The expressive impact of detail in structure

Interview with Neven Kostic

In this interview, Neven Kostic shares his innovative approach to design, focusing on interdisciplinarity, the use of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence and digital fabrication, and sustainability.

Per la versione italiana cliccare qui.

Carlo Nozza: During the lecture L’incertitude et la médiane» at the EPFL some time ago, you said that opening up engineering research to other sciences is very important to you. How do you see interdisciplinary collaboration, which is often a source of inspiration and ideas for innovation?

Neven Kostic: I believe that in order to fully understand and respond to challenging projects, the structural engineer needs to consider insights from a variety of engineering disciplines, not just traditional structural engineering. One of the pillars of engineering is the ability to bring together ideas from different fields. In my presentation at EPFL, I gave several examples, such as the first use of lattice girders in shipbuilding, or the use of plates outside the structural context. Interdisciplinarity in structural engineering is everywhere. I am very interested in optimal structures, and the best interdisciplinary example here is nature itself. I know is not a new comparison, but is somehow always beautiful in itself. Everything we create as humans is the result of artificial, unnatural interventions. To achieve «natural beauty» in projects, you have to behave as nature does and never add anything more than is necessary. A hunting animal cannot be obese, it must be fast to survive. Man, on the other hand, does not always follow nature and tends to add the superfluous, not only because it makes an element stronger and safer, but also because it makes it richer or more valuable. Nature defines things as they should be, optimises them and makes them beautiful. Here is one of the many reasons for the interest of civil engineering in other sciences and interdisciplinary collaborations. These are the references for innovation.

CN: What you have said so far makes me think of Frei Otto, who headed the Institute for Lightweight Structures in Stuttgart between 1964 and 1991, where he developed various research projects on nature’s own structures. What do you focus on when you start developing your structural systems?

NK: I am referring to a specific problem. I must admit that I may not be a great researcher, but I am more interested in solving precise and concrete questions; therefore I do not do investigations if there is no question to solve. When I develop structures, in an already defined context, I try to address and solve problems, avoiding creating new ones, all in respect of architectural work.

CN: What is your opinion about the ongoing technological evolution, e.g. regarding the use of digital tools and fabrication, as well as AI?

NK: I am very interested in these topics and I really believe in the progress they will bring. When I hear people talk about digital manufacturing, I always imagine something completely different from what is being done today, a future where robots will be working alongside humans on construction sites, helping them with the heaviest or most dangerous tasks. So I expect that very soon we will see automated design and assembly on construction sites, as we already see in automotive factories.

As for artificial intelligence, I am already using it in my work. I think AI is a useful tool, not a threat, because it is probably best at what I have the most difficulty with. We have to be open to using these new tools, many new things will come to our professions soon, but I don’t think architecture or engineering will disappear. Finally, I was very surprised when I spoke to ChatGPT, and out of interest I asked it to do a structural check, which it did correctly. AI structural checks, which will come one day, will be the result of a machine, but to find a solution you’ll still have to imagine and invent.

CN: Artificial intelligence is a matter of statistics. Of course it is capable of coming up with very efficient answers, but I wonder how far a solution that is «only» statistically correct can go today, compared to a solution that is also the result of human intuition.

NK: Exactly, this is the problem, not getting stuck in solutions that are correct, but mediocre. Moreover, it may become difficult to change points of view and thus propose different solutions from the standard, because many will think the same way. This is certainly a good reason to cultivate education and constantly improve our training.

CN: Looking deeper into your projects, what is your approach to selecting materials for structures?

NK: I don’t have a preference, each has its own specific potential. Any material can be used as long as it meets the structure’s requirements. Every material is interesting, but it is very complex to get to know its specific characteristics, as is the case with wood - which we use far too much today -, reinforced concrete, steel or composite materials.

