perhaps a little naïve at first, that we, as young architects with little experience, started the project from a single element, a 10x10 cm hollow steel profile, which would then be combined with the other elements, such as structural joints, ceiling slabs, floors, stairs, roof, façade, curtains, handrails, all the finishing materials, etc. In this way, with a relatively limited set of parts, just nine different elements, repeated over and over again, you get a huge number of spatial configurations that create a comfortable and beautiful space to be seen, lived and experienced in hundreds of different ways. So with a relatively limited set of parts, just nine different elements that are repeated over and over again, you get an almost infinite number of spatial configurations that create a comfortable and beautiful space that can be seen, lived in and experienced in hundreds of different ways.

Another thing that interested us about this type of steel element is that it is a hollow profile that, in addition to being part of the structure, could also contain the building’s technical infrastructure, such as electrical cables, so that we could also integrate lights or sockets to connect students’ laptops, for example, directly into the structure. This really allows a flexible use of space, as this technological infrastructure can also be easily adapted countless times.

The same principles were adopted in the design of all the other components of the building, such as partitions and dividing walls, and in the end it was a pleasant surprise to see the general appreciation of this project by the students who live in it and, more generally, by the architects and professors, some of them very well known, who work in this university. It is a public building, light, transparent, using renewable energy and promoting a democratic use of space.

CN: The building looks neat and well controlled in its realisation: how important is the design of the construction of the architecture in your work process? Did you directly supervise the design of the executive details and the construction management?

GD & MH: Our design ambition was to reduce the visibility of the joints, as we wanted the whole structure to look like a thin frame for the space, without the joints obstructing the view.

For this reason, we preferred to use a square profile, which is as thin as possible, in order to optimize the structure. The square profile is neutral, without direction, unlike the L-beam which has many visible sharp edges. The L-beam always has two different faces and therefore two different possible connections. In contrast, the square profile behaves in the same way in all directions and, when assembled, all the elements are continuous and aligned in the same plane.

We followed the entire design and manufacturing process, although the structural calculations were, of course, carried out by Knippers-Helbig. The engineers had advanced calculation software and we played a sort of ping-pong with them. Based on our initial idea, they first proposed a scheme for the model joint, which we then developed together through numerous variants, always trying to simplify it to make it as neutral as possible. One part of the joint is welded and another is screwed. The welded part fits and closes the edge of the rounded square profile, which we cannot avoid because the roundness of the edges is determined by the way it is made and its radius depends on the thickness of the profile wall. It is a matter of production. So if you want a connection element in direct contact with the profile, it must always be shaped at the corners. This situation is solved by using plates that are welded along the edge of the square profiles, while all other connections between the elements are always bolted. The typical situation is therefore a cross between welded elements that are then bolted and finally covered and hidden by a shaped plate that makes the assembly as neutral as possible, leaving only the slots for assembly and structural tolerance visible. The only exception is the attachment to the curtain wall structure, which is completely autonomous and self-supporting. Here, a split linear element has been added to maintain the same type detail and add the thermal break.

So when you look inside through the window, you can still see the classic type of cross joint. The upper beam is the primary one, because it carries the corrugated sheet and the load, while the one in the other direction is the secondary one, because it carries itself and acts as a stiffener.

The collaboration with the engineer was decisive because it was the first work for us and the system, although very simple, was customised and optimised. In general, no company is willing to produce this type of non-standard solution; designers have to become almost friends or at least find a common language and harmony to patiently define the feasibility of the solution, hoping that a company will eventually make an offer.

CN: The choice of material is directly related to the atmosphere it can create, the architectural result. In what direction is your research heading in this field?

GD: It all started with an aesthetic idea, a vision, and Max and I often have different ideas about architecture. In the case of this building, I think the idea of using steel worked very well to achieve the final look we wanted for the building: light, transparent, flexible and supported by a very thin and homogeneous three-dimensional modular mesh. I like the idea that it looks partly like magic: how does it hold up? Why is it so thin? Why is it so fragile? When that happens, people will see its beauty. So I like steel, and it has great potential for the future because now, at least in Germany, the steel on sale is plentiful and 100% recycled. Then steel is also a circular resource because it can be recycled over and over again, today with energy from renewable sources, in the future there will be hydrogen furnaces. I also think that lightweight steel structures work very well, especially in public buildings, to represent the idea of transparency and therefore inclusiveness.

