The Silence and the Light: Erik Gunnar Asplund’s Göteborg Courthouse

At the Röhsska Museet in Göteborg, the retrospective Asplund och rådhuset (27 September 2025–30 August 2026) has brought to light previously unpublished materials on the extension of the courthouse, offering new ways of understanding one of the longest and most complex episodes in Swedish modern architecture.

Testo in italiano al seguente link

In the spring of 1913, when he won the competition for the extension of the Göteborg Courthouse, Erik Gunnar Asplund (1885–1940) was twenty-seven years old; in the winter of 1937, when his work was finally completed, he had only a few years of life remaining. Therefore, the story of this building becomes intertwined with the entire artistic trajectory of the most influential Swedish architect of the twentieth century and with the slow transformation of the country’s architectural culture. During the quarter of century, Asplund’s language changed radically: from an austere national romanticism, through a measured, «civil» Nordic classicism, to a mature yet at the same time «hesitant» functionalism that sought to question the «dogmas» of the Modern Movement from within. The Göteborg Courthouse extension, added to the complex designed by Nicodemus Tessin the Elder (1615–1681) between 1669 and 1672 and implemented over the centuries, thus becomes the theatre of a long evolution which is not only stylistic, but also—and above all—ideological.[1]

At the end of the nineteenth century, as the city expanded rapidly, Göteborgs rådhus—in which both the town hall and the court were housed according to the Swedish custom—had become far too small to meet the needs of a growing urban centre. For several decades there was debate over whether to demolish or extend it; the «courthouse question» (Rådhusfrågan) occupied local politics until 1912, when the municipality launched the competition for the reconstruction and enlargement of the building facing Gustaf Adolfs Torg. Among the thirty-one entries submitted, the young Asplund won first prize with a scheme bearing the motto Andante: a title that is not a mere musical flourish but a declaration of method, an invitation to conceive the new building «at a human pace», following a calibrated and harmonious rhythm. Although still anchored in a language of the past, the project made a radical move: it eliminated the monumental entrance towards the square and rethought the access from the canal side (Stora Hamnkanalen),[2] the old temenos of the city. The architect explicitly stated that he did not consider the nineteenth-century façade to be binding. Indeed, he aimed to refound the complex from within, according to a modus operandi that began with spatial sequences and plans and only at the end arrived at the elevations, conceived as the ultimate outcome of the design process.[3] The 1912–13 competition marked the beginning of an «endless» saga: variants, counter-proposals, renewed discussions—some of them conducted in parallel with the project for the redesign of Gustaf Adolfs Torg (1916–17)—up to the still-classical projects of 1925 that were finally supposed to be realised. The objective was clear: to integrate the historic building and the new wing into a single organism. What remained unsolved, however, was the «political» problem of the façades, torn between preserving the historic image of the town hall and the desire to introduce an updated architectural language.

In those same years, Asplund became a central figure in Swedish architectural culture thanks to two works that brought him to the attention of a wider public: the Stockholm Public Library (Stadsbibliotek, 1918–28), a manifesto of clear, measured classicism, and the Woodland Cemetery (Skogskyrkogården, 1917–40), designed together with Sigurd Lewerentz (1885–1975), which would become one of the most influential sacred landscapes of the twentieth century. Alongside these buildings came increasingly significant public commissions, culminating in his appointment as chief architect for the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition (Stockholmsutställningen). Such opportunity enabled Asplund, under the artistic direction of Gregor Paulsson (1889–1977), to complete his passage towards modern architecture. The exhibition and the book-manifesto acceptera, written with the other protagonists of that season, marked his firm adherence to functionalism. acceptera «does not have the utopian ambitions and aggressive rejection of history of other avant-garde manifestos, but instead proposes a modern recovery of the past»;[4]in one of the chapters attributed to Asplund—The Old and the New—the architect defends the value of historical stratification and talks about respect for the scale, the proportions and the colour of the city, while rejecting stylistic imitation.[5] Modernising tradition without erasing it, accepting the historical reality of the context and making it the living matter of the project: those are the questions lying at the heart of the Göteborg Courthouse extension.[6]

