Low environmental impact formula

The approach of a multidisciplinary cooperative

The construction sector can become regenerative: reducing mass, enhancing function, and extending the life of buildings and materials reduces emissions, supports local supply chains, and empowers communities. The 2401 cooperative shows how to design together for a positive impact.

Testo in italiano al seguente link

The construction sector today accounts for nearly 40% of global CO₂ emissions and around 50% of all raw material consumption. Among the possible levers for change, the choice and use of materials play a central role. Reducing the environmental impact of building requires activating every available potential for transformation. The diagram shown (fig. 1) illustrates this systemic approach: the environmental impact of a structure or building element depends on the chosen material, the way it is used and the duration of its life. This logic translates into three interdependent levers, expressed as fractions: impact/mass, mass/function and function/service life. Three fractions for thinking about design and addressing what matters most: matter, function and time.

It was in this spirit that the cooperative 2401 was founded in 2020, bringing together engineers, architects and specialists around a shared motivation: developing proposals with low environmental impact and high social value. This is only possible through a collective, interdisciplinary and committed practice. 2401 is not only an engineering office: it is a place of exchange and experimentation, where technical expertise is intertwined with a shared environmental and social responsibility.

In this article, members of the cooperative examine their professional practice through one of the three levers. Taken together, their reflections outline an approach to design within 2401 that is common yet diverse. Structural design occupies a particular place in this discussion, as it typically represents between 30% and 70% of a building’s embodied energy ‒ and also because two of the authors come from civil engineering. Yet these perspectives, enriched by the diversity of their methods, extend beyond disciplinary boundaries to question the project as a whole.

Elodie Simon: impact and mass

Over the past decade, significant progress has been made in reducing CO₂ emissions from the operational phase of buildings, largely thanks to developments in energy systems. However, at the scale of the entire life cycle, nearly 50% of a new building’s CO₂ emissions are released before it comes into operation.1

A building’s embodied energy therefore lies essentially in its structural conception ‒ in the phases of extraction, transformation and transport of materials. Designing a structure with a low environmental impact begins with a deliberate choice of the materials employed.

For this reason, knowledge of supply chains, along with a detailed understanding of the territorial issues linked to production, is essential to assess the environmental impact of a building as a whole. It is also important to recall that material choices often reflect global social inequalities: extraction and transformation largely occur in emerging countries of the southern hemisphere to satisfy a seemingly limitless Western demand. For instance, «Switzerland’s concrete consumption is the highest in Europe, at 1.4 m³ per person per year – twice the world average».2

Today, petrochemical-based materials remain the cheapest and thus the most widely used: reinforced concrete, concrete masonry, polystyrene insulation, mineral wool, PVC finishes, and others.