Of course, steel is only used where it makes sense, for example in structures, in other cases other materials are used. In this building, the floor support is made of wood from certified sources because it is light and very thin when used in the horizontal floors. If we replaced it with precast concrete, it would be much heavier, we would have higher loads and the profiles of the structure would be much larger.

It is essentially a steel and glass building. At a time when the general consensus was to build with wood, earth and compostable materials, we chose steel, and I think this is one of the fascinating aspects of this building that led to it winning numerous awards.

CN: One can clearly perceive that great attention was also given to the acoustic control of the rooms.

GD: There has been a lot of research, one of the main successes of this building is that people feel comfortable talking even in a continuous space where partitions are kept to a minimum and are often made of textile material. Everyone can understand each other, even if there is someone next to them talking loudly.

CN: In the face of climate change, the international debate over the past decade has been marked by numerous declarations of principles and initiatives aimed at promoting and implementing sustainability at various levels (from the UN’s 2030 Agenda to the Baukultur Strategy of the Swiss Confederation). Specifically, in the fields of design and construction, what is your position on these topics?

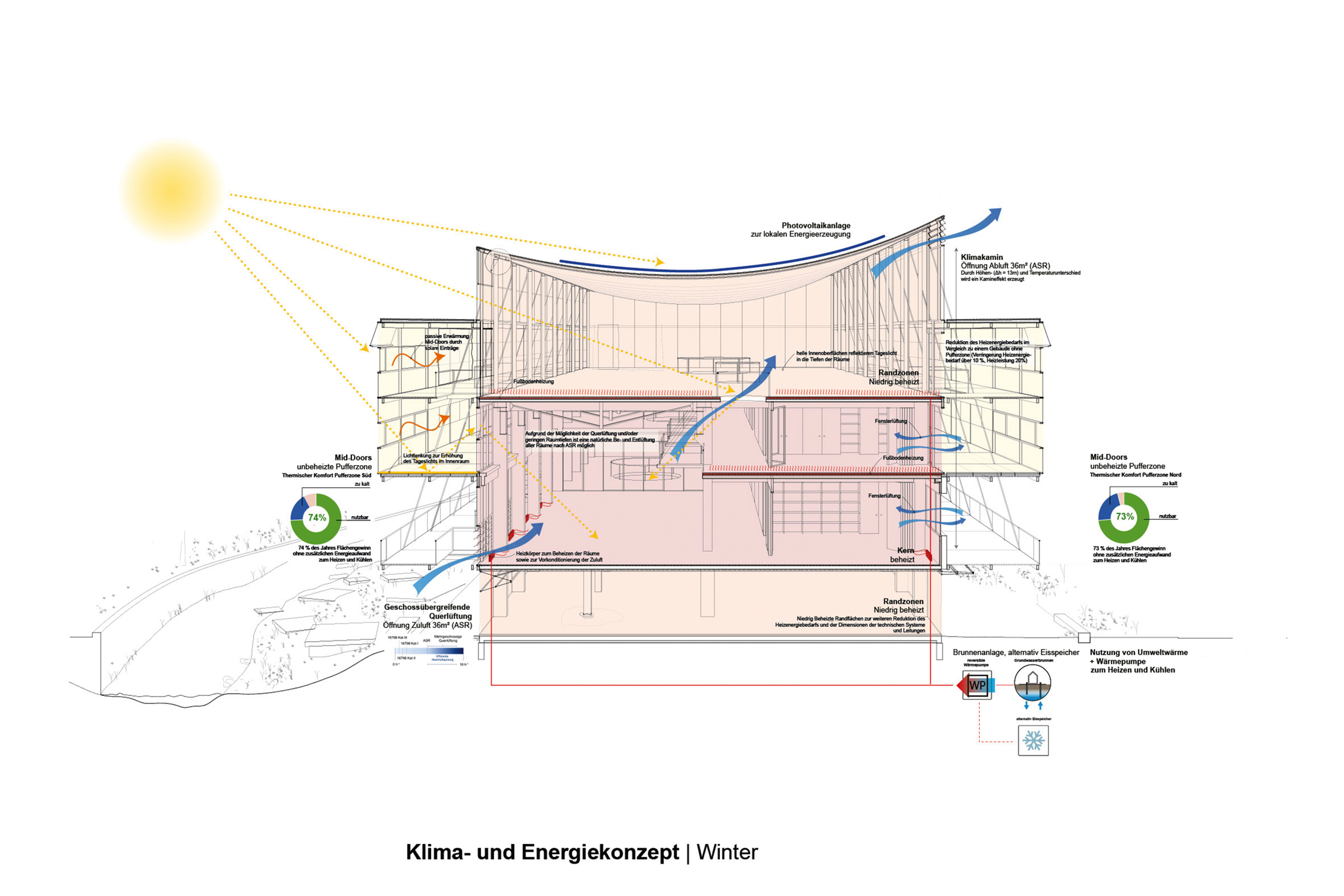

GD & MH: We believe that there is a connection between the performance of the building, its use, its construction principles and the choice of materials used for construction. However, the answer is unique and specific to each project, and we find this fascinating because it brings us back to a freer vision of architecture. It is necessary to study in depth the function of a building, its use and why we build it, in order to arrive at a logical construction principle, a coherent and sustainable system of installations through the selection of responsible materials. In this case, we chose materials suitable for a building for public use, while the underfloor heating and cooling system is connected to the city’s district heating system. At first people were afraid that it would be too hot in the summer because of the large windows, but in fact it is comfortable because the façade is completely shaded. You are lucky, you have chosen the right day to visit, today the weather is fine and the natural light inside gets better and better as the sun rises. In winter, the trees around here lose all their leaves, the sun is low and penetrates deep into the south façade, creating a pleasant warmth inside the building. In the summer, the sun is higher, the trees are covered with leaves, and together with