Elective affinities

Between art and architecture

In the essay by the co-urator of Archi | 02, the relationship between art and architecture is investigated through historical examples and contemporary projects in which the boundary between the two disciplines becomes porous. A journey between experimentation and public commissioning, collective vision and individual poetics.

Testo in italiano a questo link

Costantin Brâncuși’s assertion that «architecture is inhabited sculpture» not only accounts for the deep bond between architecture and art, but also opens up an infinite range of reflections which the variety of the works shown on these pages attempts to convey, rejecting any type of synthesis in order to instead encourage a sort of multiplication of viewpoints. This is not due to a purely classifying spirit, but to an intention to explore the countless possibilities that separate the rigor of Loos – according to whom «architecture is not an art, because anything that serves a purpose must be excluded from the realm of art» (Ornament and Crime, 1908) – from the ambition of Brâncuși to build one of his columns in Central Park in New York, containing apartments in which it would be possible to live.1 Aware that the issue is not to consider the so-called utility of art, nor to cast doubt on the implicit correspondence of architecture to its use, it is still impossible to overlook the ways in which the relationship between art and architecture takes on substance, and we can identify various occasions thanks to which this bond takes form.

If we refer to the historical panorama and Swiss legislation, it is easy to identify a series of examples and modes of intervention that can be termed traditional, we might say, attributable to the so-called Kunst am Bau. Observing the current condition, we are faced with a variegated phenomenology, within which the relationship between art and architecture becomes more complex and much less defined and definable in terms of offspring, ancestry or prevalence.

In the wake of the synthesis of the arts formulated by modernism, starting from the second half of the 20th century, and of a series of actions previously undertaken, the practice of Kunst am Bau has taken form, seen as a tool of promotion for artists and support for culture; thanks to the so-called «Per Cent For Art» the examples of interaction between the arts have multiplied, exploiting the opportunity offered by the wording of the law calling for specific funding earmarked for the production of works of art in the context of construction projects financed with public resources.2

According to Visarte, the association whose mission is to represent the interests of visual arts professionals in Switzerland, «art in architecture and public spaces is not a superfluous luxury [since it] grants an emotional dimension to the functional context of the constructed environment, making a significant contribution to quality of life and our sense of identity.» Furthermore: «the artwork completes the work of architecture and the context, endowing them with meaning. It prompts curiosity, stimulates perception, broadens our outlook on the world and proposes new relationships and new meanings».3

In tune with what is asserted by Visarte, for a long time the practice of Kunst am Bau has made it possible to create works of art conceived for specific architectural and urban situations, with results of remarkable quality. Nevertheless, over the years – due to a series of factors of an economic and procedural nature – there have more frequently been artistic projects that take a secondary position with respect to the architectural host; not fully integrated, also because they are often installed when the construction is already finished, these works have been the victim of a sort of downgrade, to the point of often transforming into removable decorations, extraneous in some ways to the architectural space itself.