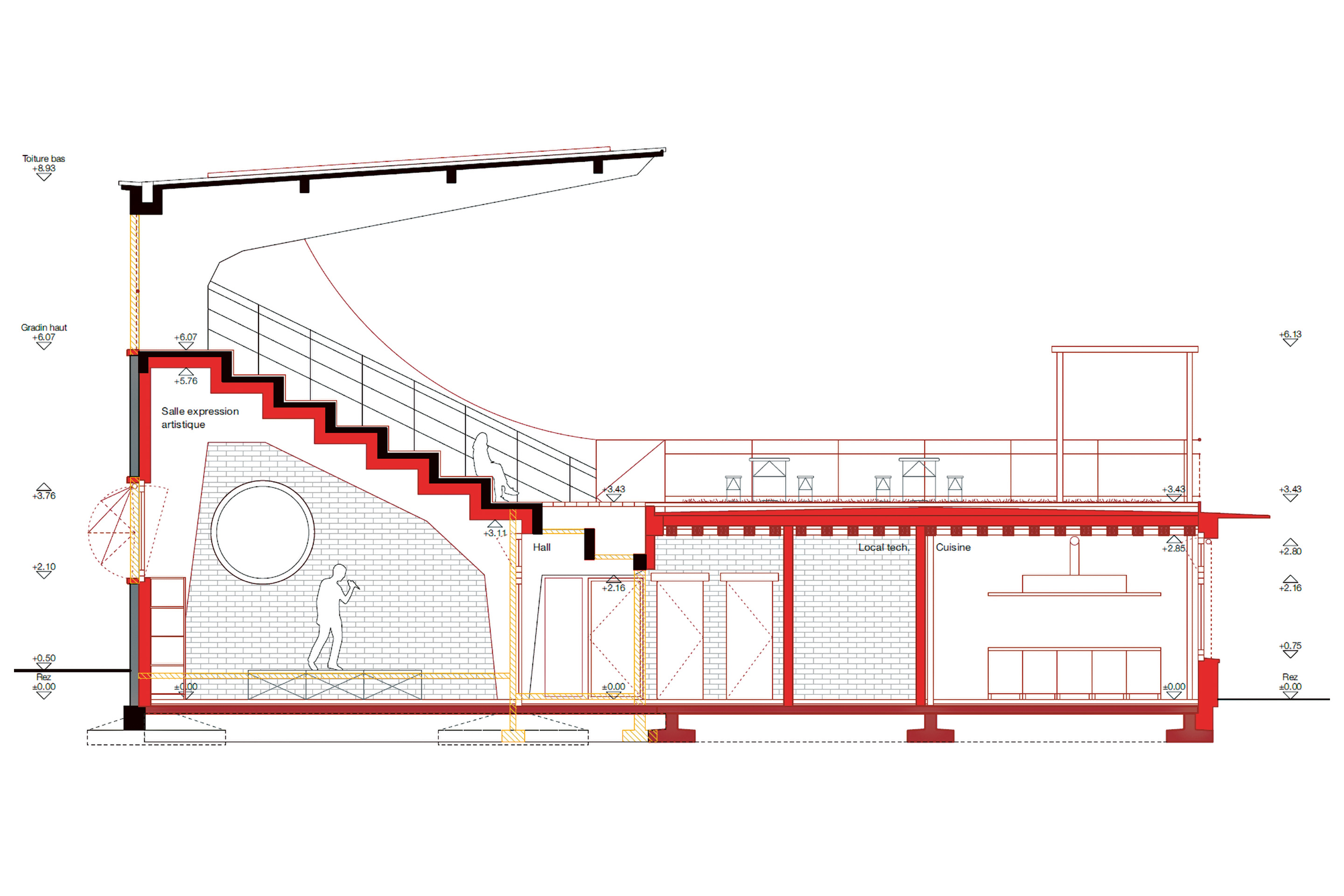

At 2401, instead of a monolithic or systematically composite approach, we aim for a reasoned diversity: selecting the most appropriate materials for the most appropriate use, avoiding complex assemblies that compromise the reversibility of the system. From the earliest stages of design, a «material performance specifications» helps define the functions and constraints of each structural element in order to assign the most suitable material. Finding the right material in the right place first means recognising and valuing the intrinsic qualities of each substance. 2401’s projects therefore prioritise reuse and bio-based or low-impact materials. The rebuiLT project is one example: the columns are made of recycled concrete, the frame is in timber and the walls are built in load-bearing straw coated in lime. But this approach can go further: existing buildings can often be preserved. The extension of the former Yverdon-les-Bains racecourse grandstands exemplifies this approach: the reinforced-concrete stands from 1930 were preserved and reactivated through the addition of a building, whose roof – shaped by the existing terraces – functions as a scenographic platform. The extension uses a steel structure and a roof made from reclaimed metal and timber, while the façades are carried out in timber framing insulated with wood fibre (fig. 2).

Each material finds its place according to its nature, its structural qualities and its impact. This approach requires continuous training and relentless curiosity: every material has its own history, footprint and potential, which must be understood in its context.

After material choice comes quantity: the mass of a structure is never neutral and plays a decisive role in its environmental footprint.

Julien Pathé: mass and function

The question of mass needs to be raised: our works have grown heavier; today we build with more material than we did in the past. Mass in itself is not the issue, yet greater mass entails a higher environmental impact, whether due to built volumes, transport, or excessive use of materials. Everything must be questioned, everything must be minimised. Mass is the common indicator of all our impacts; it must be taken seriously.

When founding the cooperative, we had considered calling it «minimal» to anchor, with a word almost akin to a manifesto, our attitude: minimising everything. But reducing our approach to a single term would have been … reductive. Not everything, in fact, can be minimised: certain values must be maximised. Such is the case, in particular, for the quality of what is built, which in the fraction (fig. 1) appears in the denominator through function. This duality is reflected in our statutes, which specify that members work to maximise social value while minimising environmental impact.

As for function ‒ the service provided by an element or a material ‒ it must be questioned throughout the entire project. Within a strategy focused on reducing impacts, nothing would be more absurd than conceiving a function for which no need exists. Returning to the fraction, the denominator would tend toward zero and, even with minimal mass, the ratio would become infinite. Necessary functions must therefore be identified and the others removed. This implies taking a step back and challenging established habits. Yet such distance is creative: understanding more clearly the functions of buildings, elements, and materials means understanding more clearly what we build and why. This stance nurtures dialogue among project actors and reinforces mutual understanding between disciplines. It is in this spirit of collaboration and exchange that we practise our profession within 2401. Take a wall: it may fulfil structural, aesthetic, acoustic, or thermal functions. And yet, depending on context, it does not necessarily need to meet all these requirements ‒ or it may need to meet different ones. To understand it fully, it must be considered in all its dimensions. The structural engineer cannot confine themselves to statics, the energy engineer cannot limit themselves to thermal behaviour, nor can the architect focus solely on form. Each must broaden their disciplinary scope so that it intersects with that of the others. It is within this common ground that the quality of what is built is forged, as an optimisation of functions.