The momentum in the project came not from changes within the administration, but rather from a shift in the broader context: the economic crisis of the early 1930s and the action of the new Social Democratic government led by Per Albin Hansson (1885–1946), in office from 1932, resulted in the launch of an ambitious Keynesian public works programme.[7] Thanks to these funds, the city of Göteborg could finally return to the long-standing Rådhus desiderata: it was decided to demolish the former commandant’s house nearby the building and to reconstruct in its place the new wing for the district court (Göteborgs tingsrätt). The 1925 project was taken as a starting point, with the awareness that in the meantime a decade had passed and the context had changed profoundly. Asplund himself was no longer the same architect: over the years he had progressively renewed his style, until he had «made the transition to the Modern Movement on his own terms».[8] In this process—in which Asplund’s modernity reflects the altered political climate—a decisive role was played by the presence, from 1932, of Uno Åhrén (1897–1977), the youngest of the co-authors of acceptera, who was appointed chief architect of the municipal planning office, housed in the town hall itself. From this position—at the crossroads of politics, planning and architectural culture—he was able, through a silent yet decisive influence, to steer Asplund’s project towards a more clearly modernist language, in tune with the social and judicial reforms pursued by the Social Democratic government.[9] The Göteborg Courthouse thus emerged as an eminently political building: the product of a stimulus plan, desired by a city council with a Social Democratic majority, built at a time when the very conception of justice was changing, from punishment to rehabilitation, from an obsession with guilt to the centrality of the individual.[10]