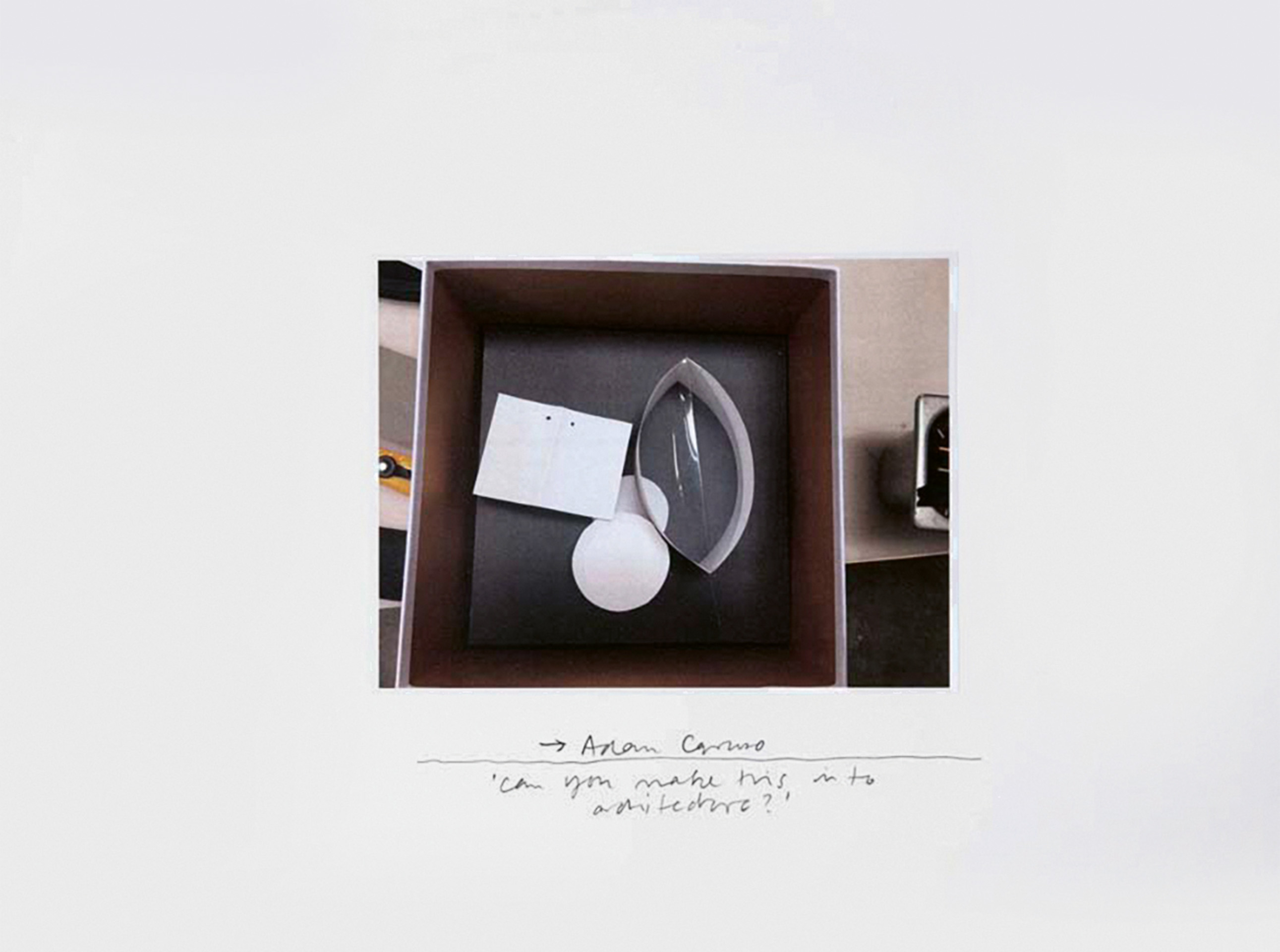

Perhaps for this reason, recently projects of a different type have come into favor, with the aim of putting art and architecture on the same plane, avoiding any sort of hierarchy: a trend that at least informally opts for «Kunst und Bau» (or «Kunst im öffentlichen Raum») over Kunst am Bau, and one where the use of the coordinating conjunction excludes (at least conceptually) relationships of subordination that function merely to fulfill legislative dictates, putting the focus on the idea that art and architecture are dependent on each other. In this sense, to debunk several false beliefs and to open the way for the enumeration of possible interrelations we are trying to bring to the fore, it will suffice to mention certain collaborations between artists and architects, such as that of Helmut Federle with the studio Diener & Diener for the Swiss Embassy in Berlin, or the Novartis Building in Basel, and the very fruitful cases in which art has become an effective seismograph, urging architects to look farther beyond and to foresee themes that have not yet become part of the practice of construction.