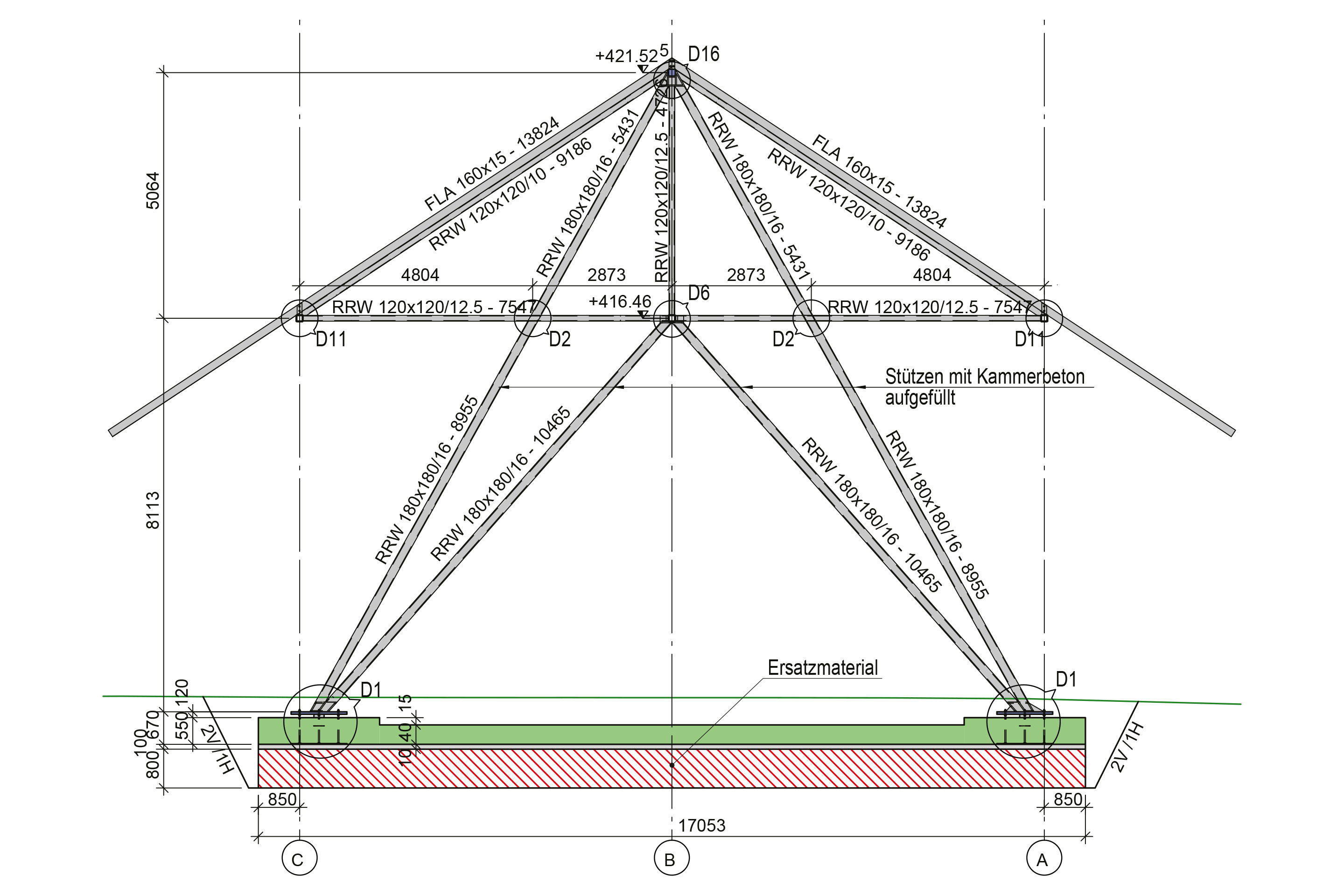

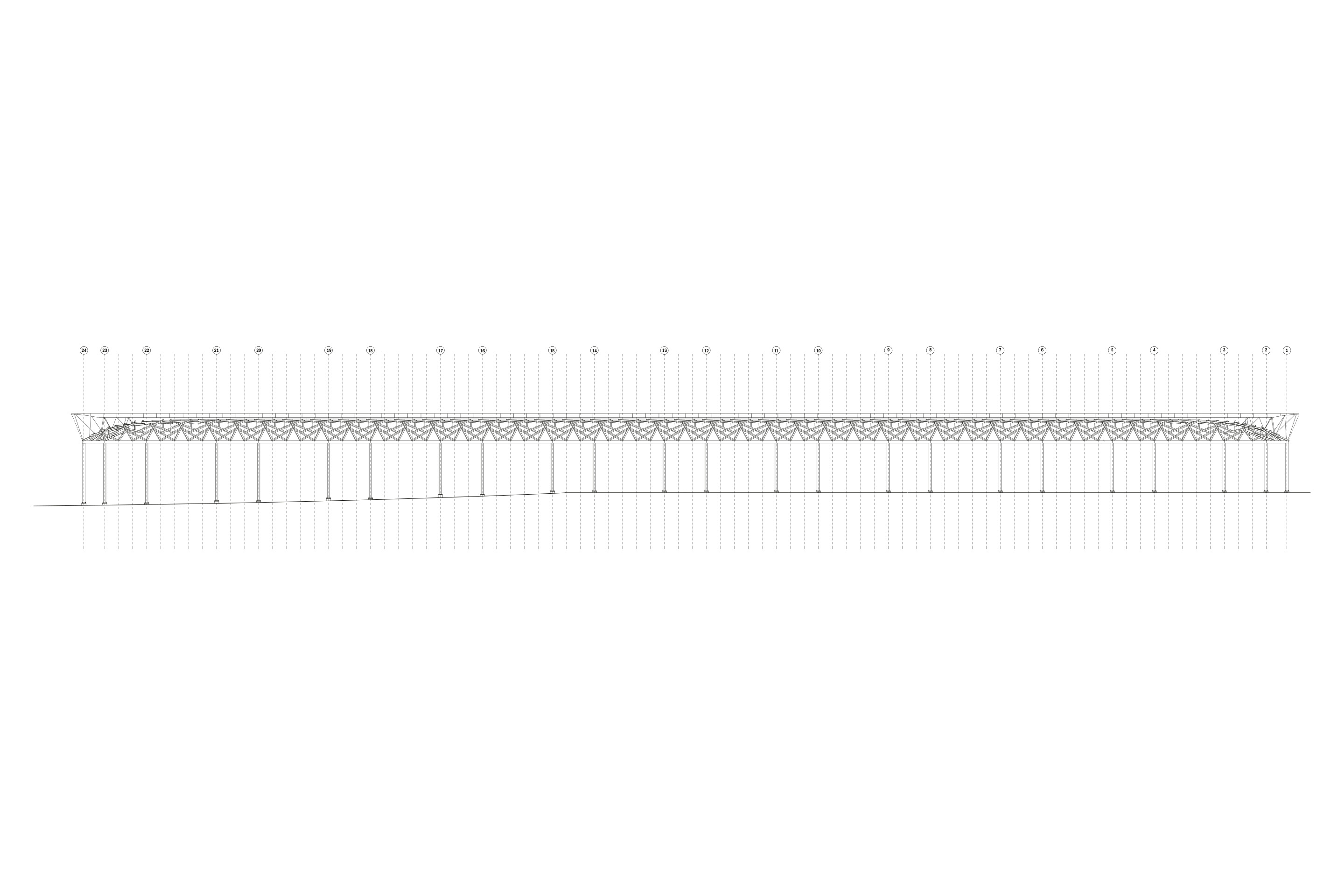

CN: In the case of the large canopy on the Koch Areal, why did you decide to use a steel structure?

NK: The project arose from the need to complete a very large existing canopy, which had been used for coal storage (Kohlenhalle) which had been partially demolished. This canopy is a real structural gem, supported by an extraordinary wooden structure, made of natural logs, with a structural span pushing the limit of the material’s possibilities.