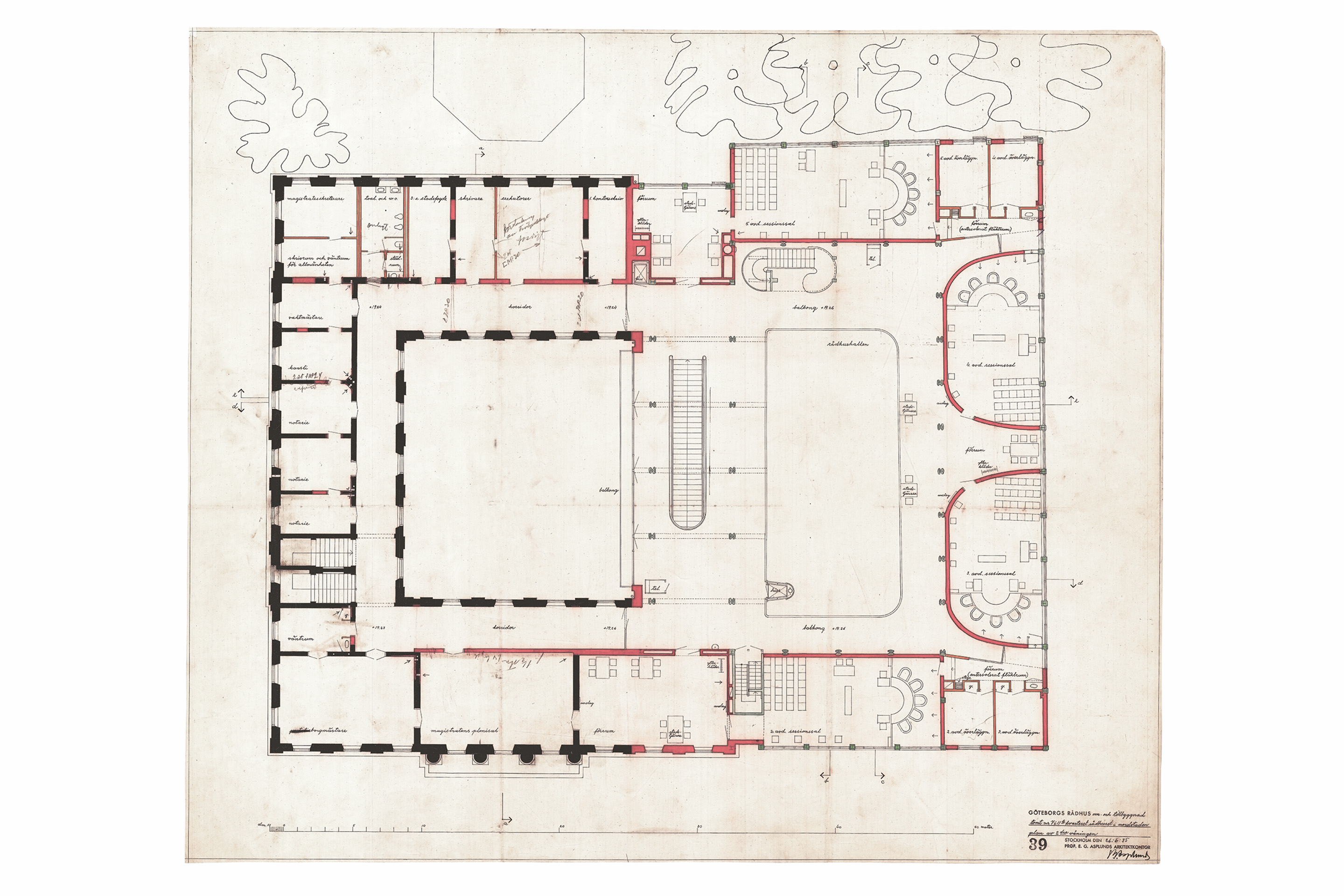

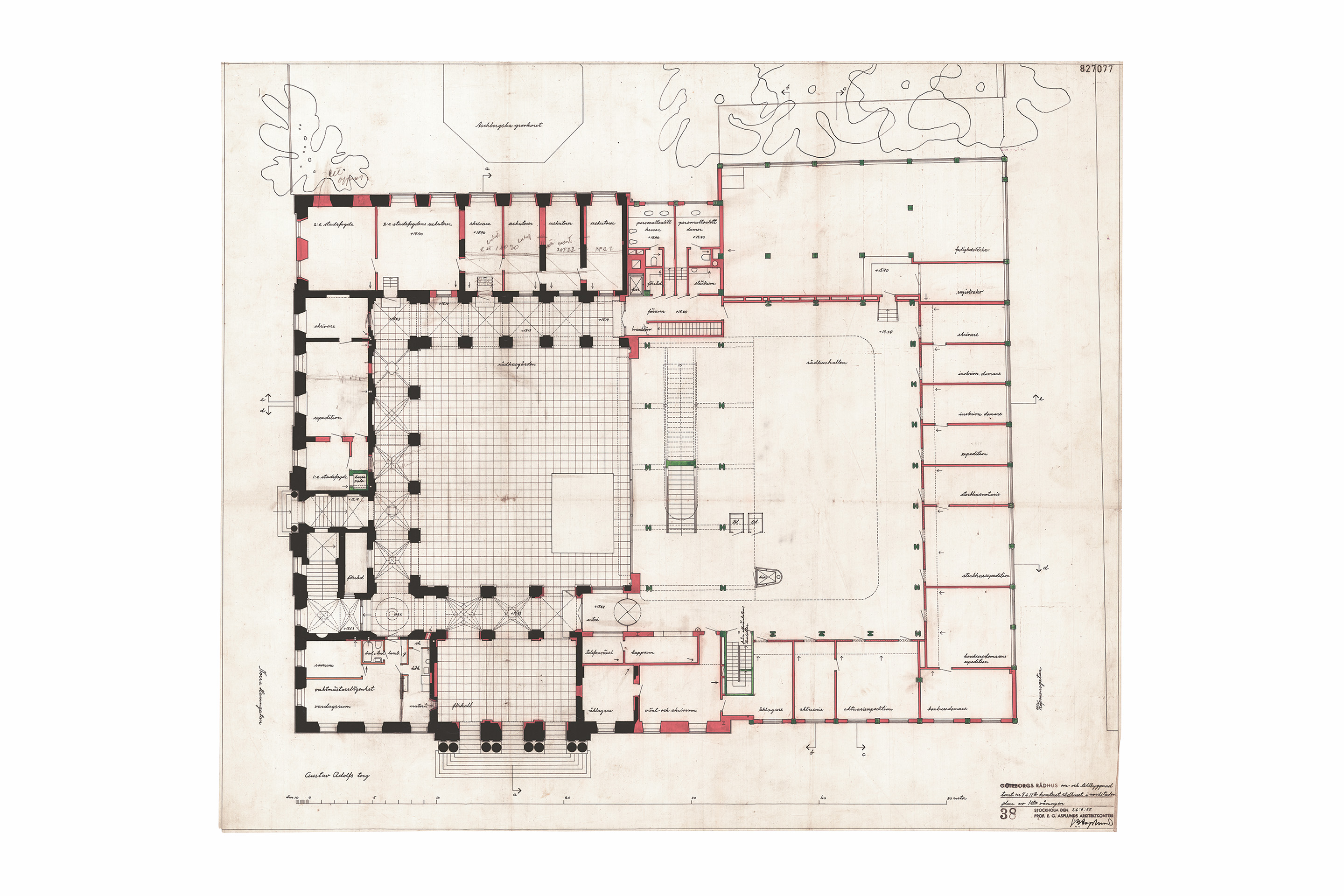

When the construction site reopened in 1934, Asplund was a well established architect and, since 1931, professor at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm (Kungliga Tekniska högskolan), the institution from which his young collaborators—often still students—were drawn. Initially, Asplund sought a cautious solution for the façade: a sort of «controlled pastiche» that prolonged the neoclassical language of the town hall, while inside he was already imagining a modern structure of steel, glazed walls and a large entrance hall, the «salle des pas perdus».[11] According to the account of one of his students, when pressed by the young functionalists who urged him to adopt a radically new façade, the architect replied: «here, our contribution will be on the interior».[12] Yet it was precisely the work of these young architects that undermined that defensive attitude. Testimonies attribute the design of the realised façade to Tore Ahlsén (1906–1991): an abstract grid with off-centre windows, recalling the contemporary proposal for the student club (Stockholms nation) in Uppsala of 1936.[13]