Inside this circularity – new in certain ways, but with ancient roots – the quota and role of each discipline, the extent to which they depend on each other, their expressive autonomy and which terms of interpretation would be necessary to use in order to put these intersections into focus, ought to be analyzed work by work, project by project. Nevertheless, to clarify the field we are trying to penetrate it is useful to recall what Anthony Vidler asserted in 1999: «Artists, rather than simply extending their terms of reference to the three-dimensional, take on questions of architecture as an integral and critical part of their work in installations that seek to criticize the traditional terms of art. Architects, in a parallel way, are exploring the processes and forms of art, often on the terms set out by artists, in order to escape the rigid codes of functionalism and formalism. This intersection has engendered a kind of “intermediary art”, comprised of objects that, while situated ostensibly in one practice, require the interpretive terms of another for their explication».4

All this pertains first of all due to the many similarities between the compositional processes belonging to the arts and architecture, but also due to the sharing of many tools, such as – for example – the model and the practice of reproduction of objects, which precisely because of the disorientation produced by the process of reduction or enlargement of scale can change value and trigger new relationships of meaning. With respect to this mode of action and its results, meaningful examples include the Assemblages of Clare Goodwin, which recombine architectural elements to give rise to unexpected situations and meanings, or the work of the Zurich-based art duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss, who through the various versions of that strange object they call Haus 5 enact a spatial (even urban), prior to architectural, reflection on the relationship between size, position, character and perception: with Haus «the “abstract” art of architecture thus becomes the “figurative” subject of sculpture».6 It speaks to architecture about its intrinsic characteristics, the monotonous familiarity of common – if not «unspectacular» – buildings, and their inextricable relationship with the city they contribute to construct. On this theme, Stanislaus von Moos remarks: «whether as architectural “project” or as “sculpture”, Haus, like the stroke of a gong, took possession of the “no-man’s-land” between architecture, urban planning, and sculpture. And it did so at the very moment when that realm began to take an interest in art».7

We can examine projects that move in this direction in order to probe – starting from art or architecture, either one – into territories in which the overlap between the disciplines become explicit, and the intersections take concrete form in works, observing the extent to which experiences of this type are increasingly nurturing a clearer experimental dimension of architectural practice, probably influenced by the research of Austrian origin that seeks to formalize spatial, political, social and cultural reflections, relying on a mutual semantic exchange.

The aim is thus to overturn the conviction that art exists in a secondary condition with respect to the solid body of architecture, and to sustain the much more unstable but no less relevant hypothesis that the more or less ephemeral strategies and tools utilized by the art of the last century are proving to be more capable than architecture itself of reinterpreting architectonic codes and the urban context, and as a result of having a more active influence on reality. Art has become a location of essential consideration for architecture, at least since architecture has become part of the sphere of interest of artists, or more precisely since artists have begun to consciously and explicitly utilize architecture and the city as a support – not only physical – for their work.

Getting back to the concept of «intermediary art» as formulated by Vidler, and overlaying it with reflections generated by starting from the statement of Richard Serra, according to whom «architecture in not art! [Because] art is purposely useless. And that’s what makes it more free than buildings»,8 everything seems to get complicated to the point of deadlock. Commenting on the reactions after the construction of the Bilbao Guggenheim designed by his friend Frank O. Gehry,9 Serra, goaded on by Charlie Rose, ventures into considerations that would seem to be in opposition to the position of Vidler: «If you analyze what I said, I didn’t take a public slap at Frank. I said that art is purposely useless, that its significations are symbolic, internal, poetic – a host of other things – whereas architects have to answer to the program, the client, and everything that goes along with the utility function of the building. Let’s not confuse the two things. Now we have architects running around saying, “I’m an artist”, and I just don’t buy it. I don’t believe Frank is an artist. I don’t believe Rem Koolhaas is an artist. Sure, there are comparable overlaps in the language between sculpture and architecture, between painting and architecture. There are overlaps between all kinds of human activities. But there are also differences that have gone on for centuries. Architects are higher in the pecking order than sculptors, we all know that, but they can’t have it both ways».10