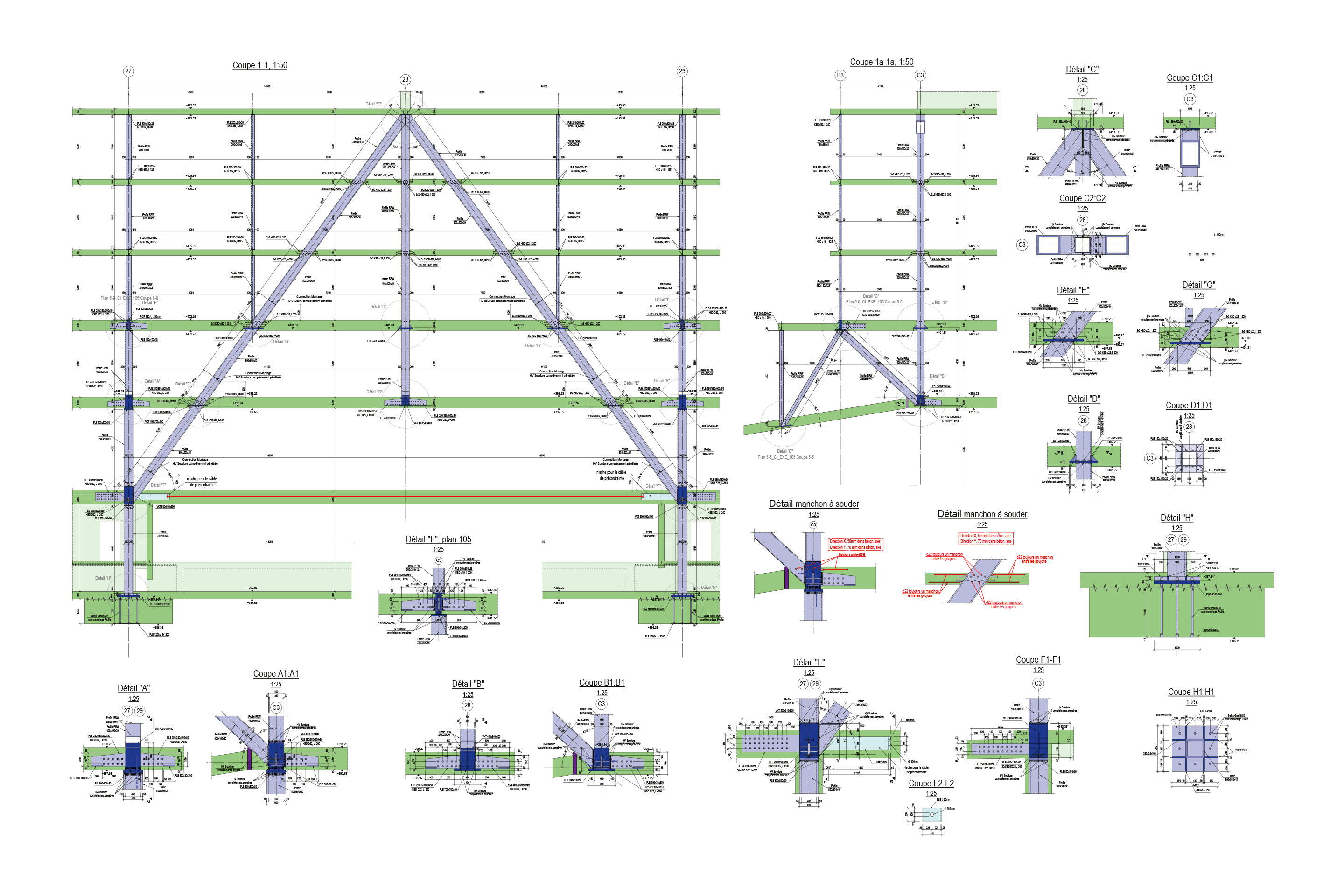

We were tasked to build the demolished part of the roof while keeping the ground space as free as possible. Initially we were asked to continue using timber for the structure, but the problem was that it would be too massive and heavy for the desired spans. So we proposed to build it in steel to achieve a comparable lightness to the existing structure. The old wooden structure is made of round trunks with a diameter of 220mm, while the steel profiles we used for the columns are 180x180mm, so when you look at them both in perspective they have the same section. The elegance of the design lies in the optimization of the new steel profiles’ proportions to match the dimensions of the existing wooden logs. If we had stuck to the ideology of using wood, the new elements would have been three times bigger and heavier.

CN: How do you compose and express the articulation of the assembly of the elements and joints you design? How do you develop the executive details?