As for mass ‒ i.e. quantities ‒ one certainty remains: to do better, we must do less. Every opportunity for reduction must be seized and, above all, we must stop looking for excuses not to act. We insist on this attitude because, despite how obvious the virtues of sobriety may be, excuses arise far too quickly in practice: «It’s not me, it’s the others!» «The others» are, by turns, consultants, clients, standards, budgets, or context.

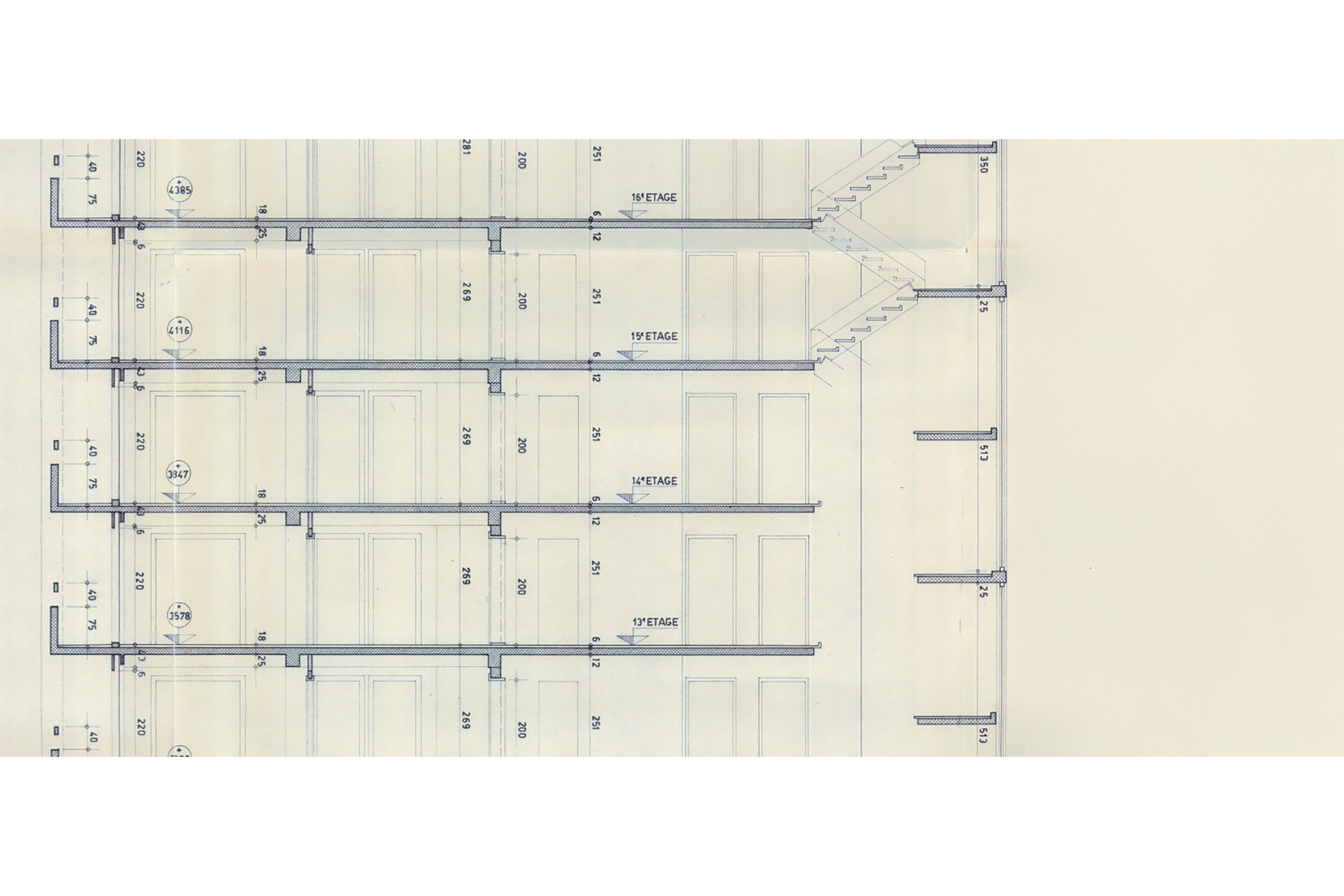

On site, in direct contact with the existing, the picture is clear: no major technological revolution has occurred in a century, and yet construction has grown heavier. Ancient works bear witness to a different constructive intelligence, in which each material was used sparingly and the goal was first and foremost to meet the function minimally. We are currently working on a 1960s tower with 12 cm slabs (figg. 3–4) ‒ nothing exceptional at the time ‒ or on a sports grandstand whose slabs are a now unimaginable 7 cm thick (fig. 2). By comparison, today’s residential slabs often measure 25–30 cm, and 40–50 cm are not uncommon in industrial, office, or public buildings. This is no longer feasible.