Apart from any agreement with Serra, this is precisely the issue: «wanting to have it both ways!». Not so much in authorial terms as in disciplinary terms, something that might sound contradictory, but which Vidler explains very well, identifying an increasingly widespread trend that endorses not the individual work (be it artistic or architectural), but the desire to reflect on processes, procedures and transcriptions, capable of nourishing from within (and often also from outside) the disciplines, their contents and, as a result, their languages, in absolute awareness of the fact that every technique has its own aesthetic (and vice versa), which cannot (and must not) be overlooked.

During the course of the 20th century and even more so at the start of the new one, art and architecture have augmented their level of problematics; this has produced a sort of gray zone in continuous growth, which contains many of the experiments of greatest interest, which while they offer a representative cutaway view of new tendencies, raise the problem of the status of collaboration between the parties involved.

In 1982 Paolo Fumagalli wrote: «In the most fertile moments of their relations, it is hard to distinguish where the work of the architect ends and that of the artist begins».11 What is clear is that the point of contact between art and architecture requires a process of continuing redefinition: on each single occasion, it shifts towards one or the other discipline, often without demanding a clear distinction of the field, at least when it comes to the interests and concerns of artists and architects.

Taking this complexity into account, we cannot refrain from asking ourselves if it is necessary to establish a distinction between the two domains, or to lay claim to their respective autonomy. In keeping with a positive response, we could start over from Loos and Serra; otherwise, if we admit that the task is not to identify boundaries or zones of expertise, but to bear witness to this new free zone and the infinite possibilities offered by working inside it, we will have to attempt to describe the formal, spatial and social phenomenology that is being produced.

Therefore the issue is to attempt a reckoning of the increasingly complex range of cases in which the relationship between art and architecture is being interpreted, with a particular focus on the movable boundary that in many instances is established between the world of art and that of architecture, and vice versa, without forgetting that the relationship between art and architecture is also a human relationship, that does not reach an end in the works, but starts from them to produce cognitive paths spanning the disciplines. This becomes clear if we re-read the well-known The Art Museum of My Dreams or A Place for the Work and the Human Being (1986) by Rémy Zaugg in the light of several projects by Herzog & de Meuron, or if we think about the influence of Zaugg and Joseph Beuys on their work. Analogies of this type can be found in the collaborations – stable, in some ways – between architects and artists, such as the ones between Caruso St John and Thomas Demand, EMI Architekt*innen and Christian Hörler, Livio Vacchini and Livio Bernasconi, or the fertile relationship between Peter Märkli and Hans Josephsohn. The list could be almost infinite, but mention of the drawings by Märkli can suffice to clarify how art often becomes a place of essential reflection for architecture, because it enables deeper knowledge of human and architectural space. In fact, «looking at the drawings, we notice that Märkli’s buildings, otherwise uninhabited, often play host to sculptures by Josephsohn, which come to terms with the architectural elements, measuring them, at times defining them by filling up openings, stopping a corner, underlining the upward closure. Sometimes they become architectural elements themselves, with their materiality and roughed out forms, columns, capitals. Among the most recent drawings, the lengthened, slender figures of Giacometti linger in front of a façade, stretching to the point of surpassing the height of the possible building, and become a niche, transforming into something else. Sculpted human figures seem more effective than abstract proportional silhouettes to grant life to these works of architecture, in Märkli’s research.12