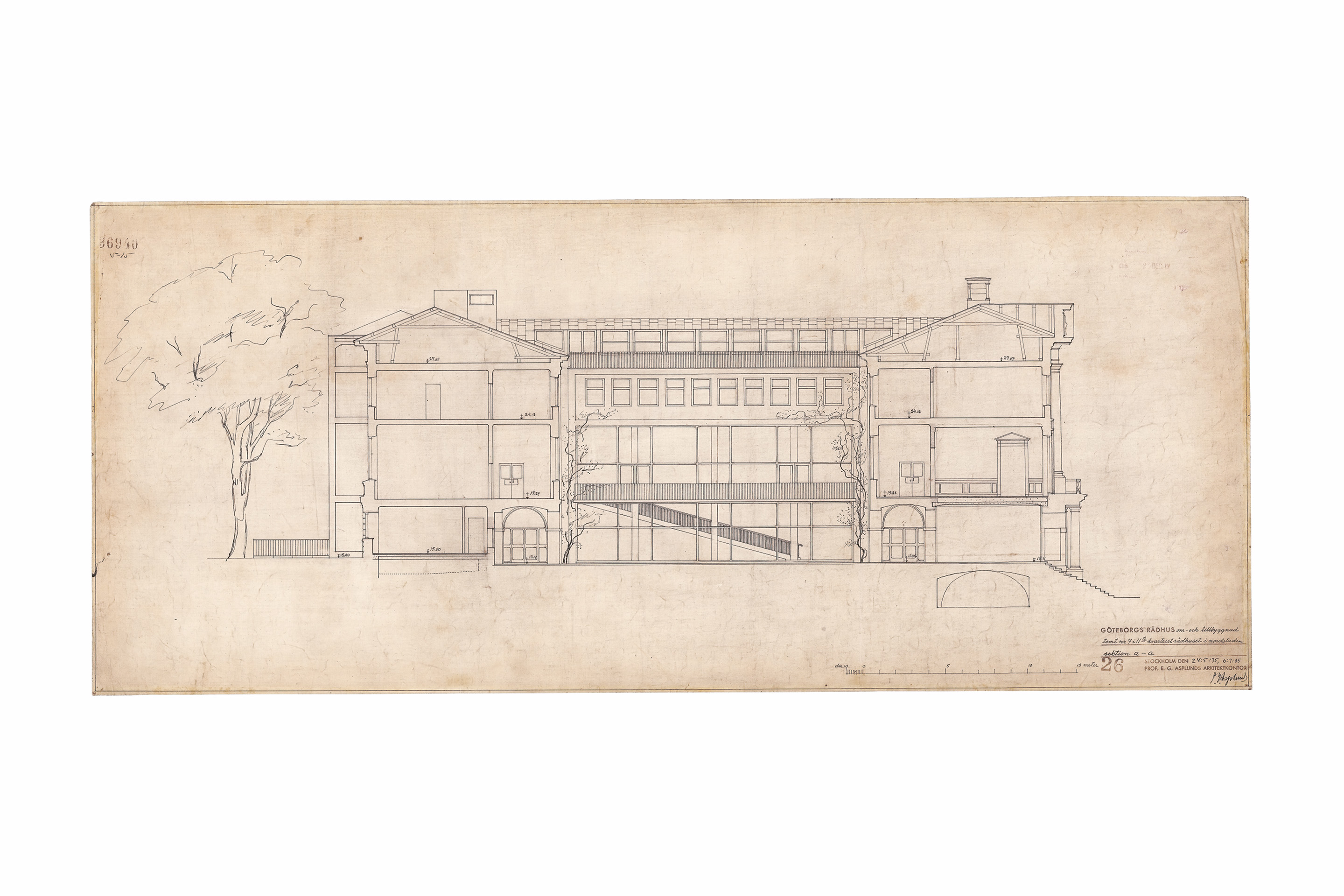

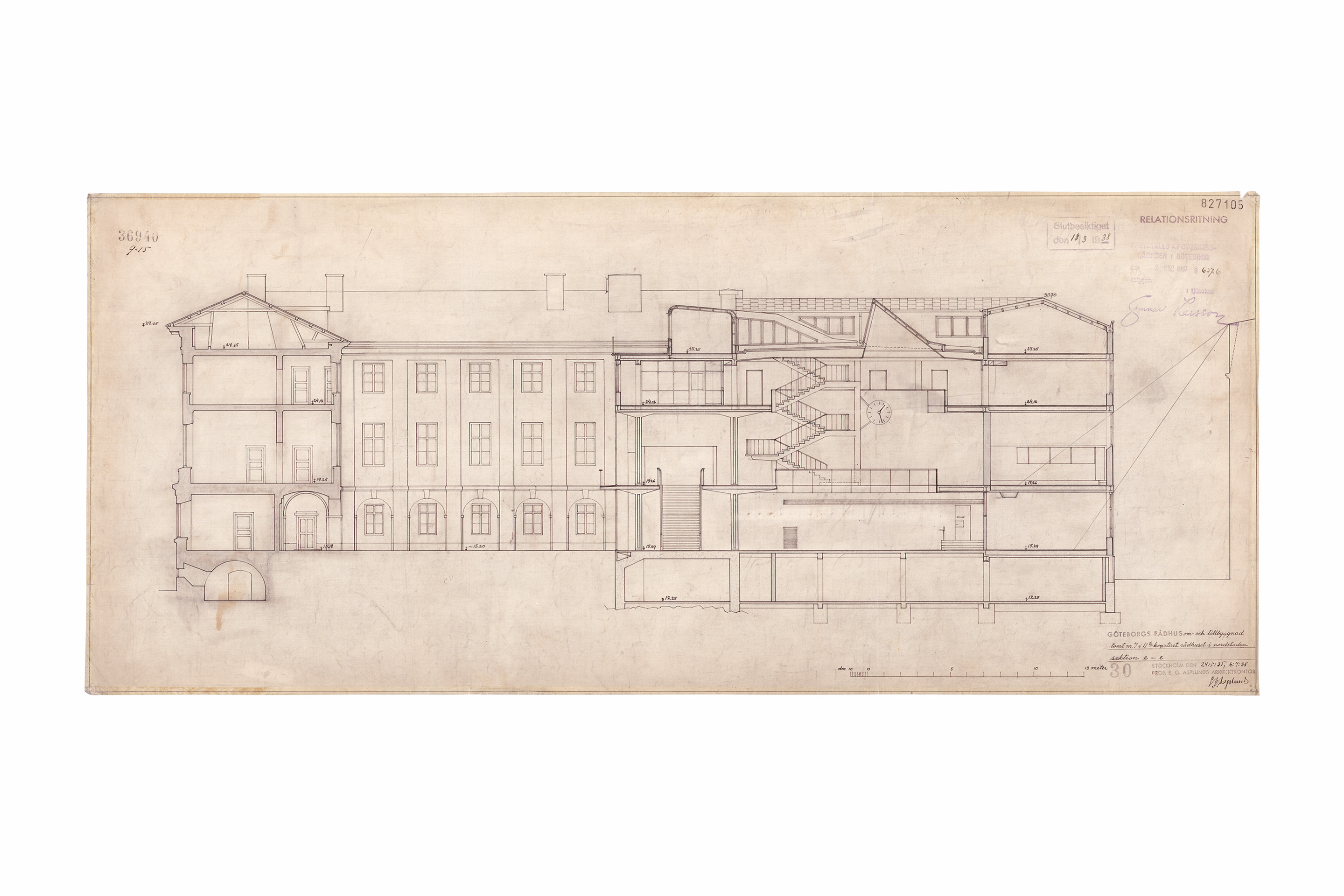

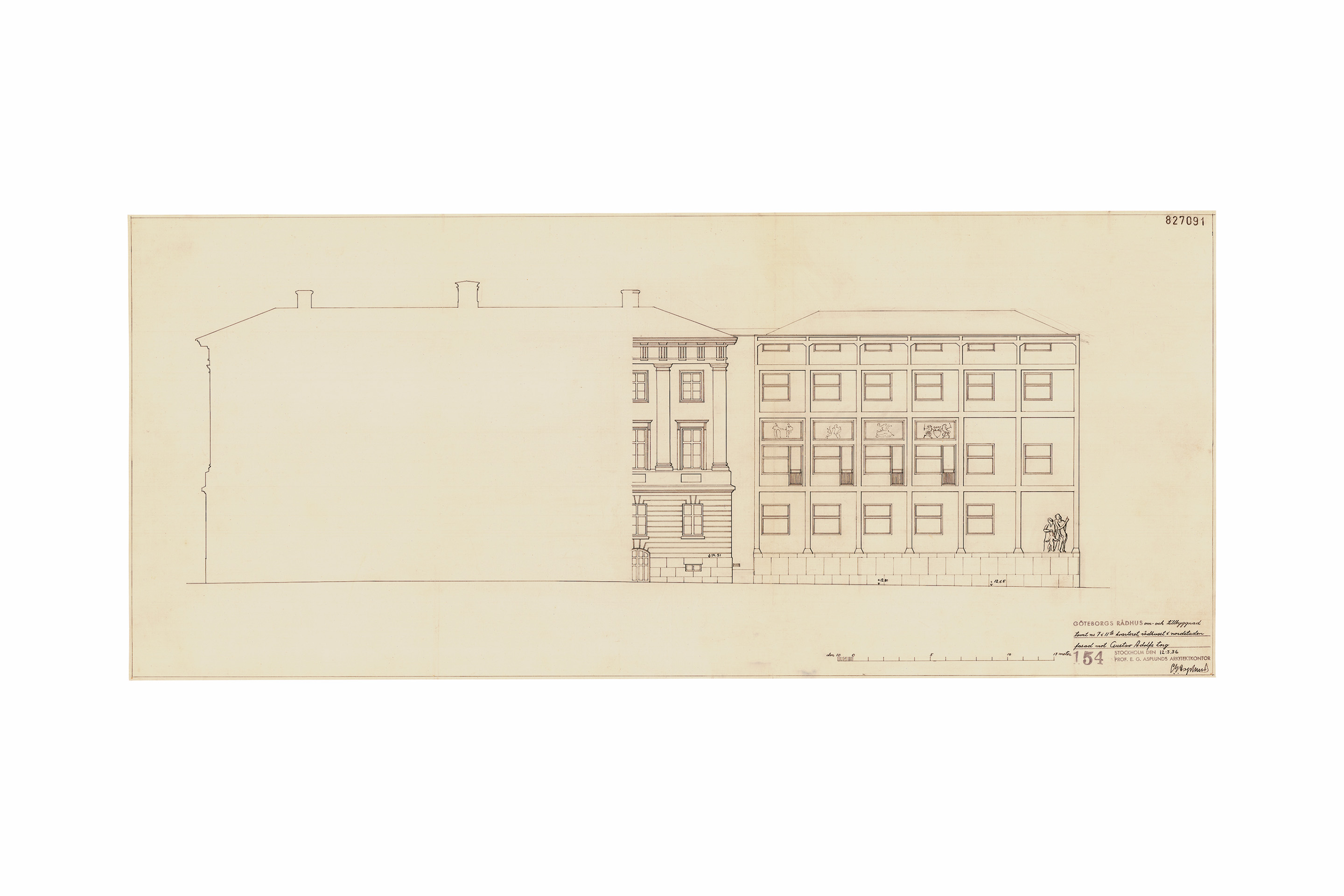

The solution, ultimately approved in 1935–36 following considerable hesitation, is a façade that clearly declares its status as an extension: no entrance, no autonomous centrality, a body set slightly back from Tessin’s building with a shallow impluvium marking the break between the two pitched roofs. The pilasters on the façade recall the classical lexicon in highly stylised form—base, shaft and capital reduced to signs—while at the same time expressing the building’s steel frame. The windows are not centred within their «compartments» but are laid out with a left alignment, as though magnetically attracted to the town hall, suggesting that the symbolic centre of gravity of the complex still lies in its historic part. Corresponding to one of the courtrooms on the second floor, «the four mezzanine windows that touch the old building are wider and more elaborate, creating a dissimilarity that destroys the inertia of a mere juxtaposition»,[14] transforming the grid into an almost entirely glazed screen. The attic is pierced by small rectangular openings that function as a modern frieze. Between 1937 and 1941, bas-reliefs by Eric Grate (1896–1983), The Four Winds (De fyra vindarna), were added around the larger openings, while the courtyard received Seated Girl (Sittande flicka) by Gerhard Henning (1880–1967).