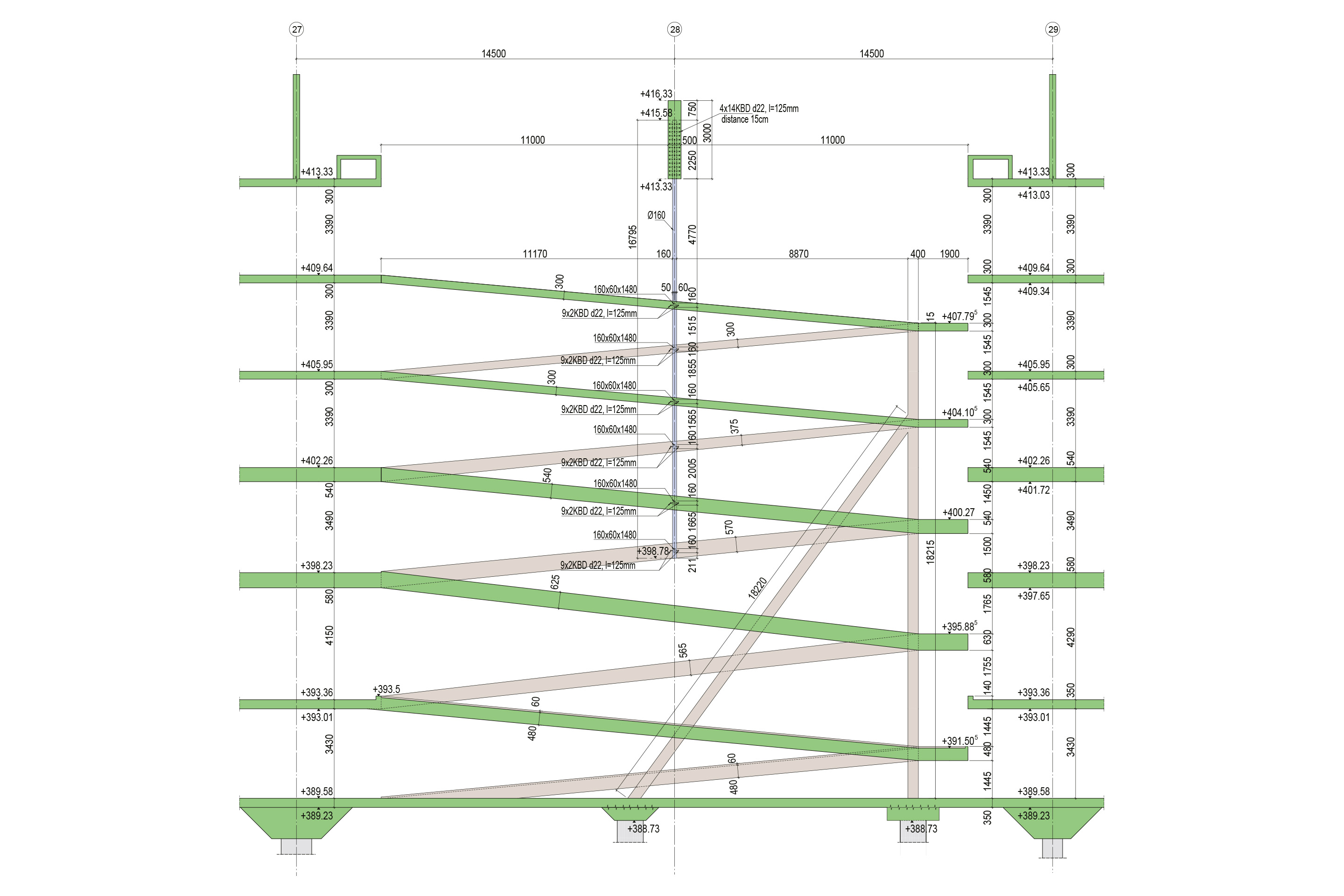

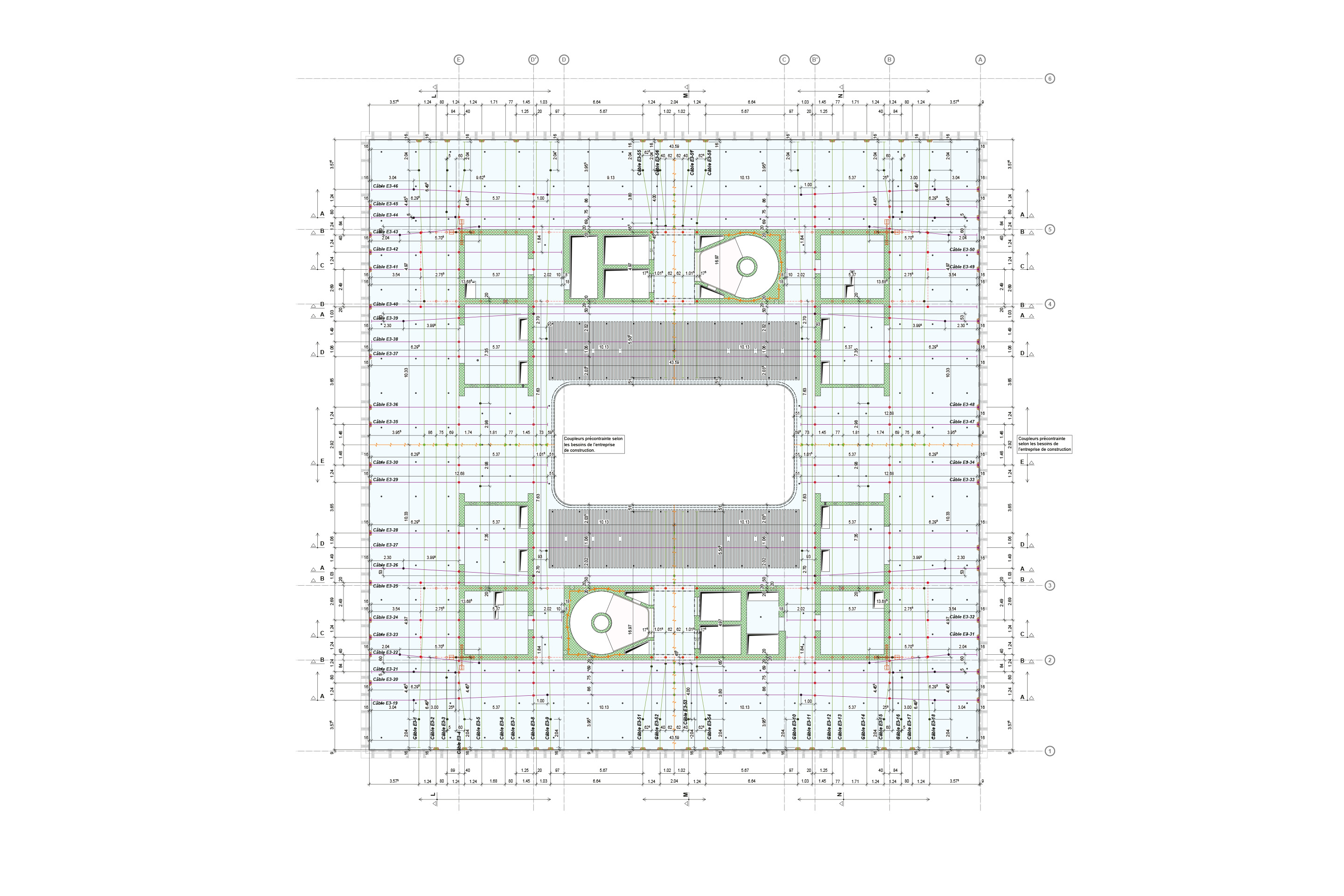

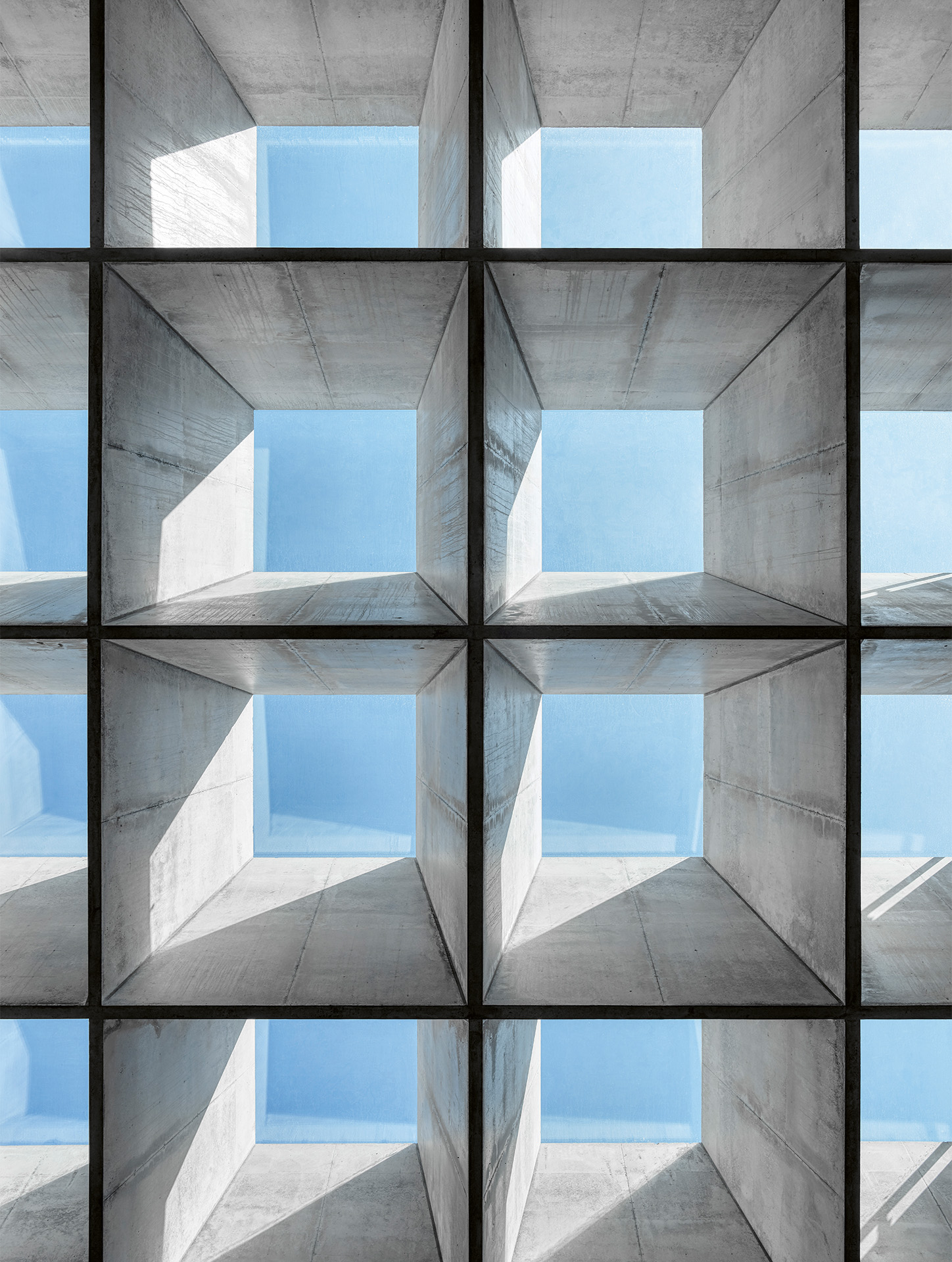

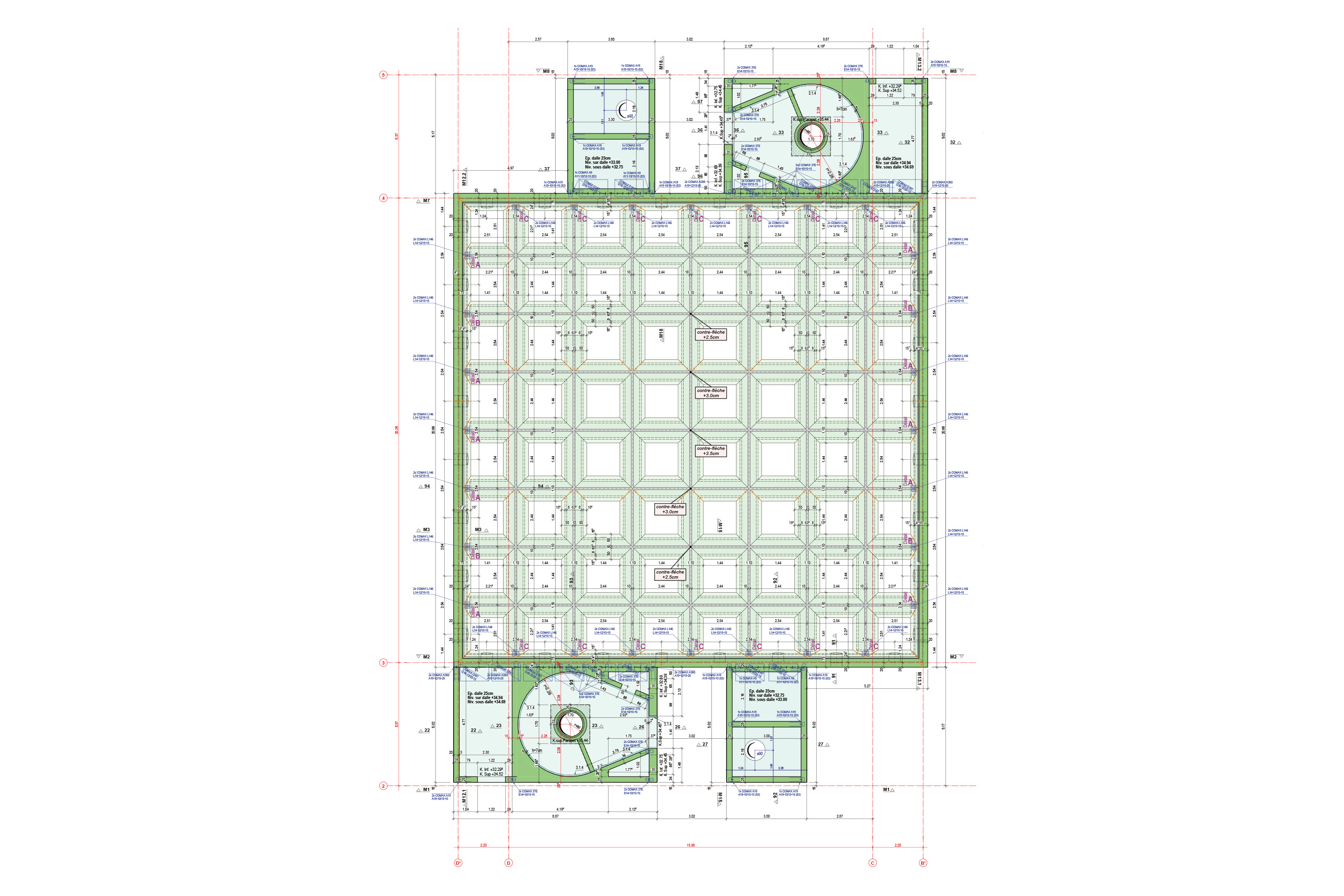

NK: The detail itself is a question of design, proportion, articulation, and therefore not just functional. It is very important to me that the details not only have a static function, but are also elegant and integrated into the structure. The more the detail expresses its structural function, the more interesting the result. In the case of the canopy at the Koch site, all the elements of the structure had to be had to be manufactured and partially pre-assembled in the workshop, then dismantled and transported, and finally assembled on site, always using the optimum material. The same appears for the HESAV building on the Campus Santé.