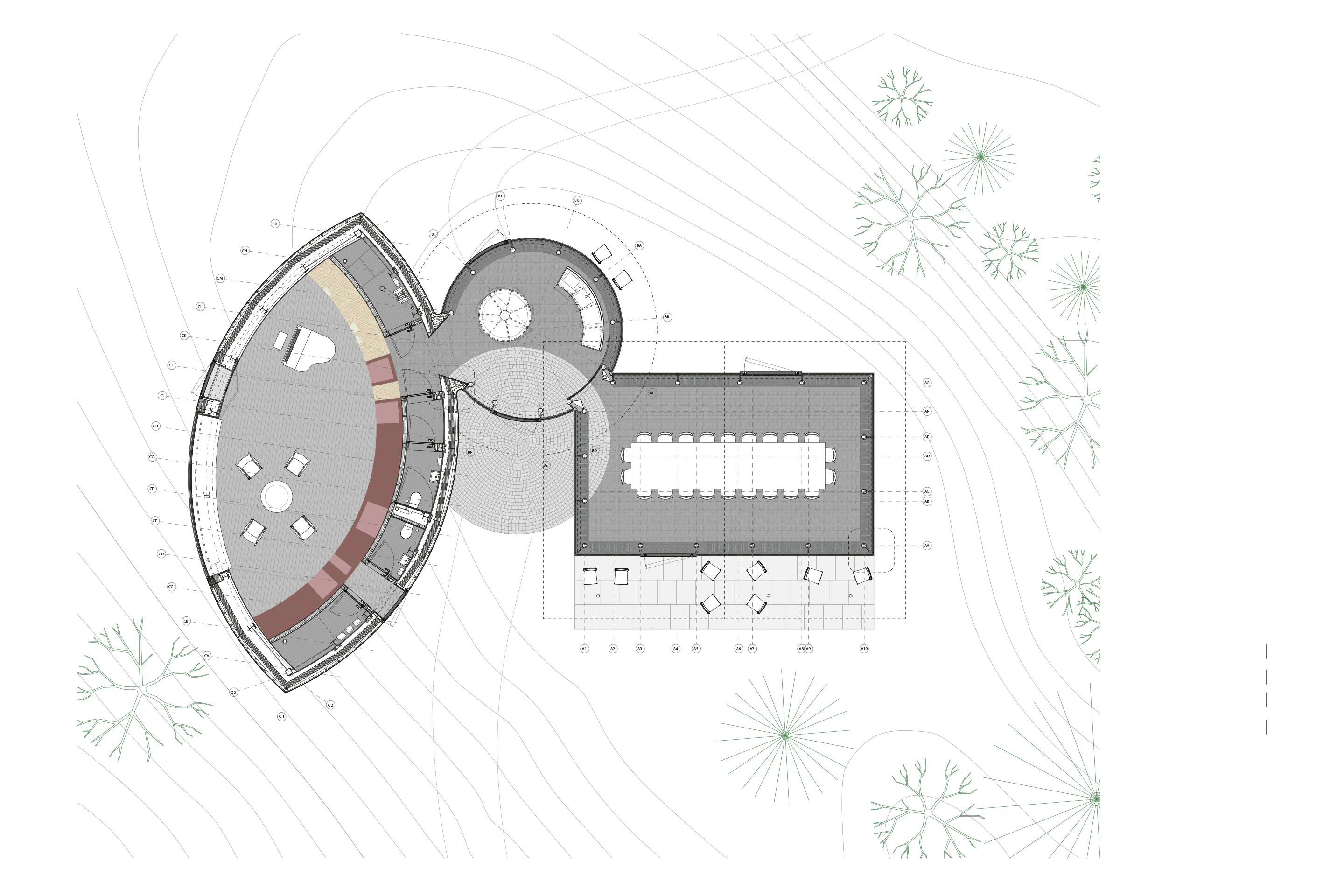

In other cases the art, pretending to be the physical support of the architecture, becomes its conceptual support: Unverrückbar oder: Die Kunst der entscheidende Anfang von etwas sein / Inamovibile ovvero: L’arte può essere l’inizio decisivo di qualcosa by Eric Hattan in the new atrium of the St. Jakobshalle in Basel by the architects Jürg Berrel and Heinrich Degelo plays with disorientation and sets out to demonstrate that precisely like the first stone «the art places itself at the beginning of the architecture, and is not a second thought at all».13 A gigantic boulder of 25 tons is positioned at the base of the single pilaster of support for the roof of the foyer. The reaction of the boulder to the forces was unpredictable, and therefore the structural statics could not be determined in a traditional way; furthermore, the architects wanted the pilaster to be tapered towards the bottom. Everything alludes to an overturned column with an ancestral stone capital, apparently unstable and unusual, and this happens thanks to the structural solution proposed by the engineers Schnetzer Puskas, who have hung the stone on the column by means of a steel beam that crosses the concrete support and the boulder with a steel beam, connecting them. In turn, the beam rests on a steel vat set into the terrain.14

This is one of the cases that should be mentioned, because apart from any consideration of a formal character, and perhaps apart from the (artistic or architectural) results, it resonates with the statement of Donald Judd, who said «everyone wants to treat art and architecture as a matter of taste, when I want to consider it as a matter of knowledge.»15

Note|Notes

1. «I would like to make my column in Central Park. It would be greater than any building, three times higher than your obelisk in Washington, with a base correspondingly wide – sixty meters or more. It would be made of metal. In each pyramid there would be apartments and people would live there, and on the very top I would have my bird – a great bird poised on the tip of my infinite column». F. Merrill, Brâncusi, the Sculptor of the Spirit, Would Build ‘Infinite Column’ in Park, in «New York World», 3 ottobre 1926 [TdA].