In terms of its «vocabulary», the new volume is subordinate to the old—adopting its proportions, vertical rhythms and colours—yet it does so without resorting to literal imitation, preferring a patient «purification» of echoes and a cautious but definite shift towards a modern language instead.[15] Here «[…] Asplund performs a consciously ambivalent operation: he shows the steel structural grid exposed, but avoids rigidity and symmetry, scattering instead hints of a careful contextualisation. Although it is far from satisfactory from an aesthetic standpoint, the result rejects overly facile syntheses and prefers to entrust the extraordinary internal hall with the task of offering meaningful indications of an idea of modern space conceived in an elegant and welcoming way».[16] In this dialectic between continuity and variation, the façade seeks neither replication nor rupture: indeed, it constructs a controlled relation where modernity manifests itself in a measured way on the exterior, while unfolding fully in the interior spaces.

Asplund’s extension is one of the first modernist additions in direct contact with a historic building and became a model for many post-war European reconstructions.[17] The Rådhus is recognised as one of the earliest examples of a modern architecture grafted onto a historic context not by polemically interrupting it, but rather by reinforcing continuity with the «pre-existing structures».[18] The Göteborg Courthouse thus operates as a laboratory for a modernity that accepts the resistance of place and uses it to soften the abstract excesses of functionalism. Its strength does not lie in an isolated iconic gesture, but in consistency with which structure, façades and circulation are conceived as a single whole. The new wing is a compact block of three storeys plus attic, with a steel frame and concrete floors, plastered externally and lined internally in pale ash wood. In plan, old and new interlock like two pieces of a puzzle: a «tab» of the modern volume penetrates the original, creating a real continuity between the two buildings. Each of the four façades responds to a different role within the urban system. The one facing Gustaf Adolfs Torg is austere: monumental in scale, functionalist in grammar, harsh in the asymmetry of its windows. On the Köpmansgatan side the grid is compressed, the spacing between the pilasters narrows, and the openings shift in a tighter, almost industrial rhythm. On the backside, facing the Christinae kyrka, it becomes more uniform: the openings widen and the balconies turn into thin metal «lintels». The fourth façade—the most important in terms of spatial experience—does not face the city but the internal courtyard, where the wall dissolves into a large double-height curtain wall crowned by a masonry band with a succession of regular openings. This is the true «main façade» of the courthouse, the one through which the space of the new hall is revealed, a «covered square» that recalls the Blue Hall of Stockholm City Hall by Ragnar Östberg (1866–1945), Asplund’s mentor.

The route that leads towards the extension, is constructed as an almost theatrical sequence: one enters through the three doors at the top of the grand stair that lead into the seventeenth-century town hall atrium. A series of invisible signals, scattered throughout the building, guides the visitor inside; once inside, invites them to look up, where the space opens vertically: a large, full-height hall—paved in Ekeberg marble, the same used in the courtyard to blur the boundary between interior and exterior—is flooded with zenithal light from a long industrial rooflight that runs along the northern half of the ceiling from east to west. The interior of the extension is a space of extraordinary complexity, layered vertically by cantilevered galleries, lit by natural light filtering in both laterally and from above, and organised around a large panopticon void. In this interplay of routes and levels, the building acquires a Piranesian quality, with spaces that seem to extend beyond: walkways weave in and out, overlapping, apparently continuing beyond what is visible, opening towards uncertain directions.[19]

Two staircases structure the space and declare its character:[20] on the one hand, the large suspended stair, reminiscent of a ship’s gangway, blue painted on the «sottosquadra»—the underneath part of its surface—and supported by slender metal rods descending from above; on the other, the «staccato» stair—its design explicitly recalling the staccato notation on the musical stave—an angular, more intimate flight that gradually disappears into the light. On the first, the treads have low risers and generous goings; on the second, the steps have a complex, almost baroque articulation, obliging the visitor to slow their pace as they climb. The courthouse thus prescribes a specific «gait», an almost choreographed rhythm that calms the anxiety of those awaiting a verdict while at the same time introducing a certain gravitas: an awareness of being in the presence of the law.[21] Here, the modernisation of tradition[22] does not consist in erasing the solemn character of judicial space, but in translating it into human scale. The modernist elements are orchestrated like the details of a ship: the lift originally entirely glazed, later screened with timber panels to prevent prying eyes from lingering beneath the young ladies’ skirts; the large frameless clock suspended in the hall; the «trefoil» lamps that recall the scales of Justice. Asplund and his collaborators designed everything: furniture, panelling, handles, carpets, telephone booths for journalists, courtroom chairs with slight variations in height to emphasise the judge’s elevated role. Within this universe of details sits the signaturmattan designed by Elsa Gullberg (1886–1984), a ceremonial carpet gathering the initials of all those who contributed to the work. This is a unique instance in architectural history that demonstrates the importantance of each stakeholder for Asplund. The letters are arranged according to three categories: the clients with the judges’ gavel, the builders with the trowel, the designers with a watchful eye, showing Asplund’s irony in the inclusion of the initials of Göteborg’s two main newspapers, at the time particularly critical.

