Between two acts:

"inhabiting" and "living" the house

Testo in italiano a questo link

In his lecture L’uomo e la sua casa (March 1987) at the seminar La Torre di Carl Gustav Jung, Renato Boeri identified as essential qualities for the construction of one’s own home «respect, in its structure, for love, sexual life, and individual privacy even within the family context», alongside the capacity to guarantee «for each person (…) the greatest freedom compatible with others’ freedoms, for man is condemned to be free, and the home must be a refuge, not an exile, a starting point rather than a barrier to action». Cini Boeri also spoke at the seminar, outlining the rationale behind the Bunker House project (1967), realized two years after the end of her relationship with Renato: «Twenty years ago I was trying to rebuild my life with my three children, a life founded on mutual support and respect. The result was a centrally planned house, a tent set upon the rocks (…)»: built with essential materials, it embraced the roughness of the terrain, supporting individual desires, family relationships, and the surrounding landscape.

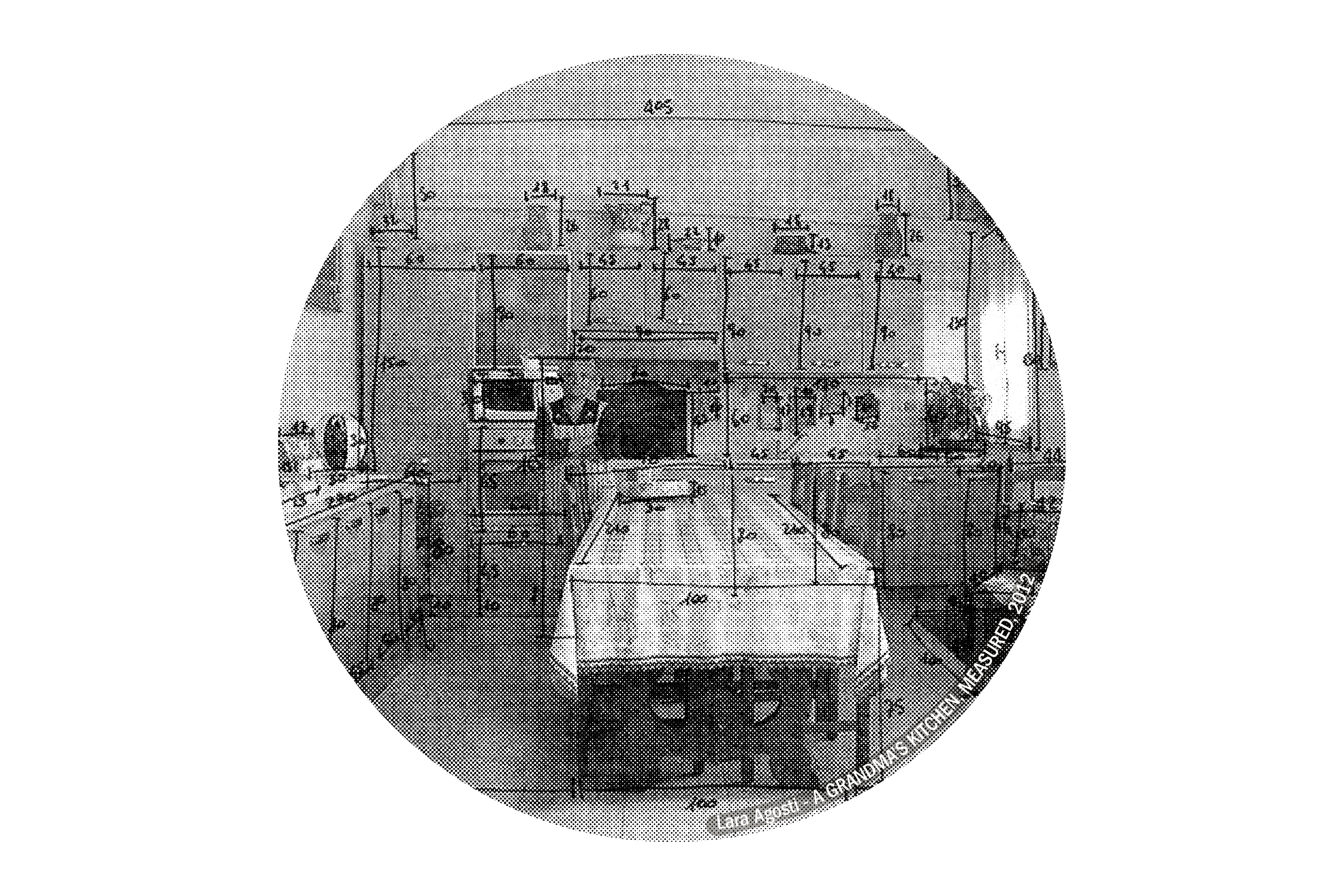

The Bunker disrupted the conventions of the bourgeois home, questioning the spatial and formal norms of the era and eschewing functional definitions of rooms in favor of a psychological dimension: the kitchen as a room of «shared commitment», the living room for «creative dialogue», followed by rooms «of love», «of dreams, and «of personal hygiene».

These observations resonate, amplified, in Maria Shéhérazade Giudici’s essay Counter-planning from the Kitchen (2018): the author dissects the typology of the home, showing how living rooms, kitchens, and separate bedrooms express a stereotypical social diagram, and proposes design and theoretical strategies to re-signify domestic spaces beyond inherited models.

The single-family house remains a privileged space for experimentation, where individual desires and evolving needs for comfort and sociability can be recognized. Architecture can still respond meaningfully to these questions, redefining its design vocabulary. The paradox is evident: while contemporary debate challenges the home’s economic and social model, the discipline still finds in housing a significant field in which to investigate ways of living and perceiving space. The focus, therefore, should shift toward the «domestic condition» rather than the «standard house»: within this framework, expressive freedom in spatial composition, room proportions, and the human and physical relationships made possible by the home becomes central.

The examples presented show «homes to inhabit and live with», reflecting on spatial composition as a tool to understand and transform contemporary living. One question remains open: should all of this remain confined to individual experimentation? It would be a mistake to dismiss these projects as «elitist luxuries»: the history of innovation demonstrates that the most radical insights often emerge in protected contexts, only to later become shared design heritage, capable of influencing collective ways of living.