2. The first federal resolution for the promotion of the arts dates back to 1887; in 1950 it was decided to enhance public buildings by allocating 1% of the construction costs to the creation of works of art, in analogy with other foreign programmes such as the well-known US ‘art-in architecture’, or similar measures taken in France, Germany and Italy.

3. Cfr. https://visarte.ch/it/arte-nellarchitettura/

4. A. Vidler, Warped Space: Art, Architecture, and Anxiety in Modern Culture, The MIT Press, Cambridge MA 2000, p. vii [TdA].

5. PWith regard to the description of this work and the role it played in the cultural context within which it was conceived, please refer to Philip Ursprung’s description.

6. S. von Moos, Peter Fischli, David Weiss: Haus, Walther König, Köln 2020, p. 12 [TdA].

7. Ivi, p. 13 [TdA].

8. R. Serra, Art and Design. Talk with Charlie Rose, 14 dicembre 2001, min. 43.46 e seguenti [TdA], cfr. https://charlierose.com/videos/18060

9.It is important to remember that for the wing specially designed by Gehry for Serra’s works (the so-called ‘boat gallery’), the expressive architecture of the Canadian tried to take a step backwards, so that the spatiality of the Californian artist’s works could be fully celebrated: in this case, the architectural gesture is at the service of the futility of art.

10. Quoted in C. Tomkins, Lives of the Artists: Portraits of Ten Artists Whose Work and Lifestyles Embody the Future of Contemporary Art, Henry Holt and Company, New York 2008, p. 73 [TdA].

11. P. Fumagalli, L’opera d’arte nell’architettura, in «Rivista Tecnica», n. 7-8, 1982, p. 22.

12. M. Maguolo, Tracce visive di pensiero. Presentazione di Peter Märkli Dessins, in «La Rivista di Engramma», n. 207, 2023, p. 119.

13. From the Press Release of the Department of the Presidency of the Canton of Basel-Stadt, settembre| september 2017, cfr. https://www.hattan.ch/fileadmin/hattan/user_upload/PDFs/Kunst_und_Bau/2014_EH_St.Jakob_Doku.pdf.

14. Cfr. First the Stone, film di Severin Kuhn, 2018, https://www.degelo.net/projekte/intervention-ix.php.

15. Note titled «15 luglio 1987, 101 Spring Street», in D. Judd, Donald Judd Writings, a cura di| curated by F. Judd, C. Murray, Judd Foundation/David Zwirner Books, New York, p. 472 [TdA].