the overhangs of the roof and the loggia, they protect the façade. It all works quite well. The presence of this particular type of tree was important to us from the beginning, even though German law does not allow it to be included in energy balances. The glass is the standard double type, but it works well. Even in winter, people sit close to it because it is never cold, and the ventilation prevents moisture from building up on the façade.

CN: In terms of your research into the social and technological spin-offs of your projects, where are you heading?

MH: It is interesting for me to consider architecture as a social infrastructure. I defend the idea that architecture should be a common platform, whatever its use, and that when it is highly flexible, it creates a sense of community, whether it is housing or, as in this case, university facilities. This is an idea that I project, or try to project, into every proposal regardless of the programme, and I think it leads to an exploration of how people use or appropriate a building, how this can generate greater freedom in everyday life.

I work on solid wood buildings as well as steel or masonry buildings, but I believe that the choice of materials and the provision of as much flexibility as possible in the comfortable and informal use of spaces are always issues that need to be introduced and carefully considered.

GD: I agree, and I also like the idea that engineering, especially structural engineering, is an important part of architecture. I find a great taste for buildings made of elements, and I like them to be light and transparent.

CN: «How much does your building weight?» R. Buckminster Fuller asked N. Foster one day...

GD: Exactly in this direction I am trying to combine the ideas of modularity, tensile structures and membrane structures. I often do installations where I try to test these kinds of solutions because I am convinced that research into structural innovation is interesting.

CN: So you are interested in the research and works of Frei Otto?

GD: Yes, of course, he is a reference and I think there is a lot of his research that we can follow. For example, I am interested in the structures of the Olympic stadium in Munich, but I would like to find a way to avoid the use of reinforced concrete and thus reduce plinths and other large ground works. Otto was also a pioneer of sustainability, organising seminars on climate, passive architecture, biomaterials, etc., way ahead of his time.

CN: Do you know the Swiss architect Fritz Haller?

GD: Yes, of course it is another reference. We see great potential in projecting his ideas into the future. I think we can combine his modular building systems with the more contemporary issues of sustainability. Otto, Haller and Fuller are good references for innovative research into sustainable construction.