CN: In terms of design process innovation, is your office working in an interoperable BIM environment? What is your opinion on these tools?

NK: BIM was a trend ten years ago. I think it is not BIM in itself that is interesting, but 3D drawing. In our practice we draw everything in 3D, it is not always faster, but it allows us to see every aspect of a structure in more detail. So more than BIM, I am interested in three-dimensional design, which is also common in many studios today. When specialists work together today, in most cases they do not work in BIM, but projects are developed with non-interoperable specialist software and then information is shared, which is how it works in practice today. As far as 3D drawing is concerned, unfortunately many architects and engineers spend more time on general models than on the development of the project, especially in 2D plan and section. In my opinion, these 2D drawings, even if they are used by only a few people, are very important because they help to develop the design in the best possible way and to follow the construction with precision. They cannot be simple 2D prints of the general model, but specific drawings with all the necessary information, including details. In our studio, we spend a lot of time preparing these executive drawings; they are also a way of showing respect to those who will carry out the work. After all, you cannot demand excellence in execution if you do not provide the tools and information necessary to achieve it.

CN: Numerous international initiatives encourage a sustainable approach to design, such as the UN’s 2030 Agenda (2015), the EU’s New European Bauhaus program (2021), and the Baukultur Strategy currently being implemented in the Swiss Confederation (2023).