Although over the years the courthouse has undergone a series of changes in the exterior colour of its façade, the interior still reflects Asplund's original fil rouge:[23] the idea that, in a building where the individual encounters the State, the built form must bring people closer to the law not only through monumentality, but also through the measure, the calm and the clarity of space. It is in this interior, both soft and severe, that the project reaches its akmé: the courthouse becomes a secular temple of law, a place where the silence and the light translate a renewed idea of justice into architectural form.

References

[1] For a comprehensive history, see AA.VV., Tiden, Platsen, Arkitekturen. Asplunds Rådhus i Göteborg, Arkitekturmuseet, Stockholm 2010; N. Adams, Gunnar Asplund’s Gothenburg. The Transformation of Public Architecture in Interwar Europe, Penn State University Press, University Park 2014; C. Caldenby, Göteborgs rådhus / Gothenburg court house, Arkitektur, Stockholm 2015.

[2] See B. Zevi, Erik Gunnar Asplund, Il Balcone, Milan 1948, pp. 32–33; M. Capobianco, Asplund e il suo tempo, Tip. Licenziato, Naples 1959, pp. 18–22; N. Adams, Gunnar Asplund, Electa, Milan 2011, pp. 11–13; L. Ortelli, L’Adeguatezza di Asplund, LetteraVentidue, Syracuse 2018, pp. 67–75.

[3] Conversation between the author and Birgitta Martinius, curator of the exhibition.

[4] E. Lux (ed.), acceptera, LetteraVentidue, Syracuse 2024, p. XIII.

[5] See E. Lux (ed.) 2024, cit., pp. 149–184.

[6] See N. Adams 2014, cit., pp. 55–57.

[7] See N. Adams 2011, cit., p. 31; M. Landzelius, Dis(re)membering Spaces: Swedish Modernism in Law Courts Controversy, Göteborgs universitet, Göteborg 1999, p. 122.

[8] L. Benevolo, Storia dell’architettura moderna, Laterza, Bari 1960, p. 617.

[9] On the role of U. Åhrén, see N. Adams 2014, cit., pp. 106, 132, 140.

[10] On legal reforms in Sweden and the role of J. Thyrén and K. Schlyter, see N. Adams 2014, cit., pp. 107–122.

[11] See E. G. Asplund, Göteborgs rådhus om- och tillbyggnad 1935–1937, Rådhusbyggnadskommitté, Göteborg 1938, p. 32.

[12] Testimonies by Å. Porne and N. Rissén in N. Adams 2014, cit., pp. 58–64.

[13] See P. Blundell Jones, Erik Gunnar Asplund, Phaidon, London 2012, p. 173.

[14] B. Zevi 1948, cit., p. 33.

[15] See S. Ray, L’architettura moderna nei paesi scandinavi, Cappelli, Bologna 1965, p. 95.

[16] M. Biraghi, Storia dell’architettura contemporanea vol. 1, Einaudi, Turin 2008, p. 371.

[17] See L. Benevolo 1960, cit., pp. 617–618.

[18] See E. N. Rogers, Esperienza dell’architettura, Einaudi, Turin 1958, tav. 146.

[19] See S. Wrede, The Architecture of Erik Gunnar Asplund, The MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts 1980, p. 170.

[20] See G. E. Kidder Smith, Sweden Builds, The Architectural Press, London-New York 1950, pp. 184–186.

[21] On the theme of walking, see E. Lux (ed.) 2024, cit., pp. 150–152.

[22] See N. Adams 2014, cit., p. 92.

[23] See F. Alison (ed.), Erik Gunnar Asplund mobili e oggetti, Electa, Milan 1985, pp. 101–111. The restoration of the building was carried out by the studio Gajd arkitekter (2013–15).