Sometimes it is not laziness that leads us astray, but the opposite: the cult of the gesture. If laziness makes structures heavier through convenience, the cult of the gesture drives disproportion, ostentation, and spectacle. Works become demonstrations of force: unnecessary cantilevers, gratuitous long spans, contradicted load paths, and so on. These constructions claim to be feats, but in turning their backs on rationality they forget function and sacrifice material on the altar of the designer’s ego. Our fraction then tends toward infinity. This is untenable in a finite world.

Elodie Vautrin: Function and Service Life

The amount of energy required to fulfil a function decreases the longer that function is ensured. Once the function has been evaluated, the durability of a building therefore relies on preserving what already exists, since the cleanest energy is still the one not consumed.

Within a circular logic, three levels of action can be distinguished: preserve, reuse, then recycle. At 2401 we apply this approach from the very first project phases. Thus, in the parallel study mandates for transforming the grandstand of the former racecourse in Yverdon-les-Bains (fig. 2), we worked with the architects to preserve and enhance the existing structure. In addition, the extension’s structure responds to programme requirements and is entirely conceived to be built from reused elements.

Far from being a new idea, reuse was long the norm before being marginalised by the industrial standardisation of the twentieth century. Today, in Switzerland, this practice is regaining momentum, supported by committed actors, emerging supply chains, and a gradual evolution of technical and regulatory frameworks. Despite certain obstacles ‒ logistical, regulatory, or insurance-related ‒ reuse brings numerous advantages: reducing embodied energy, limiting raw material extraction, decreasing waste, and supporting local industries. Focusing on load-bearing structures, the most common contemporary materials each offer specific strengths for structural reuse.

Concrete, for example, provides an intriguing field of experimentation: a reused element has already undergone shrinkage and creep cracking, and its mechanical strength increases over time. Its monolithic nature, often perceived as a constraint, becomes an asset: a slab can become a wall, with no formwork and no curing time. The deconstruction project of the industrial building Baumettes 21 in Renens (fig. 6) thus fed into four new construction projects.

Steel, thanks to its standardisation, naturally lends itself to reuse. Rolled profiles are easy to identify and their properties easy to verify. Reusing such elements quickly yields a positive environmental balance, while reducing the remelting required within the recycled-steel supply chain. We tested this in the extension of the «la Manufacture» school in Lausanne (fig. 5), where most of the structure is built from reused sections. Lastly, timber is seeing the formation of a dedicated supply chain thanks to new tools for traceability and characterisation. A living and adaptable material, it offers strong potential for direct reuse, especially when minimally processed and sourced locally.

Within the cooperative, this intention to prolong the service life of structures and materials is embedded in a collaborative and evolving organisation. Each project becomes a shared experience, in which material knowledge and structural design develop jointly, following a logic of collective learning and sustainable coherence. Yet a project’s coherence does not play out solely in walls or structure: it is also built in the way we work together. Technical durability cannot exist without human and organisational durability.

Acting Together for Low-Impact Construction

Sustainability cannot be decreed: it must be practised and built collectively. Within the 2401 Cooperative, technical approaches find their full meaning when supported by a committed group in which each competence serves the common good.

The cooperative operates according to principles of holacracy and shared governance: the organisation is structured into thematic circles, composed of roles that define responsibilities and duties toward the collective. Each member freely chooses their commitments and may take part in multiple projects or activities in parallel. This flexibility encourages agility, creativity, and ownership of decisions, allowing each person to advance within their specialty and experiment with new solutions.

Beyond materials and techniques, it is this collective dynamic that makes sustainability possible in the broadest sense: preserving resources, limiting ecological impact, transmitting know-how, and constructing buildings designed to last and evolve. Constructive sobriety and circularity are not merely technical goals, but the result of a collective intelligence and an organisation aware of the ties between matter, use, and time.

To think circular construction is first and foremost to think together: to share knowledge, experiment, reuse, reinvent, and allow the collective’s governance to sustain a sustainable and resilient vision.

Notes

1 Röck, «Embodied GHG emissions of buildings».

2 EMCO (European Ready-Mix Concrete Organization), 2016.

References

– Röck Martin, Marcella Ruschi Mendes Saade, Maria Balouktsi, Freja Nygaard Rasmussen, Harpa Birgisdottir, Rolf Frischknecht, Guillaume Habert, Thomas Lützkendorf, & Alexander Passer. «Embodied GHG emissions of buildings – The hidden challenge for effective climate change mitigation». Applied Energy (2019) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.114107