CN: What tools do you use to work?

MH: I think freehand drawing is still a very free and powerful tool. I like to put ideas on paper, but I don’t want to lose the possibility of dialogue, where collaboration plays a decisive role. I think it is the best tool to conceptualise different subjects.

GD: 3D digital design is also free, and therefore all tools can contribute in their own way to making the design process flexible and liberating.

CN: During the design process, did you ever think about the maintenance of the building over time and what will happen at the end of its life?

GD: Yes, of course, for example this building will have to be disassembled because they want to build a skyscraper here or something like that. So let’s imagine that they move it to another place, dismantle it and put it back together again. Or with the disassembled parts they will build different buildings and put them together in a different way.

Recently an intern in the studio didn’t have much to do, so I told him: «Start thinking about what to do, you have the 3D model, all the nodes and or joints, try to design new buildings using the same elements as the Study Pavilion at TU-Braunschweig».

I would like, maybe at the end of our career, to see this building move somewhere else and be born into something else. We like of it as think that this is a recyclable building, not only in terms of materials, but especially as a construction system. Reuse can certainly also be a strategy for sustainability. Today most interventions, at least here in Germany, concern existing buildings and these can make an important contribution to reducing the impact of construction on the environment.

CN: So do you support the idea that, right from the design phase, a building can be conceived with the prospect of itself becoming a source of construction material for the future? How do you think the debate around the processes of circular design and construction will evolve? How do you imagine the future transformation of this building?

GD & MH: This project is very efficient, but also very specific. Whatever you want to build by reusing its components can only be based on a 3x3 m grid. That is the nature of it, and you can do a lot of things like build a very long building but only 3m wide and so on. It is a system for constructing buildings of a medium scale, between that of traditional buildings and that of furniture.

When we talk about this building in lectures, we always show the projects Spacial City by Jona Friedman and FunPalace by Cedric Price, and we say that the design comes from there, that somehow we started from the experimental architecture of the 1970s.

MH: We think that this building somehow provokes the idea of how culture is also produced through thinking and designing how people can inhabit the space and how they can perhaps take care of it. The hope is that it becomes more and more the heart of the campus that people will identify with it and that it become a cultural trigger. We architects often know and believe in the potential of architecture, but we have to deal with many people who do not see it or do not want to see it.

GD: I think one hope for a better future is to promote socio-cultural innovation through architecture. My role as an architect is to show that this is possible. I would like to see the return of bolder ideas in the debate, to move our discipline away from simply solving everyday problems and towards new insights for a better future. I think architecture at the moment, at least here in Germany, relies too much on engineering. I believe the architect as a designer should deal more and better with the «frame space» or the container of the facts of life. I think that this has the potential to become a real movement and that it can achieve the strength that modern had.

CN: Based on the experience and success of this project here at the TU-Braunschweig, are you investigating how to use other materials in your more recent work or are you developing different construction systems?

GD: In recent projects I am often confronted with the adaptation of existing structures. There is a project in which we adapted the prefabricated concrete structure of an old typography. It is therefore a modular structure, which in a sense can also be dismantled, made up of very common elements, and the plan is to add volume and thus increase the height of the building. With the engineers, we looked at the structure and said that the solution could be to add a kind of exoskeleton to reinforce and then raise the existing building. Then, with a very lightweight modular system, we added a habitable structure, trying to distribute the new loads in a balanced way to avoid having to build new foundations. It is still a demountable structure, but in this case it adapts to the existing conditions. That, I think, is the challenge.

CN: To conclude, what is your wish for the near future?

GD & MH: Architects often lazily think that it is impossible to do good architecture, partly because of the huge amount of legislation we have to comply with. Actually it is not, but few really try, people need to have brave ideas and more confidence to do what they want.

It’s about going back to tradition and considering, for example, passive solutions in buildings. There are many very efficient ones that work well in most parts of our planet and the technology should be simplified anyway. Spatially and socially, we should give continuity to the achievements of the modernity in order to concretely move towards a better world.