NK: With regard to the reuse of materials and building elements, I think that the discussions that have taken place over the past year are rather academic and I would like to see them become more practical, something that can really work. However, I find the topic very interesting and we have already tried to tackle it by participating in some competitions, such as the one for a pavilion in Basel by Areal Dreispitz or the one we recently won in Geneva, Parc de la Jonction.

For me, reuse does not mean reusing a window from another building, but that if we are serious about it, we must learn to construct buildings that are designed to be easily reused tomorrow. Unfortunately, this is still not the general practice; on the contrary, we continue to build buildings that require enormous amounts of energy and resources to achieve very modest results when they are next reused. It is therefore still logical to think about buildings that are designed to be easily reused over time. In the project for the Holliger Tower O1 in Bern (500-year tower), which I designed with the TEN studio, the structure is designed to last 500 years, while everything that is supported is designed and built to last 50-100 years, and then to be adapted or replaced. Again, this saves a lot of energy and resources because the structure does not change over time. For me, this is also a strategy for reuse. There is also the case of the completion of the large roof at the Koch Areal, where all the details are designed to be easily assembled and then dismantled, so that the materials and construction elements can be easily reused. Finally, there is the case proposed for the competition I made with Jan Kinsbergen for the recycled steel school in Zurich. It is interesting because we proposed a steel structure made entirely of reused elements, designed with joints that allow further reuse in the future. The structure is completely modular, made of the same elements and all of the same size. It must be said that in all these cases the economic aspects are always very important, you cannot improvise or cheat, because if you really want to be efficient. Economics is very honest, it immediately reveals the reality because it is directly related to the amount of energy you use.

CN: What is your opinion on the use of industrial prefabrication in construction?

NK: I can say that in Switzerland, for cultural and economic reasons, in-situ concrete still dominates the market. In general, however, I have nothing against it, as long as the structure is flexible and can be used in different ways in the future. So, in my opinion, there is still nothing more efficient than building a simple system of reinforced concrete columns and slabs, and then possibly reusing it many times. Companies in Switzerland can build these systems quickly and efficiently, and then the space can be easily reorganised and reused. Interesting times are coming, however, as many of the buildings constructed in this way in the 1950s and 1960s will now have to be adapted, renovated or reused at the end of their first service life, while retaining the structures.

CN: Thanks to the optimisation of the geometry of the elements, industrialised prefabrication offers different possibilities of expression compared to traditional on-site production systems. Before starting the interview, we talked about Mangiarotti’s architecture and how he works with the prefabrication industry to design parts that are optimised in terms of form and function.

As you know, prefabrication also allows you to better control production because you use processes where every aspect is optimised, such as production scheduling, material quality, temperature, humidity, curing times, finishes, etc.? Don’t you think it would be interesting to open up the Swiss reality more to advanced and/or industrialised prefabrication?

NK: I’m glad you mentioned Mangiarotti again because I’ve always liked his work and we have something in common: a passion for furniture, a family tradition and a personal hobby. I feel in tune with his thinking and I have to admit that there is something very interesting about his prefabricated systems. It is interesting that prefabrication allows better detailing, not only for aesthetic reasons, but above all because it is more efficient. It also allows for much shorter construction times, especially when building in the city.

In the case of the Holliger Tower O1 in Bern (500-year tower), for example, in order to be faster, we planned to produce the various building elements simultaneously in different factories and workshops. Saving raw materials is urgent, but not yet considered indispensable. In the future it will be, and as a society we will be pushed to save every resource, including prefabricating building elements so that they can be reused.

CN: In your experience, what role should the architect and engineer play in the design process?

NK: In construction, I have always respected architects as the first authors of the project. We engineers participate as second or third partners with the client, and then there is the builder, but that does not mean that we do not have an important contribution. I think it is always a team effort, even if the director is an architect. In the different projects my role can be very different, I have to be honest, sometimes I’m really just an engineer who calculates something that has to endure because there are countless other inputs from, for example, architects, but it has also happened several times that I’ve also made fundamental contributions to the development of the architectural project, and so I would say that in the end it doesn’t matter to make distinctions, what counts is the result.

So the engineer’s role in the design process can be the «standard» one, or it can be broader. At the end of the day, it is we structural engineers who can, in many cases, understand the engineering behind each profession’s contribution to a project.

CN: Finally, to conclude, what are your predictions and expectations for the future?

NK: I am not an engineer or a professional in the sense that the things I do or have done come from a wish or a dream. I don’t call myself a visionary and I don’t think I act like one. I would say that what drives me is more interest and passion for the work I do. The work gives me a lot of satisfaction and sometimes it doesn’t feel like work, someone said it’s my hobby and if I had the time and a long life I would be in the office for 100 years doing what I’m doing now. So we’ll see what happens, I hope we can still do something interesting for as long as we can.

Dr. Neven Kostic, ing. PoliMi, EPFL | drnk.ch